"I felt I was in a car wreck or something," Icedo, 28, told Phoenix New Times during a series of phone calls from Towers Jail, where he was most recently incarcerated. (He has since been released.) "My headache was super constant. There was no way it'd go away."

Jail staff didn't test Icedo for two weeks after he first reported symptoms, he said. The test came back positive for the novel coronavirus.

The events that happened after he first started feeling sick, as related by Icedo, are a harrowing glimpse into the unsafe conditions inside Maricopa County jails amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, and how local jails are handling it.

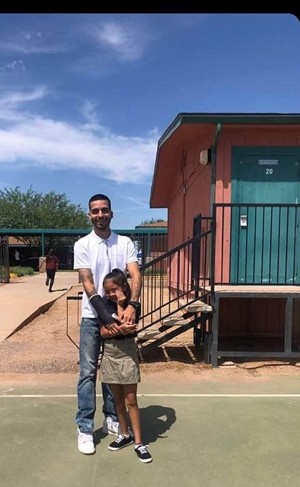

Icedo wasn't in jail for anything serious: He was convicted last year after he pleaded guilty to felony drug possession after an officer found marijuana wax on him during a traffic stop in 2018. With a few prior convictions on his record, including theft and possession of marijuana for sale, a judge slapped Icedo with a nine-month sentence for the substance, which is legal for adults in several states.

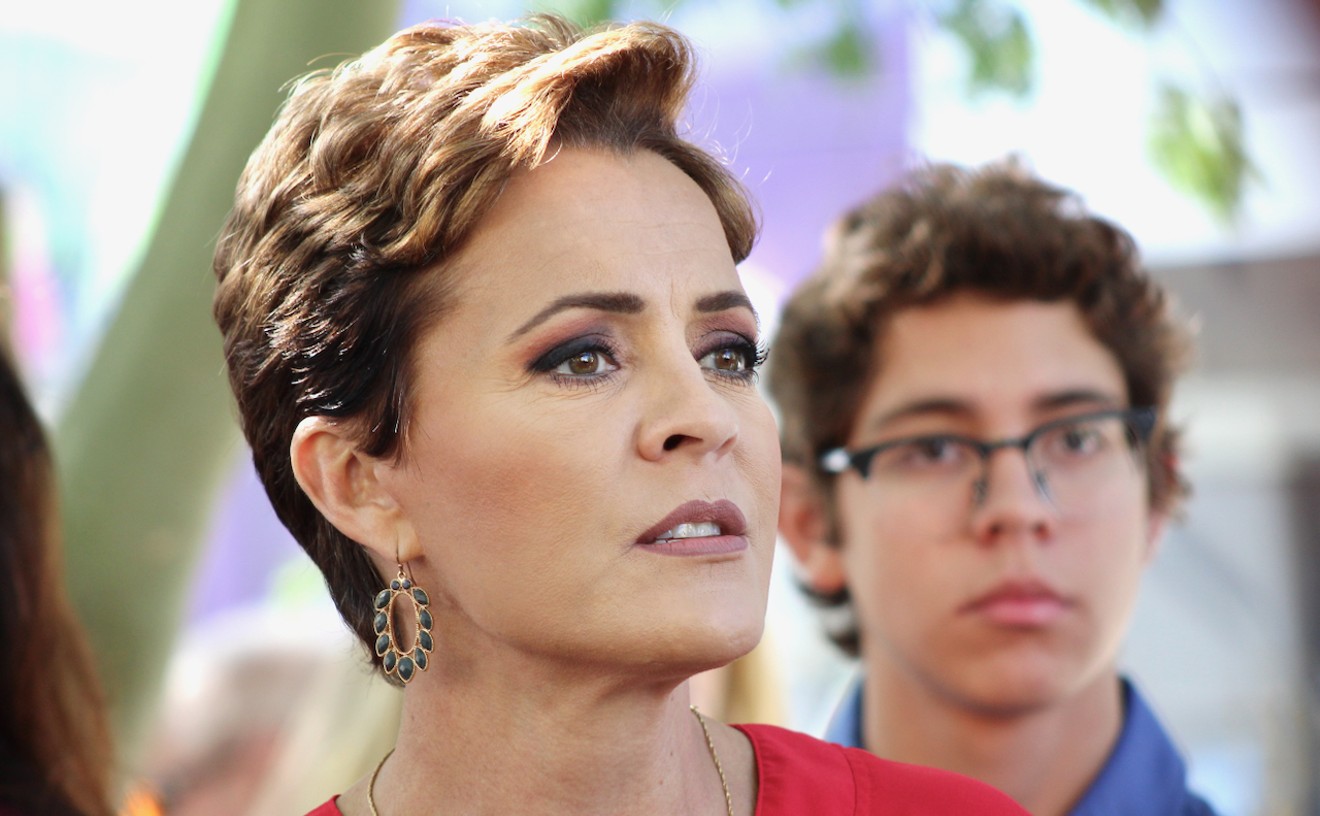

Icedo's account aligns with allegations made in a class-action lawsuit filed last month by the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona against Maricopa County and Sheriff Paul Penzone, alleging that jail staff members are failing to property test inmates for COVID-19, protect inmates who are vulnerable to the disease, ensure proper social distancing inside the facilities, or provide sufficient sanitation supplies and personal protective equipment. In interviews with Phoenix New Times, Maricopa County jail employees backed up the veracity of the ACLU's allegations and criticized the Sheriff's Office for a haphazard response to the pandemic.

As of July 8, 939 inmates out of the estimated 4,500 people in Maricopa County's five-jail system have tested positive for COVID-19, and there are 278 active cases in custody, according to county data. This is a significant surge from early June, when around 200 total inmates had tested positive. In less than two weeks, the number of COVID-19 cases in the jails jumped from six to 313, according to the ACLU lawsuit.

"I would say 90 percent of it was very accurate," said a long-time correctional officer at the 4th Avenue Jail in downtown Phoenix, referencing the lawsuit. (The officer requested anonymity out of fear of retaliation from his employer.) "A lot of what the CDC is recommending, we’re not following it. It’s kind of 'come in to work and make up stuff as we go.'"

In an email to New Times, Sheriff's Office spokeswoman Norma Gutierrez-Deorta declined to comment on the ACLU lawsuit and how it might relate to with Icedo's experience, citing "pending litigation."

"We will not comment on hearsay," she said.

Test and Isolation

When Icedo was housed at Durango Jail and starting to feel sick roughly a month ago, he asked for help and submitted a formal written request for medical attention. A nurse finally took his temperature and gave him ibuprofen, but that was it. He wasn't tested for COVID-19, and he remained in his crowded pod, where he and dozens of other inmates slept side-by-side in bunks and shared limited sinks, toilets, and drinking fountains in an open-air setting. (Correctional officers had previously started handing out masks to inmates, but the guards themselves weren't wearing them at the time, Icedo said.)He was moved to another facility, Saguaro Jail, where he continued to feel ill. Icedo said that he was pressured to work in the facility's kitchen by correctional officers, despite the fact that he informed them that he felt sick. He still hadn't been tested.

"I tried to get the day excused because I was sick, and the officers there, I don't know if they thought that I was lying or something, but they were threatening me with moving me or writing me up," Icedo said.

Eventually, it appeared that jail staff started to show interest in people who were reporting a wider variety of symptoms. Icedo said that several medical staffers came in to his pod and started asking inmates about their symptoms. He was then transferred yet again, this time to the 4th Avenue Jail, where he was tested for COVID-19 and quarantined in a cell with a elderly man who was exhibiting symptoms. In Icedo's telling, it was a miserable experience. They were locked down in a small, dirty cell for around 10 days, and were only allowed to leave to shower after seven days. Icedo was provided a toothbrush, but no toothpaste. He also said that he got an infection in his foot during his time in quarantine, which he attributed to how dirty the shower was when he was allowed to use it.

"It was literally a week from when I got there without no shower. No hour out, nothing," he said. "It was just straight lockdown. They wouldn't let us go out for nothing."

"I asked the sergeant ... 'Hey, I haven't showered in like four days, when am I going to be able to shower?'" he said. "He was like 'Oh, it takes up to a week.'"

In response to questions about the shower situation, Gutierrez-Deorta wrote that shower frequency for quarantined inmates is determined by "the amount of inmates in the unit, the 14 hours available daily for this activity (which is meant to avoid nighttime sleep disruptions of all inmates in the unit), cleaning of shower areas, necessary officer performed functions and the level of medical care each symptomatic/asymptomatic Covid inmate in the unit is receiving."

According to Olga Akselrod, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU who is working on the lawsuit against the county, Icedo's experience was far from unique.

"We have spoken with a number of people who reported symptoms consistent with COVID to jail staff and they were essentially ignored or just not tested," she said. "Part of what was happening is a very limited set of symptoms that the jails were considering to be indicative of COVID. So whereas the CDC lists many symptoms that are consistent with COVID, fever, chills, stomach issues, cough, the jail appears to have really been focusing very much on fever."

Ron Coleman, a spokesman for Maricopa County, declined to comment on Icedo's case specifically. But he wrote in an email that Correctional Health Services, the agency that provides medical services in county jails, "currently" tests inmates who have a fever of 100.4 degrees, respiratory symptoms, or have had close contact with a confirmed COVID-19 patient. They also screen for symptoms like muscle pain and sore throat. The current testing criteria have been in place since mid-May.

"Correctional Health Services’ testing protocol follows public health guidance: test those who are symptomatic and/or have had close contact with another person who has tested positive for COVID-19," Coleman wrote. "This approach, we believe, is the best way to accurately identify inmates who are infected."

"When a patient submits a Health Needs Request, they are evaluated promptly and, if indicated, placed in Medical Observation, treated, and tested for COVID-19," he added.

Coleman did not respond to questions about whether the agency's testing criteria has changed over time.

Once someone tests positive for COVID-19 or are "suspected" of having the virus, medical isolation is the norm.

"Everyone who has gone into isolation has told us they feel like they’ve been punished for seeking medical help," Akselrod said. "They basically feel like they’re in the hole."

"Their property is taken away from them, they’re placed into dirty cells that are not cleaned in any way, let alone disinfected," she said. "They’re on 24-hour lockdown with the exception of that minimal time that they’re given to shower."

Safety's Not First

While in quarantine, Icedo and his cellmate played an anxious waiting game as they waited for the test results. Icedo recalled expressing concern to a health care worker that if he was infected, he could infect his cellmate, or vice-versa."She was like 'No, you guys should be good'," he said. "They didn't really know, but we were still housed together."

Later, Icedo was told that he had tested positive.

"It's pretty crazy," he said. "I would have never thought that I would have caught it."

On the outside, Icedo's family, who stayed in touch with him through electronic messages and phone calls, was distraught about his test result.

"I was just confident that it was going to be negative," said Priscilla Icedo, Alexis' 27-year-old sister. "I trusted that the facility he was in was more than responsible and cautious and careful. I was really trusting that they wouldn’t allow that to happen."

In interviews with New Times, correctional officers described a chaotic and poorly managed response to COVID-19 inside jail facilities. There's a lack of uniform COVID-19 practices and protocols across the county's jails, poor communication between supervisors and guards, and a lack of personal protective equipment, they said. Meanwhile, many guards are calling in sick with COVID-19-like symptoms, adding more work for the staff who show up.

"Some jails initially were requiring face mask usage and then other jails were not," said Benjamin Fisk, president of the Maricopa County Sheriff Law Enforcement Association. "It’s just really been a piecemeal type of thing... People don’t know which pods are sick, people don’t know which pods are under quarantine. It changes on a daily and sometimes hourly basis."

Concerns over the lack of sufficient personal protective equipment, particularly at 4th Avenue Jail, are widespread. In a June 14 memo of concern filed internally at the jail and obtained by New Times, a guard at 4th Avenue Jail described a shortage of protective equipment in jail pods designated as "quarantine pods" and supervisors who were indifferent to the issue and his concerns.

"I asked them [supervisors] why is it that only some of the quarantine pods have the correct PPE equipment and some do not. They could not provide me with any kind of answer," the memo states. "MCSO is not providing a safe working environment for me and is endangering the health of everyone, by not providing us with the CDC recommended PPE to carry out our job functions."

"There does seem to be a disconnect from what is available within the Sheriff’s Office and what is being utilized," Fisk said. "Some facilities allow officers to utilize PPE gear pretty liberally for when they need to use it, other facilities are extremely strict on PPE usage and limiting how it is distributed."

Don't Ask, Don't Tell

In the days leading up to his release today, Icedo was housed in a pod at Towers Jail with other inmates in a less-restrictive quarantine. It's better there, he said, because he could shower regularly, access his personal property, and wasn't cooped up in his cell. But after other inmates heard about what happened to Icedo and others who were symptomatic, they were reluctant to report their symptoms and risk getting quarantined with little-to-no showers, he said."There's still people that are sick," Icedo said. "I'm pretty sure that they don't want to tell the nurses or the officers because they'll get put right back into quarantine where they won't be able to have any property, any hygiene, any meals or commissary items, [or] something good to eat, because the food that they give us here is horrible.""Everyone who has gone into isolation has told us they feel like they’ve been punished for seeking medical help," she said. "They basically feel like they’re in the hole."

tweet this

To advocates like Akselrod at the ACLU, this dynamic is especially detrimental to controlling the spread of COVID-19 inside county jail facilities.

"People are really hesitant to report symptoms to the jail staff because they are afraid of being put into the hole," she said. "You are really setting yourself up to miss a lot of COVID-19 positive cases because people are afraid to report them."

Icedo has left the jail, but there's no getting away from the pandemic. His mother tested positive for COVID-19 back in June, and now some of his siblings who live with her are symptomatic as well, he said. After being turned away from several severely overwhelmed drive-through testing sites in Phoenix, the family still doesn't know for sure who actually has contracted the virus. He doesn't think he'll be able to bring his daughter home anytime soon.

"My younger sister, she's like 16 right now, she's showing symptoms. She's having body aches, headaches, a lot of coughing," Icedo told New Times before he was released on July 9. "It definitely sucks. It's not good."