Then he paused, and something of a smile came across his face. “But GCU don’t like them,” he said.

Grand Canyon University has a tense relationship with Palmer, his cows, and his four rental properties, which are located on two acres along Colter Street in the center of the for-profit Christian university’s west Phoenix campus. On hot days, the smell of manure wafts over GCU’s manicured lawns and stately lecture halls. Sometimes, students try to scale the fences to get a better look at the small herd.

Palmer’s property is at the center of an ongoing court battle. In April 2022, GCU sued Palmer in an attempt to wrest control of the property away from him and put it in the hands of the courts. The case has dragged on for close to a year.

But Palmer is clear: He's not going anywhere.

Palmer is one of a dwindling number of GCU’s neighbors who have not sold their property to the school. Over the last decade, GCU has aggressively bought land around its campus, converting old apartment buildings into student housing and empty lots into athletic fields. The changes have been welcomed by some — but called displacement by others, as low-income communities and longtime residents are uprooted by GCU’s ambitions.

The university said its lawsuit is about safety. "The complaint has everything to do with ensuring the safety of the GCU community and nothing to do with our discussions with Mr. Palmer about the possible availability of his property," university spokesperson Bob Romantic wrote in an email to Phoenix New Times. Attorneys for the university pointed to “recurring and virtually unchecked criminal activity” that has flourished in recent years on Palmer’s land, and which posed “a grave risk” to students.

"Nothing in the complaint would give GCU any rights to that property," Romantic continued.

Palmer, though, is adamant that the lawsuit is nothing more than a land grab. “It’s our belief that they’re trying to bully him into selling the property,” said Jordan Greenman, a land-use attorney representing Palmer. “Which is what they tried to do many times in the past — and failed.”

The ‘Cow Guy’

To many of the 24,000 students who take classes on GCU’s campus, Palmer is known simply as “Cow Guy” — an enigmatic and at times threatening figure. “The view of Gail is that he’s crazy, dangerous, stubborn,” said Andrea Barrios, a film production student at the university. Students whisper that Palmer was offered millions of dollars for his land and refused to sell and that he chases trespassers away with a gun, she said. A thriving ecosystem of TikTok videos documents the “swamp cows" of GCU and their mysterious owner.Yet in person, Palmer is less curmudgeonly than you might imagine from an elderly landlord fighting with a powerful neighbor. He has a wry sense of humor, and laughed often at GCU’s distaste of his property. He is deeply Christian, a quality he does not find in GCU. “Those kids,” he said of the students. “Their moms and dads think they’re going to a Christian organization. But they’re a bunch of crooks.”

Palmer spoke to New Times in January, sitting in the empty living room of one of his duplexes along Colter Street. The place was being remodeled for new tenants. It was one of the first days of the spring semester, and the street — which visitors access after stopping at a GCU-staffed guard shack — was flooded with students. As Palmer looked on, a group of five people on skateboards grabbed each other’s hands and fanned out across the street like a daisy chain. “Look at this,” he said, shaking his head.

As Palmer spoke, he spread a large map across the floor: a bird’s-eye view of the neighborhood. On it, he traced the contours of GCU’s domain, which stretches west to east from 35th Avenue to Interstate 17, between Camelback Road and Missouri Avenue. From here, Palmer pointed to the center of the campus along Colter Street to a small rectangular lot — his own property with the cows and the rentals.

It was, he said, “right at the center of the bullseye.”

Palmer grew up on this piece of land, although now he lives nearby. His family moved to the lot in 1949, when he was 10 years old. His father, a welder, set up a workshop on the land. It wasn’t until two years later, in 1951, that GCU moved into the 90-acre lot next door. Palmer was there first.

Once, much of the land that is now GCU’s campus looked like Palmer’s property today — small farm properties with livestock and a house or two in the front. “This was way out in the country, way, way out,” Palmer said.

The city eventually reached it. So did GCU.

Aided by skyrocketing online enrollment, GCU has embarked on an “aggressive” spree of real estate purchases over the last 10 years. “As far as I’m concerned, they want to own Camelback to Missouri, 35th Avenue to I-17,” said Shirley Dieckman, the volunteer leader of the Alhambra Neighborhood Association, who has lived just south of GCU’s campus for more than 40 years.

“And they’ve pretty much bought it all. Except for Gail," she added.

Other holdouts do remain: Colter Commons, an affordable housing apartment complex mostly for seniors, and Kingdom Hall of Jehovah's Witnesses are two of the closest remaining neighbors. The university's relationship with the church and the apartments has been peaceful — unlike its relationship with Palmer. "Unfortunately, this particular neighbor has not been as friendly as others in our neighborhood," Romantic, the university spokesperson, wrote in reference to Palmer. "If someone does not wish to sell their property, our intent is to be a good neighbor and embrace them within the GCU community."

And many neighbors have appreciated some of the changes brought by GCU’s investment. Dieckman is among them. She values GCU's partnership with Habitat for Humanity, for instance. But she opposed the school's ultimately unsuccessful effort to annex a neighborhood park in 2017. "They did some wonderful things for everyone, painted a lot of houses, cleaned up a lot of yards," she said. "But that doesn't mean we owe our life to them."

The university's investment in the neighborhood has made it difficult to oppose them in court, attorney Timothy La Sota said. He worked with Palmer on an unsuccessful lawsuit in 2015 that challenged GCU's plans to take over Colter Street, which had been a public road since 1926. Taking over the road was a "special inside baseball deal," La Sota said. Yet, he said, "that part of town is considered better than it was before GCU."

Grand Canyon University argued that it was the city of Phoenix's right to give the school control over the road, and the Arizona Court of Appeals ultimately agreed.

The university has also faced backlash over the growth of its campus. In April 2022, around the same time that it sued Palmer, the university delivered an unexpected eviction notice to dozens of residents of Periwinkle Mobile Home Park. GCU gave them six months — and no compensation — to leave their longtime homes. Most residents had not realized that GCU owned the property, which the university bought in 2016. Over the last 10 months, Periwinkle residents have protested and won some concessions from GCU, including an extended move out deadline and money for furniture.

But the Periwinkle residents, like Palmer, want to stay. "We're asking to keep our homes," said Alondra Ruiz Vazquez, who has lived in the mobile home park for nine years. "We’re not asking for money or furniture or whatever else they thought we’d be happy with."

“It’s a bad part of town, there’s lots of crime, all of that,” Palmer admitted. “But poor people have to have a place to live."

‘Plagued by Crime’

Grand Canyon University’s current case against Palmer revolves around Palmer's four rental units. The university's attorneys argue that the units are “plagued by crime” and neglected by their aging landlord. The suit asked for a judge to place Palmer's property under the control of a court-appointed receiver.In the suit, attorneys outlined a variety of issues on the property, including several arrests over the last three years. In April 2021, the Phoenix Police Department searched one of the rental units and found "a significant quantity" of unspecified illegal drugs. The following May, the U.S. Marshals Service searched the property for a fugitive who was a friend of one of Palmer's tenants. The wanted person was arrested. The tenant had "previously threatened to strike an individual he believed to be one of [GCU's] students with what appeared to be a metal baseball bat," according to GCU attorneys

"It would have been irresponsible on our part if we had not taken some action on behalf of our students and employees to protect their safety," Romantic said.

The lawsuit also alleges that in May 2022, Palmer complained to a GCU security guard that three students jumped the fence to his property and that he "told two different security guards that he would shoot the minors." GCU said they were in fact 13- and 14-year-old schoolchildren who "simply wanted to see the cows being kept on [Palmer's] property."

These instances were hardly the first time Palmer clashed with GCU security. In April 2017, Palmer was arrested and charged with assault after a university police officer found him sawing through a wrought iron fence. Palmer was trying to access his irrigation lines that ran through GCU’s campus and which he had asked the school not to fence off, he said.

Court documents about the incident allege that when officers approached Palmer and asked him to stop cutting into the fence, he “cursed” at officers and refused, then “pushed an officer in the chest with his right hand … and turned toward the officer with the saw, which was still running in his left hand.”

Palmer doesn’t deny cutting the fence but scoffs at the idea that he assaulted the cop. “I saw [the officer] charge at me,” he recalled. “And I remember so vividly that I didn’t want to drop my new saw because I didn’t want it to break.” Palmer said he held the saw to the side, and the officer ran into his other arm. Then, two officers “slammed me on the hood of his truck and handcuffed me,” Palmer said, leaving him with an injury to his elbow that still nags him.

Although the Maricopa County Attorney's Office pursued the case for two years, prosecutors ultimately dropped the charges against Palmer without explaining the decision.

GCU's latest arguments against Palmer also have run into some trouble in court. At a July hearing, Palmer's attorneys showed he had evicted tenants shortly after the May 2021 and April 2022 arrests. A Phoenix police officer who worked with Palmer testified that the issues on his property improved in recent months.

"The dorms next door to Mr. Palmer's property have many more times the amount of [police] calls," Greenman, Palmer's attorney, told New Times. "Cops get called all the time. It's a busy area." That made it more difficult to prove that Palmer's property was a particular problem, he said.

In July, Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Rodrick Coffey sided with Palmer and refused GCU's request for a court-appointed receiver to oversee Palmer's property.

"Defendant demonstrated that he took steps to address problematic tenants once he became aware of their involvement in criminal activity," Coffey wrote in his opinion. "The Court does not find that the few incidents relied upon by Plaintiffs demonstrate that the Property is 'regularly used in the commission of a crime.'"

GCU has not given up the lawsuit, dragging it into settlement hearings and a potential trial. A settlement conference is scheduled for April 11. "It's our opinion that they're trying to cause a headache," Greenman said. "They're trying to push him to be so annoyed that he sells the property."

The university disagreed. "The lawsuit was filed for the sole purpose of ensuring the safety and welfare of GCU’s students, faculty and staff, which is of the utmost importance," Romantic said.

Palmer isn't swayed. "I tell my daughters, if you sell it to GCU, I'll come back and haunt you," he said.

‘Woe on GCU’

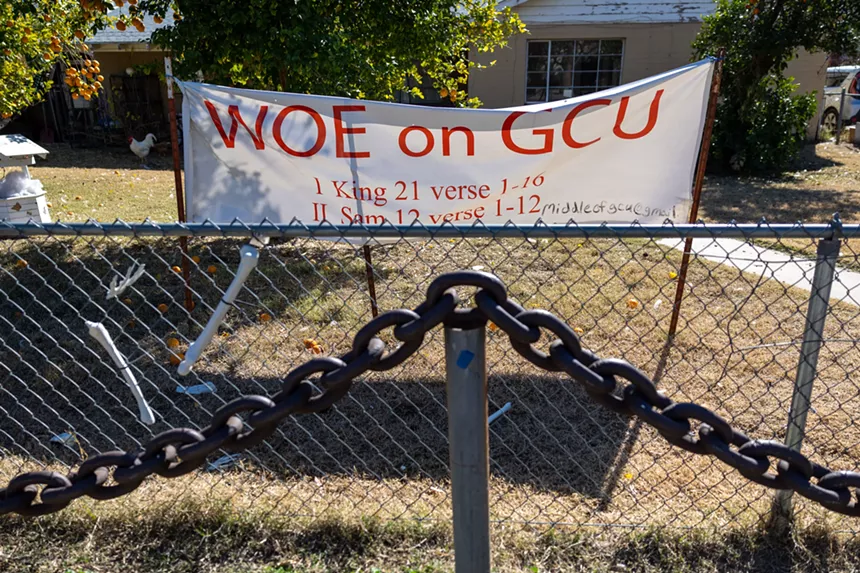

Banners displayed on Palmer's property proclaim in bold red type, “Woe on GCU.” The signs caused quite a commotion among the student body and on TikTok when Palmer strung them up.Underneath "Woe on GCU" is a reference to a Bible verse: 1 Kings 21:1-16. The passage is a short fable about a king that asks a humble man for his vineyard, offering money for the land, or even a better vineyard elsewhere. But the man declines, telling the king that “the Lord forbid that I should give you the inheritance of my ancestors.”

When the man refuses, the king orchestrates his execution.

Palmer, like the man in the Bible verse, is holding on to his inheritance, too. But he also has other goals for the land. When GCU approached Palmer and offered to buy his property, he countered. "I said I want $6 million for my place, and I'm going to keep $2 million for me and my family — that's about what the real market value would be — and I said I’m going to donate the other $4 million for homeless people and drug rehab," he said.

The university said that Palmer requested far more money. "Mr. Palmer’s latest ask in exchange for his two-acre property was $21 million plus a nearby half-acre property that GCU owns," Romantic wrote. "That, of course, is not realistic."

Palmer said he also wants to develop the land to provide transitional housing for low-income veterans. He has been working with John Mendibles, a lobbyist and executive director of the League of Veterans. Mendibles, a former Superior mayor with fraud convictions, told New Times that the lawsuit and a pot of funding that got tied up in the state legislature has stalled those plans.

"He is determined that he is going to put in low-rent housing for veterans," said Dieckman, Palmer's longtime neighbor. But she understood GCU's frustration with Palmer and the property, which she remembered had always been "a little rough."

"I told him, they've made their mistakes," she said. "But so have you."

For now, the property sits as it has for decades. Behind his rentals, back by his father's old welding shop and the cow pasture, debris has collected over the years — rusting hubcaps and rotting furniture, an old motorboat, scrap metal, and the belongings of a wheelchair-bound man Palmer met in a grocery store parking lot who lived for a time in a vehicle on his property. Weathered pecan trees are full of fruit.

"Us kids used to go out and pick them. We'd dry them out and bag 'em up. My dad bought both of us a red wagon, and we'd go out into the subdivisions with a wagon full of pecans," Palmer said. Nowadays, though, the pecans are scattered on the ground with the rest of his things.

"Nobody even picks them anymore. They go to Walmart," he said, grabbing one and cracking it in his hands. "We're too prosperous of a country, you know."