In 1998, Granados was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison, with no possibility of early release before 25 years. But now, a quarter-century later, just what kind of early release Granados could receive is the subject of a lawsuit from the victim’s brother, Dan Levey.

Granados was scheduled for a parole hearing before the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency on July 24. But less than 24 hours before it was set to begin, Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Frank Moskowitz granted Levey a temporary restraining order delaying any parole hearing while the lawsuit continues.

In his lawsuit filed June 21, Levey contended that Granados is only eligible for “executive commutation,” which only the governor can grant. Additionally, Levey claimed that the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry violated the Arizona Victims’ Bill of Rights, improperly making its determination about Granados’ parole eligibility while “failing to hear victim’s objections.”

Gretchen McClellan-Singh, the executive director of the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency and a defendant in the case, declined to comment to Phoenix New Times. So did the Arizona Attorney General’s Office, which is representing McClellan-Singh and ADCRR Director Ryan Thornell in the case.

Attorneys for Granados did not respond to a request for comment, though they argued in court filings that Granados’ plea agreement explicitly states he is eligible for parole.

Levey is hardly new to such a fight. Since his brother’s murder, he’s spent his life advocating for the rights of crime victims in Arizona. He’s helped change laws to ensure victims get free copies of police reports and that judges read out victims' rights in court each day. He also has served as a victims advocate for former Arizona Attorney General Janet Napolitano.

Now he’s fighting for victims to be heard when parole eligibility is determined by the ADCRR and Board of Executive Clemency. In this fight, the stakes are especially personal for Levey.

His brother’s killer, a man described as “remorseless” by the sentencing judge, has spent 25 years behind bars. And now — contrary to what Levey claims was intended at the time — the state will consider letting him out.

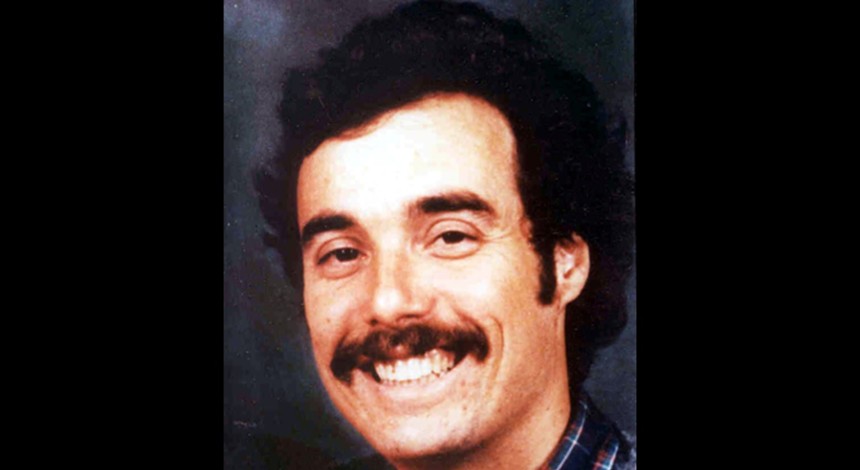

Howard Levey was murdered in 1996. Now his brother is trying to stop the killer from receiving a parole hearing.

Courtesy of Dan Levey

Parole vs. commutation

According to Levey’s complaint, it was always his understanding that Granados would never have a chance at parole.Prosecutors and the Levey family initially wanted to seek the death penalty for the defendant, Levey said in an interview with New Times. But securing such a sentence would require a lengthy court trial, which the family wanted to avoid.

“For almost two years, it lingered as a capital murder case, and they eventually came and said he’s willing to plea first-degree murder,” Levey said. “I still personally wanted to go to trial, but my parents and sister-in-law understandably wanted it just to be over.”

The family accepted a plea agreement with one stipulation, Levey’s complaint said: that Granados would spend the rest of his life in prison with no possibility of parole. Commutation, which is much harder to secure, would still be a possibility after 25 years. The Board of Executive Clemency can make sentence commutation recommendations, but only the governor can commute a sentence.

“We knew that there would likely be some type of hearing, but we thought it was commutation,” Levey said.

The ADCRR determined otherwise – without allowing Levey’s objections to be heard, his suit claimed. In May of this year, the ADCRR determined Granados was eligible for parole. When Levey disputed that conclusion, the department responded that “a simple internal review of documentation” showed Granados was eligible for parole.

The ADCRR declined to let Levey plead his case to the contrary, acting “in excess of its authority” and depriving him of “fundamental constitutionally protected rights.”

The plea agreement Granados signed back in 1998 indeed stated that Granados could receive parole after 25 years. However, Levey’s complaint claimed that prosecutors and the court were using the terms “parole” and “commutation” interchangeably and that Granados was never intended to receive parole. According to the suit, “All family members and all participants at sentencing knew that the sentence imposed” on Granados “did not allow for parole after a specific term.”

The suit also said that Judge Michael McVey, who presided over the sentencing, made it clear that Granados should never be let out of prison. According to court transcripts, McVey told Granados that he had “absolutely no shame, absolutely no remorse for what you did. None.” Additionally, McVey told Granados that “society needs to be protected from you as long a time as possible.”

McVey suggested that Granados “be required to serve the rest of his life in prison.” But the judge made that suggestion to “any future Board of Parole,” suggesting the possibility of parole existed.

Dan Levey claims the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry exceeded its authority by determining that his brother's killer was parole-eligible.

Katya Schwenk

'No other way to read that language'

In their response to Levey’s request for a restraining order, attorneys for Granados wrote that his plea agreement is crystal clear.The agreement stated that Granados was “not eligible for any release or parole until 25 years are served.” The attorneys also pointed out that “neither natural life nor executive commutation appears in the plea agreement, despite both being lawful sentences in 1998.”

“There is no way to read that language,” wrote attorneys Timothy Eckstein, Travis Hunt and Emma Cone-Roddy, “except to find that Granados was parole eligible after 25 years.”

That disagreement is still to be adjudicated, but Levey has won at least a temporary victory. Moskowitz found enough cause to grant the temporary restraining order on July 23. The case will continue in mid-August, when Moskowitz will determine if Granados will receive a parole or commutation hearing.

Levey will have a right to be heard at either. He’ll be able to tell the Board of Executive Clemency how his brother was an “unpretentious gentle soul” and a “family guy” who came from a close-knit home. He’ll be able to share how Granados’ “complete random act of violence” stole a father from his two children. The board will listen before making a decision.

Levey thinks that should have happened in the first place, before the ADCRR designated Granados as eligible for parole.

“These designations have a substantial impact on possible release from confinement,” his complaint stated. To shut out victims from those determinations, it continued, disregards victim’s “rights to be heard and to due process and to treatment with fairness, dignity and respect.”