The 21-year-old combed through paperwork with them, making sure all the T's were crossed and the I's were dotted. They were filling out forms to reapply for The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, better known as DACA, which protected from deportation almost 800,000 young adult unauthorized immigrants like her while permitting them to work legally in the U.S.

Most of these Dreamers were filling out their forms in a rush. When President Donald Trump announced on September 5 that DACA would end and left it to Congress to find a solution in six months, he gave immigrants whose DACA permits expired by March 5 one month to reapply for two more years of protection under DACA.

Thursday was the deadline.

But as Benitez worked with dozens of Dreamers at LUCHA's clinic, she knew she herself couldn't be helped.

Her current DACA permit expires on March 30 — just 25 days after Trump's deadline.

Until Congress makes a move, her future is in limbo.

That's why she wanted to make the most of this final week, assisting Dreamers who could be helped.

Benitez was on a 15-minute break last month when she heard the news that DACA would officially be rescinded.

Veronica Benitez couldn't reapply for DACA after Trump rescinded it, but that didn't stop her from helping others renew their permits.

Courtesy of Veronica Benitez

She has lived in this country since she was 3, brought here from Mexico by her parents. The sole reason she'd been able to land a job at a call center was

“DACA changed my life a lot,” Benitez says. “Before I was scared to go out and I was sad that I couldn’t get a job. … [With DACA] I was able to work, to volunteer, and could help my family financially.”

But with Trump’s announcement, she was overcome with anxiety.

Benitez is fairly certain that her permit expired on March 30 — only 25 days past the deadline. But then she thought: What if I'm wrong? What if it expires March 3?

She had a sliver of hope. She considered this as the hours dragged by at work.

When she finally returned home, she ran into her mother’s bedroom. Her DACA paperwork was under the bed in a box.

Papers rustled and the words stung when she read them: March 30.

She’d missed the deadline by less than a month. If Congress doesn’t pass legislation to protect Dreamers by this spring, Benitez could lose her job or even face deportation from the land in which she has lived the past 18 years.

Although Benitez couldn’t renew DACA, that didn’t stop her from trying to help others who could.

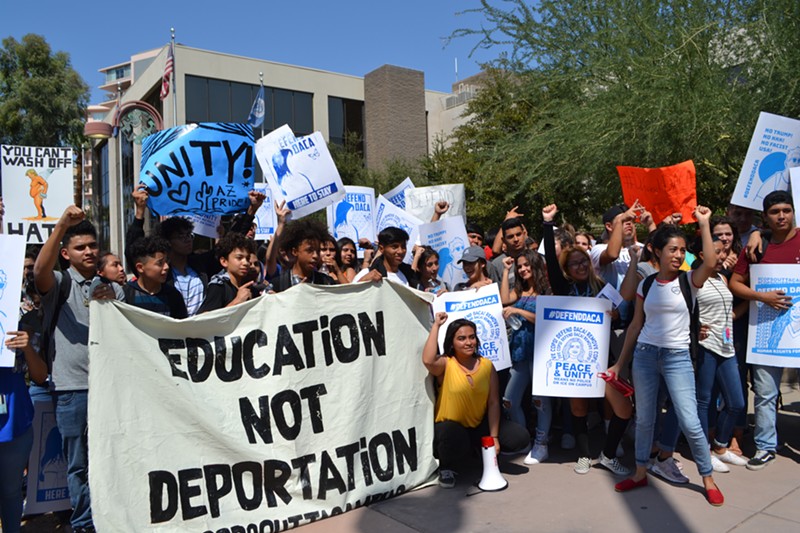

The Monday after Trump’s DACA announcement, LUCHA and the Arizona Center for Empowerment, or ACE, set up the clinic for DACA recipients who were eligible to renew.

Aldo Gonzales, the immigration services coordinator for ACE, said volunteers like Benitez and pro bono lawyers helped DACA recipients fill out their paperwork for most of September.

When the clinic opened the Monday after the DACA announcement, a rush of about 20 immigrants came in for help. Though the number of applicants coming to the clinic slowed as the month inched on, they wanted to keep it open until the final second.

As Dreamers came carrying folders and bags full of papers and permits, Benitez helped them fill out applications.

"It gave me comfort," she says. "Knowing that I couldn’t [renew], but I could help others to do it."

Volunteers ensured immigrants didn’t fill out sections of the DACA application that were only for first-timers. They scrutinized each form, so that no one missed a question, and would recommend a lawyer if the applicant had received a parking ticket or misdemeanor since their last DACA application.

Gonzales says if an application is filled out incorrectly and sent to the government, the paperwork could be returned — but likely not in time for the October 5 deadline. That's why everyone in the clinic had to be on their best game.

DACA renewal packets had to be turned into the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS.

Between September 5, when the president announced the end of DACA, and October 4, 54,000 people submitted renewal requests, according to Maria Elena Upson, a public affairs officer for USCIS. More than 150,000 DACA recipients were eligible to apply for the renewal and 58,000 had applied before September 5.

But, like Benitez, some applicants who sought out the clinic were beyond help. Some would come in not knowing about the March 5 deadline.

Benitez knew how they felt. As she sat in LUCHA’s office day after day, she felt let down all over again when someone came in who was in her situation.

“There was a bad feeling when unfortunately they couldn’t renew,” Benitez says. “I understood those sad feelings … but it then was a great feeling to tell them and get them excited to fight back and pressure politics to do something better.”

She has tried to remain optimistic. She wants to stand with LUCHA and fight for a clean Dream Act. The original DREAM Act — Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors — was introduced in 2001. The legislation aimed to give undocumented children a path to citizenship, but it stalled in Congress. A current version of the Dream Act was introduced in July by Senators Dick Durbin of Illinois and Lindsey Graham of South Carolina.

During that 15-minute work break when she learned DACA was suspended, Benitez said the thing that got her through was a text from her father.

“It’s going to be okay,” he wrote. “Better things are coming your way.”

Benitez took this to heart. The way she sees it, good things come to those who do good.

“I have faith that something will happen,” Benitez says. "