Nowhere is that more evident than on the Navajo Nation, which on Thursday confirmed it had 405 cases in Arizona, out of 558 across the entire reservation, which spans portions of Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. That means that the Nation is home to 1.4 percent of Arizona's population but now has slightly more than 13 percent of the state's current COVID-19 cases.

Twenty-two people have died on the Nation, where an evangelical church rally in Chilchinbeto on March 7 is believed to be a source of the outbreak. At the end of March, the Navajo Nation implemented a curfew, from 8 p.m. to 5 a.m., in an effort to stop the spread. Acknowledging the severity of the pandemic for the Navajo Nation, Arizona Governor Doug Ducey on Thursday called the COVID-19 crisis on the Navajo Nation "top of my mind."

State and county data also show that the heavy coronavirus toll on the Nation makes the toll in each of the northern Arizona counties it spans — Coconino, Navajo, and Apache — also disproportionate to their populations.

Just over 143,000 people live in Coconino County, which stretches over 18,600 square miles of northern Arizona. The county is home to less than 2 percent of the state's population, yet it currently comprises nearly 14 percent of the state's deaths from COVID-19, the illness caused by the new coronavirus.

As of Friday, Coconino County data showed that of its 206 cases, 61 percent are in tribal communities. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 27.6 percent of people Coconino County identify as American Indian.

The remaining cases are in Flagstaff (20 percent), Page (18 percent), or other cities (1 percent). Nearly half of cases are people 55 years and older.

The county is not publishing a breakdown of data on the locations of deaths out of concern that people could be identified, county epidemiologist Matthew Maurer said during a press call on Thursday, although that could change as the cases and deaths rise in number.

Figures from the two other northern counties that overlap with the Navajo Nation similarly show the concentration of cases.

Just under 1 percent of Arizonans live in Apache County, in the northeast corner of the state. Yet 1.8 percent of the state's COVID-19 cases and 3.2 percent of deaths from the virus are there.

"Right now, all of our positive cases in Apache County have been on the Navajo Nation," county health department Director Preston Raban told Phoenix New Times. "All of our deaths have been on the Navajo Nation."

Areas of the county outside of the reservation have no positive cases so far, Raban said, adding, “Nothing yet has gone south of I-40 in our county.”

Navajo County, the band of nearly 10,000 square miles between Apache and Coconino County, has 1.5 percent of Arizona's population and 7.5 percent of its COVID-19 deaths.

The county doesn't publish a detailed breakdown of cases or deaths, but Brian Layton, the assistant county manager, said most of them are on the Navajo Nation.

“We have seen some cases here, off tribal land, but not nearly as many” as on the Nation, Layton told New Times.

A voicemail and email to a spokesperson for the Navajo Nation were not returned.

So far, the COVID-19 pandemic has drawn attention to metropolitan areas, where the absolute numbers of cases are "eye-popping," said Dr. Dan Derksen, the director of the Arizona Center for Rural Health at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Maricopa County, for example, had 1,741 cases of COVID-19 as of Friday — nearly 56 percent of cases in the state. But it is also home to nearly 4.5 million people, or just under 62 percent of the state's population, meaning that the proportion of the state's cases is lower than its proportion of the state's population.

In Arizona's vast, sparsely populated areas, including on reservations, not only do people have less access to medical care than their rural counterparts, but they also tend to have risk factors that heighten their risk of being hospitalized and put on a ventilator — or dying — because of COVID-19, Derksen said.

"There tend to be more low-income elderly who live in rural areas," Derksen said. And those elderly tend to have underlying conditions, such as asthma, emphysema, diabetes, or high blood pressure, that make them more prone to the ravages of COVID-19.

Lack of running water also presents challenges with hand-washing to prevent spread of the virus.

The only other county as disproportionately affected by COVID-19 is Pima County, which is home to 14.3 percent of the population but has nearly 28 percent of its COVID-19 deaths.

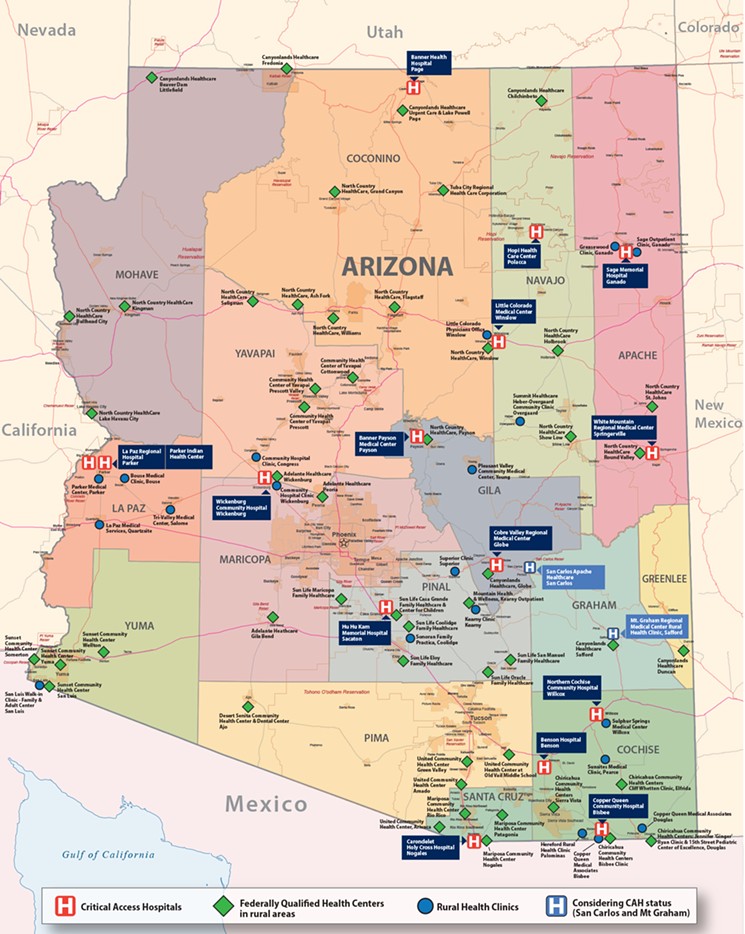

If people in rural areas can reach them — if they have working cars, if the road is good enough — Arizona has 15 critical access hospitals, which are designated by the federal government for having a maximum of 25 beds and being at least 35 miles away from other health care facilities.

The map below, courtesy of the University of Arizona, shows just how few and far between those health care facilities are:

In rural counties, hospitals and health clinics are few and far between.

Paul Akmajian/University of Arizona

Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez told the New York Times this week that the Nation is still waiting for emergency funds from the $40 million allotted to American Indian and Alaska Native communities from the coronavirus aid package that Congress passed in early March.

"We're barely getting bits and pieces," he said.

Coral Evans, the mayor of Flagstaff, which is in Coconino County, raised questions about how the state was distributing its allotment of resources from the Strategic National Stockpile to counties — whether it was by population, or by the impact of COVID-19.

If the latter, then the state's hardest-hit areas aren't getting resources like protective equipment and test kits proportionate to their need.

According to Layton, the assistant county manager for Navajo County, the first shipment of resources from the national stockpile was based on population.

A spokesperson for the governor's office did not respond to questions from New Times for this piece.