The story of killer Winnie Ruth Judd would shake the growing Arizona city and the whole nation. Judd’s story made front-page news nationwide, spawning crime fiction novels and journalistic recountings. Even humorous plays and puppet movies were created about the “Trunk Murderess.”

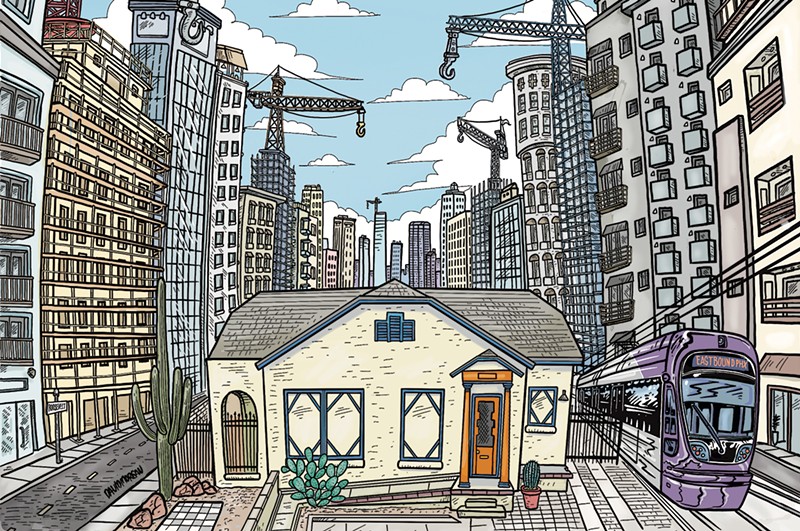

Decades later, the house — the only surviving witness to that saga — sits amid evidence of the city’s exponential growth. It’s a block from the Thomas Road and Central Avenue light rail station and surrounded by boxy modern condos, an office complex parking structure and a contemporary art gallery.

The fact that the structure remains at all is due to local bankruptcy attorney Robert Warnicke. Ten years ago, the Phoenix native purchased the dilapidated and weathered home to transform it into his law office. "I totally used the Winnie Ruth Judd story to save the house,” Warnicke explained, though he admits he “would have used any excuse” to do so.

As the vice president of the Phoenix Historic Neighborhood Coalition, Warnicke has worked to preserve more than one of Phoenix’s most infamous residences. He also owns a 1930s-built home in the historical La Hacienda subdivision down the street from the Judd house and has been active in keeping that locality vibrant and authentic.

La Hacienda is one of 36 neighborhoods designated by the city as residential historic districts. Many of these neighborhoods have experienced notable comebacks over the past decade, and city blocks that were once essentially ghost towns are now among the most popular places to live in Phoenix.

Since the early 20th century, when many of the houses in these neighborhoods were built, the city has seen tremendous growth. Almost 50,000 residents called the Valley home at the time of the trunk murders in 1931. By 1950, the city’s population had doubled in size. In 1980, Phoenix was one of the 10 most populous cities in the country. Now, with 1.6 million residents, it ranks as the fifth-largest in the U.S.

During that span, central Phoenix’s classic subdivisions have gone from thriving to neglected and back again. Arizona natives and transplants who once would have aimed for the suburbs are now drawn to the city’s old neighborhoods for their strong sense of community, older homes and proximity to downtown.

As demand for these hamlets has skyrocketed, the city has spent grant money and longtime residents have fought tooth and nail to preserve them.

"This was a place people were incentivized to live," Warnicke said. "There was a sense of belonging, a sense of we're together in this kind of thing."

As these neighborhoods continue to grow in popularity, he hopes they stay that way.

Robert Warnicke poses in front of his law office, which is also the home where Winnie Ruth Judd committed the infamous Trunk Murders.

Morgan Fischer

High demand

Buying a house in central Phoenix used to be relatively cheap. It isn’t anymore.In the late 1980s, Encanto-Palmcroft resident Jack Marks bought his single-story 1940s house for $225,000 — or about $560,000 in today’s dollars. Now, his home is estimated to be worth a staggering $1.26 million. A four-bedroom residence in the same neighborhood is listed at nearly $1.9 million today.

A smaller three-bedroom home in Coronado — a historic neighborhood a mile east of Encanto-Palmcroft — is selling for $720,000, nearly three times its value from 2021. In Ashland Place, a tiny historic community off Central Avenue between Thomas and McDowell roads, a three-bedroom house valued at about $333,000 just three years ago is now going for nearly $950,000.

With more new residents willing to shell out that kind of money to be in the city’s center, longtime residents could make a small fortune by selling. But the same things that draw new people to these neighborhoods keep the old ones there. Joyce Grossman purchased her Encanto-Palmcroft home in 1995 for $259,000 and could sell it today for around $1 million. She has no intention of doing so.

“It’s like an old-fashioned neighborhood,” Grossman said. “You know your neighbors.”

She’s hardly alone. James Judge, a 10-year resident of Ashland Place, doesn’t plan on leaving Midtown, where his husband can walk to work at his pediatric physical therapy clinic. Coronado resident Donna Reiner feels her neighborhood is “like a small town” — so small that the 77-year-old ditched her car seven years ago. She’s now known for walking around Coronado with her red-white-and-blue golf umbrella to grab take-out Thai food, enjoy a soda at MacAlpine’s Diner or catch the city bus.

When she leaves her house for good, she said, it’ll be “in a body bag.”

Newer residents have picked up on the same vibe. Lauren Armour moved to Encanto-Palmcroft with her husband four and a half years ago, drawn in by the neighborhood’s history and walkability. “We went on a bike ride through Encanto-Palmcroft, and he was like ‘This is it,’” the 34-year-old Armour said. “I never thought something like this could be in Phoenix.” Armour is now raising a 3-year-old son and 9-month-old daughter in the neighborhood. Like so many others, she’s fallen for its charm.

“People are just really proud of living here,” Armour said. “We’re never without projects going on in the neighborhood with somebody’s exterior.”

Residents love that small-town feel in these historic areas, and they want to keep it that way as new people like Armour flood in. Encanto-Palmcroft hosts “monthly schmoozes” during which time residents gather to drink, chat and bond on a neighbor’s front lawn, Grossman said. The neighborhood doesn’t have a homeowner’s association, and residents don’t pay dues, yet there is a kid’s club, holiday light contests, home tours and even a monthly printed magazine.

But preserving these communities — much less revitalizing them — takes more than neighborly spirit. In 2015, the Phoenix City Council adopted a 10-year plan that laid out financial incentives for the preservation of historic homes, including several grants and a hefty property tax reduction of 35%-45% through the state’s historic property tax program. The city is also in the public outreach stage of updating its historical preservation plan, which will be approved by the city council in 2025.

In addition, Phoenix’s Exterior Rehabilitation Assistance program supports residents who “sensitively rehabilitate the exteriors” of their historic homes while “promoting reinvestment in Phoenix's historic neighborhoods.” The program reimburses owners for 50% of the cost of home projects, with a maximum reimbursement of $20,000. The city’s low-income historic housing rehabilitation program also funds projects of up to $30,000 for those who meet its requirements.

As historic neighborhoods like Encanto-Palmcroft become more popular for homebuyers, longtime residents work hard to prevent neighborhoods from losing their defining characteristics.

Morgan Fischer

A delicate balance

Warnicke’s Phoenix Historic Neighborhood Coalition is one of many nonprofits doing this work as well, and longtime residents also have taken preservation matters into their own hands.Some protested in city council meetings against the building of large modern apartment complexes. Warnicke demonstrated against the establishment of a project near his home in La Hacienda that would have demolished a long-standing low-income housing development and transformed it into a 15-story high-rise residential tower.

Others have purchased historical houses to prevent them from being bulldozed, while some take on revitalization projects to bring dilapidated historic homes back to their former glory. That’s what Judge does, albeit for a profit as a designer and realtor. While some call what he does “house flipping,” Judge prefers the term “home curation.”

The difference, he explained, is he’s “dedicated to listening to the soul of the house and embracing the soul.” Judge eschews transforming historical house with modern or trendy designs. Instead, he tries to “keep as many historic original elements as possible while balancing the need for modern amenities and modern conveniences” — for example, carving out space for a dishwasher but keeping a home's original cabinets.

The comeback of these neighborhoods isn’t an entirely positive development, though. High home prices and disappearing rental properties have pushed some long-term low-income families out. Cars from nearby developments park in communities such as Encanto-Palmcroft, overwhelming residential streets. Unregulated Airbnbs and short-term rentals have flooded neighborhoods and caused disturbances.

“It’s a struggle,” Warnicke said. “Not only are you having to basically fight the city and fight the developers, but you have people that don't understand how important houses are — the history of the houses — who just want to live downtown because it's a place to live.”

Bad flip jobs also have damaged old properties. Victims of bad remodels are everywhere, Judge said. “People have no business in flipping historic homes unless they appreciate and understand historic homes,” he said. He believes he has such an appreciation. But while he “hopes people don’t think I ruin” classic homes, he acknowledged that “some people probably think” he does.

And sometimes, there’s only so much a dedicated collective of neighbors can do. Even past wins can turn into losses. The Wrexler, which used to be a low-income apartment complex when Warnicke saved it from being demolished, is now marketed as a modern apartment complex with rent for a 630-square-foot one-bedroom unit going for almost $1,300 a month.

Mostly, though, the come-up for these old Phoenix neighborhoods has been a happy development. Residents remember how it used to be. When Warnicke was growing up in the area now known as Willo, downtown was “a ghost town after 6 o’clock.” Going out to dinner, Marks recalls, meant going to another part of town.

Grossman recalls being asked, “Why are you downtown?” after she first moved to Encanto-Palmcroft — the implication being that “it’s not safe.” Her answer to the question hasn’t changed that much over the years.

"When the weather's good, you see families out walking,” she said. “People greet you.”

It’s that way still, and she hopes it never changes.