Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station is a desert colossus. The largest nuclear power plant in the U.S. is armed with three reactors that churn out 32 million megawatt-hours per year, providing power to millions of people from California to Texas.

It’s also just 50 miles west of Phoenix.

So when a report last week said that cyberattacks have targeted the information systems of companies that operate nuclear plants, it seemed certain that the nation's largest nuclear plant could be a target, too.

According to the New York Times, the only company that is a known target of the hacking attempts is the Wolf Creek Nuclear Operating Corporation, which operates a nuclear plant near Burlington, Kansas.

John Keely, a spokesperson for the Nuclear Energy Institute, said that his industry’s 99 nuclear plants, including Palo Verde, were unaffected by the cyberattack. Post-9/11 security measures and isolated computer systems at Palo Verde “ought to give Arizonans a lot of comfort,” he said.

“These sites are true islands of operation,” Keely told Phoenix New Times. “They are in no way connected to networks, or LAN, or even the Internet. Information does come out of them – performance factors, how much electricity they’re producing – but no information goes back in.”

This one-way road of information prevents a malicious hack of the variety that recently infiltrated the networks of Target and Home Depot, compromising customer data. Keely added that in the event of a breach, the companies that operate nuclear plants have to notify the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which then informs the public.

The Arizona Public Service electric company owns and operates Palo Verde, which is located near the town of Tonopah. Jill Hanks, a company spokesperson, emphasized a "comprehensive, multilayered program designed to defend the plant against cyberattacks."

"It’s important to understand that the computer systems that are used to operate the power plant are not connected to the Internet in any way," she told New Times. "Nothing from the outside can control equipment that is used to operate the plant."

Even so, the sheer size of Palo Verde could make it an attractive target for hackers who want to gain access to information or sow chaos within a nuclear plant’s systems.

Dave Lochbaum, a nuclear energy expert at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a policy group that advocates for tougher regulations on nuclear power, said hackers weigh ease of access and the potential value of intrusion when selecting a target.

“Nothing against either Iowa or Kansas, but those factors would tend to rank Palo Verde higher on the target list than the Duane Arnold nuclear plant in Iowa or the Wolf Creek nuclear plant in Kansas,” he wrote in an email to New Times.

“But the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission's approach to cybersecurity is to have all plants have protection up to their standards with the standards being uniform across the states," he added.

Experts say cyberattacks are a growing threat now that sprawling computer systems carry the work of government agencies and corporations. After the Stuxnet computer virus caused centrifuges used to enrich uranium in Iran to spin out of control, it’s a brave new world for adversaries hoping to disrupt nuclear technology.

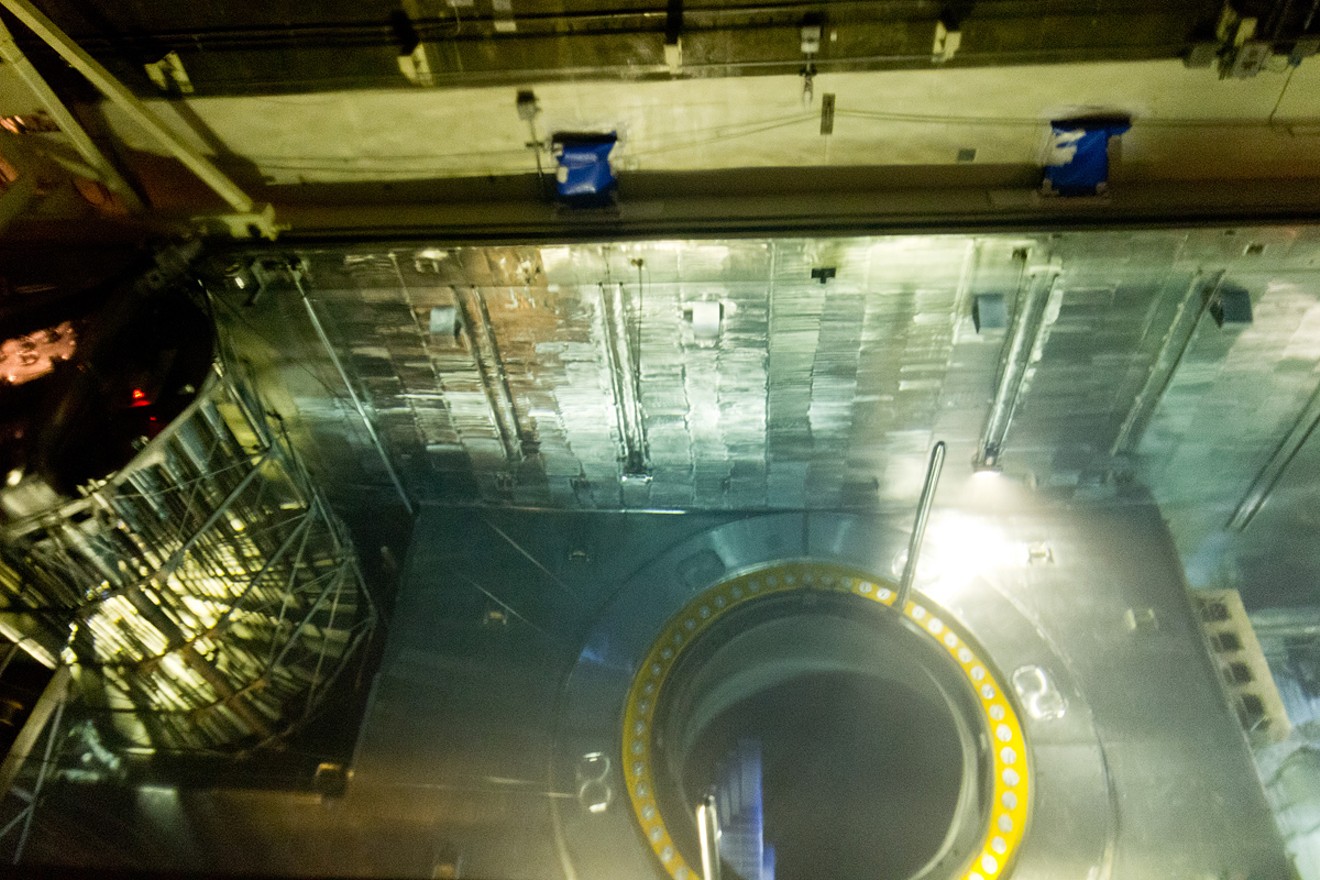

The reactor chamber at Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station during a refueling shutdown.

Tom Carlson

The administration has clearly taken notice. In May, President Trump signed an executive order, mostly in line with prior initiatives, that directs federal agencies to assess cybersecurity risks and to coordinate with the private sector. And on Tuesday, Energy Secretary Rick Perry said that "state-sponsored" hackers are a real and ongoing threat to nuclear energy facilities.

Federal regulators requires plant operators to maintain evacuation plans for the 10-mile radius around the facility in the event of a radiation leak. According to Bruce Monson, senior radiological planner for the Maricopa County Department of Emergency Management, the 10-mile radius around Palo Verde is home to approximately 8,869 people. Zoom out a little further, and millions of people in the Phoenix metro area live practically next door.

The room with the turbines where the steam produced by Palo Verde's reactor is converted into electricity.

Tom Carlson

“Right now, perhaps the biggest vulnerability nuclear plants face from hackers would be their getting information on plant designs (e.g., blueprints) and work schedules with which to conduct a physical attack,” Lochbaum said.

“Nuclear plants routinely take emergency systems out of service for testing and maintenance," he added. "If hackers obtained information about when a key component, like an emergency diesel generator, would be out of service, the list of equipment they'd need to sabotage to cause a bad outcome would be shortened, increasing their chances of success.”

As it happens, Palo Verde recently had a generator out of commission. In December 2016, a backup generator for one of Palo Verde’s reactors exploded during a routine test. And yet in a controversial decision by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the nuclear plant continued to operate without shutting down for 57 days.

According to internal memos obtained by the Arizona Republic, some agency employees criticized the decision, arguing that a loss of power could result in a radiation leak if the sole remaining generator failed. APS officials said it was safer to keep the reactor running to avoid a complicated shutdown procedure.

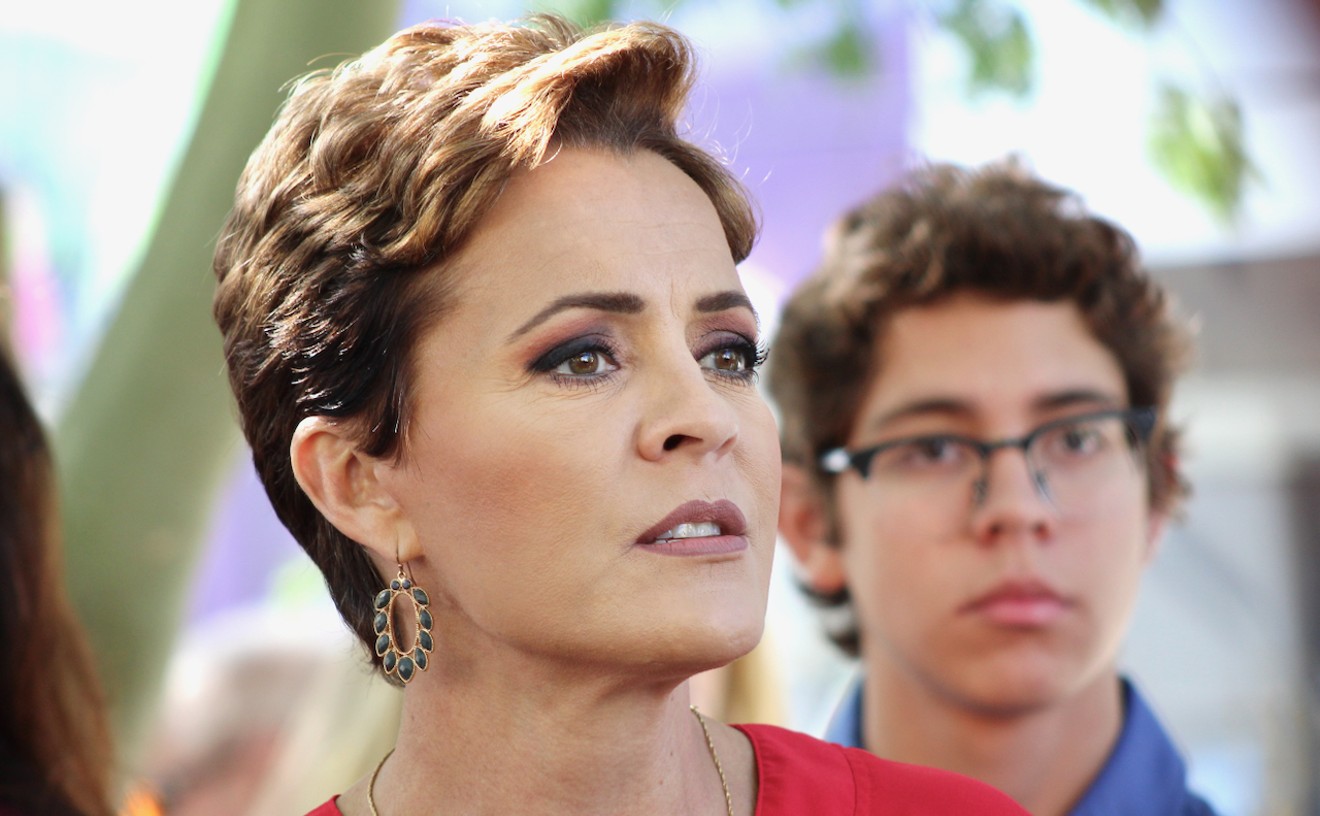

During refueling, spent fuel rods are moved into this area and new nuclear material is moved into the reactor chamber.

Tom Carlson

The plant’s three reactor licenses were renewed in 2011 and now expire beginning in 2045.

Questions of how to defend critical infrastructure aside, Palo Verde generates an enormous amount of clean energy – a not-insignificant thing for power-thirsty cities in the desert.

“That is a true flagship facility in our fleet and around the world,” Keely said. “And every Arizonan should be proud of what that plant does, not just for Arizona, but for the whole southwest.”