Sharie Holland received an unusual perk when she was hired as a seasonal ranger at Lake Havasu Park. Arizona State Parks and Trails put Holland up in one of the park's state-subsidized ranger housing units.

The Parks department usually reserves the units — with monthly payments of just over $60 at Lake Havasu — for managers, law enforcement officers, and rangers with special certifications. Holland was a temporary employee with no discernible parks experience.

Her new colleagues suspected special treatment. "We figured she knew someone in Phoenix,” one Lake Havasu staffer told Phoenix New Times.

Holland did know someone in Phoenix.

She knew Parks director Sue Black. And according to Shawn Schmidt, a longtime Black confidant, Holland knew the Parks director well. Schmidt said Holland on multiple occasions mentioned dating Black to him.

Schmidt also said he is "100 percent sure" with "no uncertainty" that Black confirmed a prior relationship with Holland during conversations in 2015, when Schmidt lived with Black in a house in Phoenix. During that time, Schmidt said, he socialized with Black and Holland on multiple occasions. Holland would hang out with them at the home Schmidt and Black rented near the Phoenix Mountains Preserve, as well as at nearby bars and restaurants, he said.

According to online records, Holland is associated with an address of a home Black owned in the 1990s.

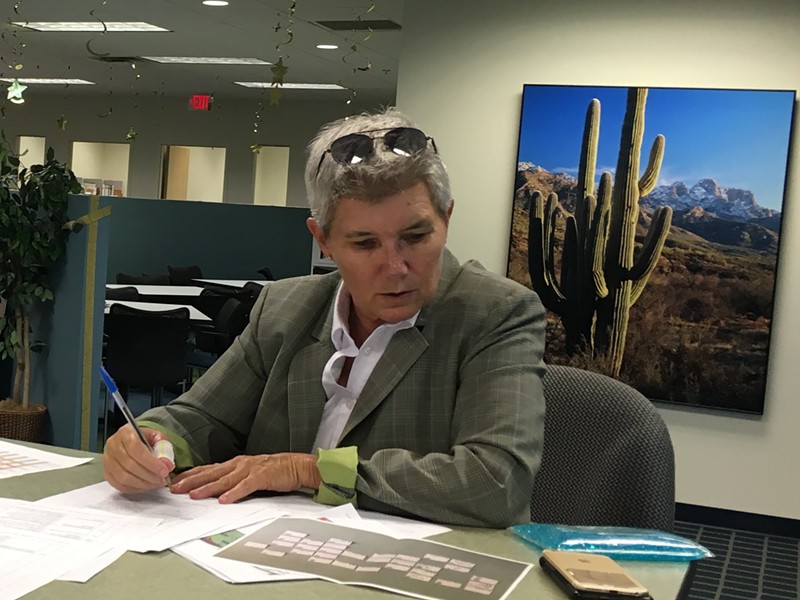

Schmidt has known Black since 2002, when the two worked together at Wisconsin State Parks. He later worked for Black as her executive assistant when she headed Milwaukee County Parks. In 2011, he left a job at Chicago Parks District after journalists raised questions about charges on his government credit card. (Schmidt, in a later interview, denied any wrongdoing regarding expenses — he said they were approved by his superiors.) Shortly after Governor Doug Ducey appointed Black as Parks director in 2015, she hired Schmidt as her personal assistant. Not long after he moved to Arizona, he was promoted to Chief of Operations.

Schmidt was terminated last year after he had a falling out with Black, he said. The stated cause for his firing was missing work. In an interview with New Times, he disputed the justification for his termination.

On Tuesday, October 2, New Times emailed a list of questions to the state Parks agency regarding Holland's hiring.

One day later, an official with the Arizona Department of Administration (ADOA) visited Lake Havasu State Park to question employees about Holland’s housing situation and an allegation that she smoked marijuana inside her state-provided residence. Holland was among the employees questioned. Three Parks employees, who asked to remain anonymous because they fear retaliation, confirmed details of the ADOA visit to New Times.

The site visit comes about a month after ADOA wrapped up a three-month investigation concerning Black’s treatment of employees. As Arizona Republic reporter Craig Harris has documented, the investigation was the third probe of Black's treatment of employees since she started three years ago. Black replaced Bryan Martyn, whose own embattled directorship included an allegation of nepotism — he hired his own three sons — that led to a two-week suspension.

An investigation by ADOA in 2015 found that numerous employees lodged complaints against Black, accusing her of regularly berating staff and asking staff to violate the Family Medical Leave Act. A March 2017 investigation of additional allegations found that Black had problems with "general management practices," but officials did not find any reason to discipline the director. ADOA launched a third investigation in July, taking up space in the office for three months and questioning dozens of employees about Black's treatment of employees.

Schmidt said he agreed to an on-the-record interview with New Times because he believes Black has headed a "toxic environment" in which she "torments people daily." He said Black should not be at the helm of the department.

"What do I have to gain from this? I am doing this because it is the right thing to do, and it scares me to death," he told New Times. "I’m doing it for the staff that are currently there. The longer she’s there, the worse it gets. The daily grind of being in that environment takes the toll on the staff."

New Times spoke with three former and five current Parks employees, including Holland, for this story.

On Monday, New Times visited Lake Havasu Park, a stretch of RV and tent campsites abutting the lake with a dock. The ranger housing area, a small plot with three unremarkable mobile homes, sits west of the campsites.

When approached at the doorway of her beige mobile home, Holland denied dating Black or even knowing the Parks director, her boss. "Call the HR department for the parks if you want to know anything," Holland said before shutting her door.

She was promoted to full-time ranger in March.

Black did not respond to multiple requests for comment, including a list of 19 questions emailed to her on October 8. New Times called Black on her cellphone with questions related to Holland last week. She said she would call back, but did not.

ADOA spokesperson Megan Rose declined to answer questions regarding the hiring of Holland, citing personnel rules.

Following the publication of this article, a spokesperson for Governor Ducey declined to comment, deferring questions to ADOA.

A former senior employee with a role in the hiring process said she felt uncomfortable with the way the department handled Holland's job application. The employee, who still works in government, asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation.

It became clear to her during a meeting with Parks deputy director James Keegan and a human resource employee that Holland was getting special treatment. Keegan reports directly to Black and, like Schmidt, worked with her closely in Wisconsin. The senior employee believed that the meeting's purpose was to discuss full-time positions.

At the time the senior employee worked for Parks, Black had asked for all full-time employee candidates to get screened through the department’s central office in Phoenix. That differed from the past practice of leaving hiring to individual park managers.

The hiring of seasonal employees, however, remained under the purview of park managers.

Nonetheless, Keegan spent most of the meeting telling the senior employee and human resource staffer to hire Holland for the seasonal Lake Havasu position. Keegan also asked the two staffers in the meeting to waive hiring requirements for Holland. He told the human resource employee to skip a background check and medical check, the senior employee said.

More than a month later, as part of an investigative memo of an allegation that Holland smoked marijuana in her mobile home, an assistant park manager at Lake Havasu raised concerns that Holland did not undergo a medical check. New Times has seen a copy of the memorandum.

During the meeting, Keegan also told the senior employee to grant Holland a space in ranger housing.

The senior employee objected, stating that there was no precedent for seasonal rangers getting housing at Lake Havasu. Managers, assistant managers, law enforcement officers, and employees with special certification (such as wastewater certification) typically get preference for housing because they are more likely to be needed outside work hours.

During the meeting with Keegan, the senior employee said Parks had already denied a full-time ranger a housing unit because she did not fit the department's criteria and that they were reserving vacancies for people with law enforcement experience. Giving Holland special treatment could erode trust, the employee said.

As she put it to New Times, "When you have a system and a process, and someone comes in and breaks it, it undermines everything we would do as a team."

Keegan did not care about the senior employee's objections, she said. He shook his head and said, “You need to make it happen,” according to the employee. He did not respond to multiple requests for comment, including a list of 19 questions emailed to him on October 8.

A copy of a ranger housing agreement obtained by New Times states, "Arizona State Parks provides on-site housing for employees in order to provide 24 hour monitoring for the health, safety and security of park visitors and the security of state property and park resources." The agreement makes explicit that the housing should not be provided "for the economic benefit of employees."

Former Parks deputy director Kelly Moffit, who worked for the department for 14 years, told New Times in an interview he could not recall an instance in which a seasonal employee received ranger housing. "In my experience, it would be highly unusual," he said. "That was not typically done.”

In an emailed statement, Parks spokesperson Thompson said Holland "underwent checks as required." Thompson added, "Any further information is confidential pursuant to state personnel rules."

The former senior employee told New Times she knew Holland and Black were acquainted, but did not know how they knew each other. She said Holland and Black showed up together to a bar for a work outing prior to Holland's hiring as a ranger. "It was very clear they had a relationship of some sort," she said.

Three Parks employee with knowledge of Holland's hiring corroborated with New Times that another full-time ranger asked for and was denied housing before Holland came on board. The state granted that ranger a mobile home after Holland received the key to hers.

Ranger housing at Lake Havasu runs between $50 and $62 per month, according to the Parks housing inventory. As of September 2018, the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Lake Havasu City is $596 per month.

Holland's mobile home included a washer and dryer purchased in fiscal year 2018, as well as a water heater purchased in fiscal year 2017, according to an internal 2018 Parks housing inventory obtained by New Times. By comparison, the washers and dryers in the other two mobile homes date back as recently as fiscal year 2011. The inventory does not list a water heater for either home.

Morale among staff at Lake Havasu Park suffered after Holland received housing, according employees.

"It rubbed everyone the wrong way," one staffer said. "It just wasn't fair. We realized it was 100 percent favoritism."

When an ADOA official visited Lake Havasu last Wednesday, he not only asked about Holland's housing situation, but also about the allegation that she smoked marijuana inside her state-provided mobile home, employees with knowledge of the investigation told New Times.

The official's questions referenced details in a report written by a park manager with a background in law enforcement. New Times has seen a copy of the memorandum, which was addressed to Parks Human Resources Manager Nicole Fleshman, and copied to Western Region Manager John Guthrie and former Lake Havasu State Park Manager Pete Knotts.

Lake Havasu State Park Assistant Manager Stephen Chruisciel, a certified law enforcement officer, wrote on June 24, 2017, that he had "reasonable suspicion" to believe Holland possessed and consumed marijuana on park property, in violation of state law and Parks policy. He described visiting Holland's mobile home the day before he wrote the memo to change an air filter.

Chrusciel wrote that, while he was changing the air filter, he smelt an odor consistent with marijuana. He confronted Holland, who was inside the residence at the time. She denied she smoked marijuana in the mobile home. Chrusciel wrote that he told his supervisor, Knotts, about the encounter. Knotts instructed him to continue investigating.

Chrusciel wrote that he interviewed another ranger, Jim Wilson, who reported that he smelled a "skunk weed" odor coming off of Holland on two separate occasions. During one of the occasions, Wilson told Chrusciel she had "bloodshot eyes and seemed untalkative and dazed."

After the initial encounter at the mobile home, Chrusciel and Knotts interviewed Holland a second time, according to the memo. During the interview, Holland declined to take a urinalysis test and suggested the smell might be a fragrant soap that she kept in her home.

Chrusciel told Holland that she was no longer permitted to drive any state-owned vehicle while they continued investigating the matter. The assistant manager requested that Holland undergo drug and medical screening.

The former senior employee who attended the meeting with Keegan about Holland's hiring said she also saw Chrusciel's report when it was sent.

The senior employee said that, upon learning of the allegation, she asked the regional manager covering Lake Havasu Park, John Guthrie, to check department policy to see whether Parks had authority to search the home for illicit substances.

Not long after, the senior employee said, Keegan contacted her about the alleged incident. "When he asked me what the situation was, I gave all the information I had at that point and said we were waiting to determine the next individual step. I asked if we could put the employee on leave without pay," the senior employee said.

According to the employee, Keegan responded, "Don’t worry. I’ll take care of it." She told New Times that she does not know how Parks handled the allegation after her contact with Keegan.

In response to questions related to the allegation that Holland used marijuana on park property, Parks spokesperson Thompson declined to comment, citing personnel rules.

Parks policy prohibits employees from working under the impairment of drugs or alcohol. In cases where there is reasonable suspicion that an employee may have been under the influence at work, supervisors may determine whether a suspected employee should undergo drug screening.

"Refusal to submit to such tests can subject the employee to disciplinary action up to and including dismissal," the policy states.

ADOA's visit to Lake Havasu Park to question employees on Wednesday comes after years of turmoil at the department, some of which has been documented by the Republic. Black has come under fire after staffers claimed that she got drunk at public events, used racial slurs, violated procurement practices, and other alleged wrongdoing that was the subject of multiple investigations. Most recently, Black's Parks department fired a longtime employee with eye cancer who had accepted protection under the Family and Medical Leave Act. Parks rehired that employee, Sue Hartin, after Governor Ducey came under fire on social media.

Black has weathered all the controversy during her tenure at the head of Arizona parks. Despite problems arising in 2015, she received a hefty raise in 2016, the Republic reported. Last year, the American Academy for Park and Recreation Administration awarded Arizona the Gold Medal for the best-managed parks system in the nation.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangleLeft",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangleRight",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangleLeft",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangleRight",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]