But ASU's media relations department routinely embarrasses the Cronkite reputation, ignoring public records laws that the school teaches its students.

Case in point: The university last month finally got around to releasing public records that I'd requested in friggin' September 2016. (Full disclosure: I'm a Cronkite grad, class of '97.)

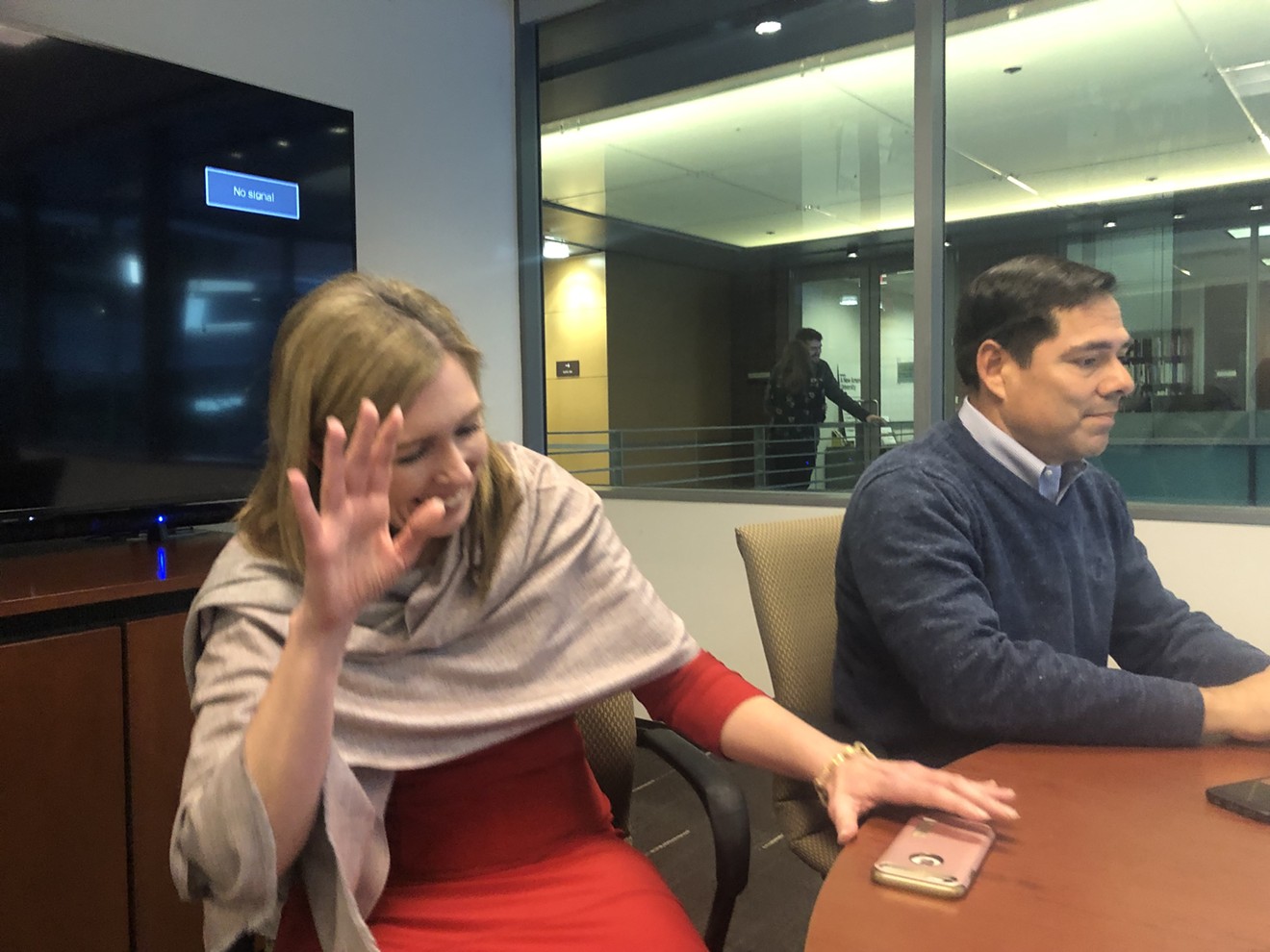

When I pressed ASU for a reason for the epic delay, Katie Paquet, vice president of ASU's Media Relations and Strategic Communications office, agreed to meet me at the Fulton Center last week to talk about it. She described an unwritten policy ASU had in which police reports weren't released to the media until the Maricopa County Attorney's Office notifies ASU the case has been fully adjudicated.

She claimed this was not unusual, despite admitting she was an avid newspaper reader and therefore would know it was. Police reports are routinely released to the media by police agencies long before a court case is finished.

On top of everything, Paquet, the face of media relations at ASU, while conducting public business in a public building, said she didn't want her photo taken. Phoenix New Times took one anyway.

Subsequent statements to New Times by Phoenix police, the state's ombudsman's office, and even the Maricopa County Attorney's Office disputed the validity of Paquet's explanation, and by extension, ASU's alleged police-report policy.

The records involved the criminal case of ex-ASU student Xiaoyuan Zhang — you may recall him, the Chinese foreign exchange student who confessed he had a "dirty mind" after he was caught that month taking photos and videos of women in an ASU restroom, a local grocery store, and a mall.

Zhang was sentenced to 10 years of probation in January 2017, and deported to China in April 2017.

The case received worldwide attention at the time, with details of the sordid incident released by state and federal courts. Following Zhang's arrest, I submitted a request for a police report from ASU police, the agency that had investigated the crime, and a request for evidentiary photos that Zhang took "that DO NOT show nudity or any victim's identity."

Two weeks ago, ASU police notified me that the records were ready. But only the police report was ready. The school was still deciding whether to release the redacted photos, said Brenda Carrasco, ASU's police information officer. The police report, by the way, added no new information to what reporters had learned back in 2016.

Carrasco said the Maricopa County Attorney's Office may have only just authorized the release of the records.

That turned out to be incorrect info. But at first, I thought it might be related to County Attorney Bill Montgomery's letter to law enforcement agencies that caused such a row last year. As the Arizona Republic described it at the time, Montgomery was trying to "usurp police control of records [and] video" by intimidating police agencies with possible financial consequences.

However, Montgomery's letter referred primarily to images and personal identifying information of crime witnesses or victims. Since I'd requested that such things be redacted from any records released to me, this wasn't an issue.

And besides, in spite of the letter, metro Phoenix police agencies did not begin seeking prosecutorial review, input, or approval, of the records they released to the news media.

Except for ASU PD, it seems.

A couple of days after ASU PD released the Zhang police report, Carrasco said the photographs were ready to be picked up. As expected and hoped for, the photos were redacted so well — pixelated, in this case — that no person, and nothing inappropriate for publication in a family newspaper, were visible.

Paquet, who's been in her position for about two years, later explained that the unwritten policy requiring Montgomery's office to approve or otherwise notify ASU it was safe to release the records had been implemented to avoid compromising an active investigation or a criminal case.

In other words, ASU was intentionally ignoring the groundbreaking, 1993 Arizona Supreme Court ruling in the case of Cox Arizona Publications versus former Maricopa County Attorney Tom Collins. The opinion said that cop shops and prosecutors can't use the old "active ongoing criminal prosecution" excuse as a general rule to thwart the release of police reports, and that if records are withheld, the agency must show how the release of the records would cause harm."Generally, we don't wait too much on what the county attorney says if we're going to put out any reports." — Phoenix police Sergeant Tommy Thompson

tweet this

But in policy and practice, as Paquet indicated, ASU goes even further than blowing off case law. ASU requires that it first receive a notice from Montgomery's office that the case has been adjudicated. Never mind that the case was actually adjudicated in January 2017, and Montgomery's office sent that notice to ASU in August 2018.

"Our lawyers are saying [the policy's] consistent with case law," media relations officer Jerry Gonzalez said in the Fulton Center meeting with Paquet.

ASU sent an official response after the meeting:

"ASU’s policy, which is consistent with Arizona public records law, is to not release any evidence that could potentially compromise an active investigation or prosecution of a criminal case. ASU received a final disposition letter from the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office dated August 2, 2018 pertaining to the Xiaoyuan Zhang case stating: ‘the above case has been finalized in court.’ At that time, ASU processed the original records request from The Phoenix New Times relating to this case and the request has been fulfilled.”

Even assuming ASU's explanations are truthful, it still took an incredible seven months to pixelate a few photos and draw black lines through victims' names in the 2016 report.

The prosecutor's office and the county's largest police agency, Phoenix PD, didn't back up ASU's explanations.

Amanda Steele, spokesperson for the county attorney's office, said the office sends police agencies a "final disposition letter" that in many cases "allows law enforcement to move forward with the release of property." "The final disposition letter is not connected to any involvement from MCAO with the release of public records," she added.

Phoenix police, which handled 88,000 requests for public records last year, said the release of public records under state law is "up to us."

"Generally, we don't wait too much on what the county attorney says if we're going to put out any reports," Phoenix PD spokesperson Sergeant Tommy Thompson said.

Danee Garone, staff attorney for the state ombudsman's office, said it would be a "rare situation" in which a law enforcement agency could justify withholding records through adjudication. But it wouldn't be reasonable to make that a general rule, he added.

In this redacted photo from 2016, Zhang captured the image of a fully clothed woman washing her hands at a sink as he lurked inside one of the restroom stalls. ASU prevented the public from seeing this evidence of Zhang's crimes until last month, two years after the case had been adjudicated.

ASU PD

He said he often fields inquiries from government agencies asking about their responsibilities when they receive a public records request, and he tells them, essentially, "you're the one that received the request. You don't really get to pass that off."

ASU's PR machine needs a journalism law refresher course that the school's J-school could provide.

Reporters who have to deal with the school not as an institute of higher learning, but as a government entity, find out quickly that ASU President Michael Crow runs a tight ship when it comes to media relations.

When the questions are easy, ASU serves the public well, providing information and records promptly. When the questions are tough, or the topics sensitive, ASU's office of Media Relations and Strategic Communications shows its obstinate side.

Christopher Callahan, dean of the Cronkite school, didn't return a message seeking comment about these issues.

I ran into a Cronkite student last week who has worked at ASU's student-run newspaper, the State Press, and asked her if students complain about transparency issues with ASU's media office. She said yes.

ASU still has several unfulfilled, outstanding records requests from New Times reporters that were made in September and November. But they're not police reports.

What unwritten policy is stymieing those requests?

If only as a university it lived up to the pro-First Amendment spirit of the Cronkite school, such questions wouldn't come up.