Arizona’s Board of Executive Clemency decided unanimously Thursday to deny a petition by condemned murderer Clarence Dixon to commute his death sentence

The board convened in the morning in a small boardroom in Phoenix to consider Dixon's case and reached its decision after listening to hours of testimony. In the afternoon the clemency panel decided it would not recommend that Governor Doug Ducey reprieve or commute Dixon’s sentence. It means the matter will not go to the governor's desk and that Dixon took one giant step closer to his execution, scheduled for May 11.

Dixon is sentenced to death for the murder of Deana Bowdoin, a 21-year-old ASU student who was strangled and stabbed to death in 1978. The board’s chair, Mina Méndez, said she had no doubt of Dixon’s guilt, and that he had failed to demonstrate “any remorse or acceptance of responsibility” for the crime.

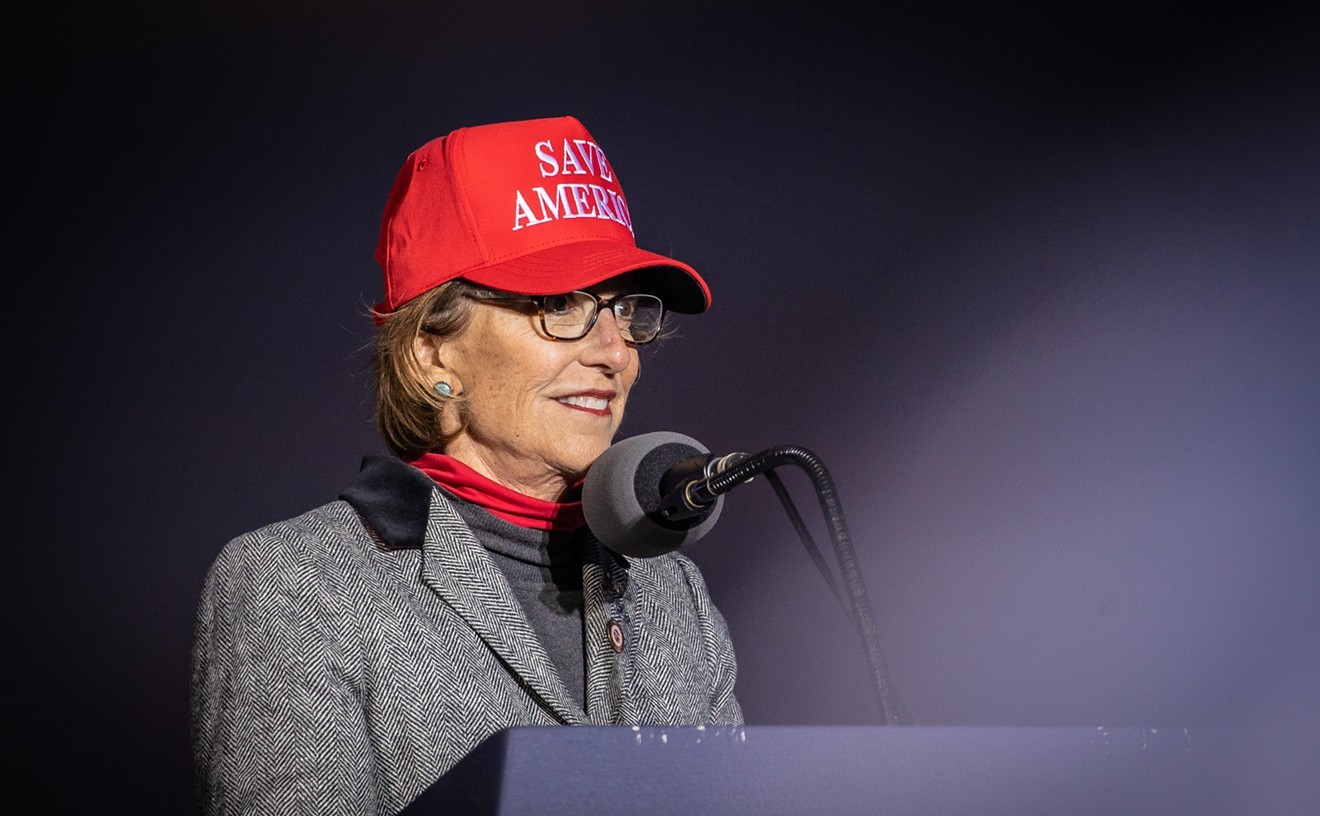

Many of Bowdoin's surviving family members, including her sister, had urged the board not to commute Dixon's sentence. "There is not one legal, social, or moral imperative for recommending reprieve or commutation," Bowdoin's older sister, Leslie James, told the board.

The hearing presented a thorough sense of the contours of Dixon’s case. Attorneys for the state and for Dixon made their case for and against his death. One of the main points of contention was the extent and the impact of Dixon’s mental illness, which his counsel argued should disqualify him from the death penalty.

Also at the center were the institutional failures at the heart of Dixon's case: In January 1978, Dixon was found to be insane and a potential danger to society by a Maricopa County Superior Court judge. He was directed to be committed to a hospital for treatment. Instead, he was released without supervision. Two days later, he killed Bowdoin.

For decades, the crime was left unsolved. It was not until 2001 that DNA evidence linked Dixon, Bowdoin’s neighbor at the time, to her death. He was convicted in 2008. Bowdoin’s sister, Leslie Bowdoin James, was 23 when she was killed. She’s now in her late sixties. Their parents have since died, without seeing justice carried out in their lifetimes.

Should Dixon’s execution go forward, it will be the first in Arizona in eight years. The last was the execution of Joseph Wood in 2014, which was badly botched. Wood lay on the gurney for nearly two hours, still alive, after having been injected 15 times with lethal drugs.

On Thursday, Dixon's capital defense attorneys laid out their case first. Dixon was not present. He had waived his right to attend the hearing and remained at the state prison in Florence.

"At this point, 44 years after Ms. Bowdoin's tragic murder, Clarence is a frail, blind, elderly, and mentally incompetent man whose health is rapidly failing him," argued Amanda Bass, a lead attorney on Dixon's case, who has represented several high-profile death row cases.

This was the crux of Dixon's argument: His poor condition and long history of mental illness should spare him. That, regardless of his guilt and the fact that he has never shown remorse for Bowdoin's death.

Clemency boards, as Dixon's attorneys emphasized, are unique in that they are not bound to legal arguments. "This isn't a legal appeal,” Garrett Simpson, a defense attorney working on Dixon's case, told the board. “This is an appeal for mercy.”

Dixon was 21 when he killed Bowdoin. At the time, he too was a student at Arizona State University, though he withdrew from the school a short time later. In the months before Bowdoin's death, he had assaulted a 15-year-old girl. In the court proceedings that followed, he was evaluated by two court psychiatrists, who diagnosed him with schizophrenia. In that assault case, he was found not guilty by reason of insanity.

The judge in that case, Sandra Day O’Connor, directed Dixon to be committed to the state hospital. But, it was reported, county prosecutors never did so. He was instead released back to his unsupervised home in Tempe, where, two days later, he would strangle and stab his neighbor, Bowdoin, after sexually assaulting her.

Multiple evaluations since then have affirmed that Dixon suffers from schizophrenia, reporting hearing voices and other hallucinations throughout his life, though jurors were never given information about his mental illness at trial.

Part of that was because Dixon's 2008 trial was unusual. Despite a prior diagnosis of suffering a psychotic disorder, Dixon fired his lawyers during the trial and was permitted to represent himself. One psychologist, John Toma, brought in by the defense to examine Dixon, wrote that this was a concern: "He was clearly not capable of representing himself and his competence to proceed should have been questioned, especially given the fact that he was not treated for his psychiatric disorder," he wrote in a 2012 evaluation.

Dixon's legal team at the clemency hearing brought in Garrett Simpson, Dixon's defense attorney at the time, who testified that he regretted not raising the issue of Dixon's mental state to the court and preventing Dixon from representing himself.

"It was a nightmare,” said Ty Mayberry, another member of Dixon's legal team back in 2008. He attended each day of the trail, he said. “It was almost inhumane that we could not help him in any way... At some points he gave up, I could tell. The prosecutor was objecting to almost every question he asked."

When it came time for the state to present their case against Dixon, they provided a very different picture of this trial.

"This inmate chose to represent himself. He chose to control the trial," said Vince Imbordino, a veteran capital case prosecutor with Maricopa County. The idea that the judge would have let the trial proceed if Dixon was clearly incompetent was "nonsense," Imbordino said. The court had not evaluated Dixon's competency, he argued, because there was no glaring need to.

The state argued that Dixon's attorneys had overblown the impacts of his mental illness and incompetency at trial. Attorneys pointed to the fact that Dixon had filed reasonable motions in his case and still appears to understand much of the proceedings against him, despite some irrational views he holds about his own guilt. Méndez, the board's chair, said that in her reading of the trial transcripts, Dixon had represented himself "very well" during the proceedings against him.

"To suggest that he is in a psychosis or he's delusional is fantasy at best," said John Schneider, representing the prosecution. "By his own admission, he's a serial rapist."

James, Bowdoin's sister, gave an emotional address to the board, requesting that they deny Dixon's petition for clemency. "I'm speaking to you today from the heart," she said, saying she wished that the "prompt and final conclusion to this case be upheld" after all these years.

Shortly after James took the stand, the board deliberated for about 20 minutes. All four current members, Salvatore Freni, Louis Quiñonez, Michael Johnson, and Méndez, voted to reject the clemency petition.

Over the last few weeks, Dixon's attorneys have argued in a special action suit earlier this month that the current composition of this board is unlawful. Three of the four board members are former cops, each having worked over 20 years in the field. Arizona statute requires that no more than two members of the board hail from the same professional discipline.

A judge dismissed the suit, however, partly on the basis that law enforcement does not constitute a profession.

The legal challenges are likely to continue, however. Dixon's attorneys are making the case that, due to his mental illness, execution would be unconstitutional. That case is still pending in Arizona courts.

Now that clemency is denied, Dixon's fate is in the hands of the courts.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]