“It’s pretty rare for congressional candidates to put up their own signs,” he wrote.

Quickly, the post generated criticism. Hamadeh had erected his sign earlier than Arizona law allowed. “It’s pretty rare because most candidates don’t usually tweet out when they’re breaking the law,” chided Democratic state Sen. Anna Hernandez.

Hamadeh shot back with a screenshot of Peoria’s political sign code, which allows political signs to go up as early as May 1, a day before his post. There was only one problem: Hamadeh’s photo was taken at the intersection of Bell Road and Coyote Lakes Parkway.

That’s not in Peoria but in Surprise, which didn’t allow political signs to go up for another three weeks. Hamadeh soon deleted the second tweet.

The Hamadeh sign kerfuffle was the latest in a longstanding Arizona election tradition: freaking out about campaign signs. Every election cycle, Valley drivers and pedestrians are increasingly subjected to barrage of large polypropylene signs posted along their daily commute routes. The signs crowd street corners with the smiling faces and bolded names of innumerable candidates for political office.

And just as the signs dominate the landscape every election cycle, so do beefs about them on social media. Every election season brings roughly a dozen sign-related tiffs that start online and spill into newspaper and TV reports. When they’re not arguing with each other about the issues, candidates argue about each other’s signage.

In past years, candidates have placed cameras near their signs to catch thieves. Back when signs were made of wood, a veteran political operative remembers, one man stole so many of them that he was able to reroof his home. During the 2020 presidential election, sign-stealing became so rampant, campaigns set up websites for people to request replacements. This year also has featured more than its share of sign drama.

Weeks after Hamadeh caught himself breaking the law, Democrat Conor O’Callaghan posted a photo purporting to show Republican Rep. David Schweikert taking down O'Callaghan's signs. “A new low,” O’Callaghan wrote, “even for him.” Around the same time, Surprise City Councilmember Aly Cline was accused of ripping down the signs of her opponent in the city’s mayoral election, claiming they were placed illegally on city property.

In July, signs for Democratic U.S. House candidate Amish Shah began appearing on the lawns of people who didn’t request them, leading Shah to apologize. A month later, Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego and little-known Republican challenger Matt Evans sparred with each other through news reports, each accusing the other of violating Arizona’s sign laws.

Yet for all that angst over campaign sign violations — for all the Twitter cops blaring their sirens when someone steals a sign or places it improperly — almost nobody is ever actually punished for breaking the law. The cities whose job it is to enforce the law hardly ever bother pressing charges. In Phoenix, the largest city in the Valley, there have been only two campaign sign-related prosecutions in the last 10 years.

“The thing that frustrates me the most is watching volunteers and candidates get in arguments on social media, or even at times, go to the media about their signs being watched or taken down,” said Democratic strategist Tony Cani of Slightshot Campaigns, “because it’s just a huge waste.”

That’s Arizona politics for you: all sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Arizona has more permissive campaign sign laws than many other states.

Courtney Pedroza/Getty Images

Signs everywhere

If Arizona has a lot of sign wars, that’s because Arizona has a lot of signs.The First Amendment generally limits how cities and states can regulate political signs, according to Freedom Forum, but municipalities can restrict where and how they’re displayed. In many states, campaign signs are not permitted in a public “right of way.” Signs are mostly displayed in the yards of private homes, not along major intersections.

But that’s not the case in Arizona, where political signs litter street corners during election season.

“The street corner signs, those signs really don’t appear in most places around the country,” said Cani, who has worked on campaigns in multiple states. “It’s a very unique Arizona thing, and it’s been like that for a long, long, long time.”

They’re everywhere in the Valley, and whether they actually work is an open question.

Cani thinks placing colorful political signs on every corner is as effective as yelling a candidate’s name at passing cars. “Plus voters and drivers hate them,” he said. Republican strategist Paul Bentz of HighGround agrees that they’re “a total pain” but thinks that the pain does come with some gain. Signs do “build the overall awareness of a campaign,” he said.

The science is mixed. In 2015, a Columbia University study determined the impact of campaign signs was "probably greater than zero but unlikely to be large enough to alter the outcome of a contest that would otherwise be decided by more than a few percentage points." Cani noted that Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs didn’t plaster intersections with signs in either of her campaigns for secretary of state or governor — “Proof,” he said, “that you can win without the signs.”

However, a 2011 study conducted by Vanderbilt University came to a different conclusion. The study posted signs near a school for a fake city council candidate named Ben Griffin and then surveyed residents about their preferences. Nearly a quarter of respondents listed the fake candidate in their top three picks. That name recognition means something, Bentz said.

“Signs alone do not win elections,” the Republican strategist said. But “it is a mistake for campaigns to not do signs at all.”

Notably, Arizona also has a rich history of signs for fake candidates. Valley residents have gotten to know “candidates” Gina Schuh, a wheelchair user whose signs promised “I’m not running for anything," and Tyler Watson, whose signs said “is crossing his arms.” That’s to say nothing of Arizona mainstay Dixon Butts of “America needs Dixon Butts” fame.

Whether campaign signs work or not, they’re indisputably everywhere during each election cycle. And each election cycle, they inspire some of the pettiest political turf wars imaginable.

Republican state Rep. Kelly Townsend once installed a game camera to catch people who vandalized her campaign signs.

Jacob Tyler Dunn

The letter of the law

Arizona’s campaign sign laws are fairly simple.A.R.S. 16-1019 says campaigns can post signs in public rights-of-way no earlier than 71 days before a primary election and no later than 15 days after the general election. Candidates who lose their primary must remove their signs within 15 days after the primary. This year, that meant signs can be up from May 20 to November 20, though some cities such as Peoria allow signs to be posted earlier than that.

Additionally, the law states that stealing or defacing a campaign sign is a class 2 misdemeanor, which carries a maximum penalty of four months in prison.

Campaigns and political junkies are ever-vigilant when it comes to catching rule breakers. In 2016, a Paradise Valley man paid $4,000 to install security cameras in his bushes to catch people stealing his Donald Trump signs. Two years later, state Rep. Kelly Townsend installed a game camera — normally used to catch candid images of wildlife — after her signs in Mesa were repeatedly vandalized. Around that same time, signs for Arizona Corporation Commission candidate Rodney Glassman were defaced by someone who cut off the first two letters of his surname, thereby instructing voters to support “Rodney assman” instead.

In 2020, so many “Arizona Republicans for Biden” yard signs were stolen that property owners installed cameras or covered their signs with Vaseline or glitter to deter thieves. Working for Joe Biden’s campaign at the time, Cani purchased two website domains — theystolemysign.com and azyardsign.com — to allow supporters to request replacements.

The same paranoia exists in nonpartisan races, about which the state’s sign law is less than specific. Many nonpartisan candidates do not face a primary election but can still post their signs during primary season, leading to erroneous too-early accusations this year against Kate Gallego and a slate of Scottsdale school board candidates. The latter instance prompted Scottsdale to look more closely at the law.

“State law on this subject does not currently provide separate periods for primary and general elections, only that single span,” a Scottsdale spokesperson told Arizona’s Family in a statement. “State law supersedes Scottsdale’s local sign regulations, and the city must follow the State law.”

But what happens when someone does violate Arizona’s campaign sign laws? Finger-pointing, handwringing and … not much else.

It's a class 2 misdemeanor to deface or vandalize a campaign sign, but almost no one is ever prosecuted for it.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

No enforcement

The job of policing sign violations falls not to the state but instead to local jurisdictions. Cities and towns mostly are limited in what they can do — and they often choose to do even less than that.The law says that if a municipality “deems that the placement of a political sign constitutes an emergency, the jurisdiction may immediately relocate the sign.” The law does not define “emergency,” though it does allow municipalities to remove signs “placed in a location that is hazardous to public safety.” When signs are removed under emergency conditions, cities must notify the candidate or campaign that placed it within 24 hours. If there’s no emergency, there are some hoops to jump through.

When signs are placed when and where they shouldn’t be — or when they’re too big or don’t include mandated contact information — cities must give campaigns 24 hours to fix the issue before confiscating a sign. Even then, campaigns have 10 business days to “retrieve the sign without penalty,” though the law does not state what the penalty would be.

In Phoenix, the largest city in the state, it seems nobody has ever found out what that penalty is. Arizona’s campaign sign law is enforced by the city’s Planning and Development Department. Despite the constant social media grousing about sign violations, Phoenix public information officer Teleia Galaviz said the department has not yet imposed penalties on any campaign. She noted that the department has received 24 sign-related complaints this election cycle. Because the city "prioritizes education" over penalties when enforcing sing laws, all 24 complaints were "resolved without need for further enforcement," Galaviz said.

Sign stealing — or removing, altering, defacing or covering signs — is only slightly more enforced. According to A.R.S. 16-1021, the Arizona attorney general is in charge of enforcing all election laws regarding races for state office, including campaign sign laws. For local races, jurisdiction falls to city or county attorneys.

But don’t expect to see Attorney General Kris Mayes or Maricopa County Attorney Rachel Mitchell prosecuting sign thefts. The offices of both told New Times they’d send those cases elsewhere, likely to city courts or county justice courts. And while sign thefts happen all the time — “People get too obsessed with this, and now you’ve got people on your campaign going to take other people’s signs down,” Cani said — don’t expect those courts to do much, either.

In Phoenix, charges were filed in just two sign theft cases in the last 10 years, according to city public information officer Dan Wilson. One of those, Wilson said, was a 2018 case that involved “a person experiencing homelessness who claimed to have found the signs in the trash." That charge was later dismissed. The second happened in 2022 after a police officer “saw an individual taking a bunch of signs down,” Wilson said. That resulted in a fine.

Short of catching people red-handed — either in possession of a sign or by identifying them on camera or by their license plate — “there’s very little that can be done to these people,” said Bentz, the Republican strategist.

Sometimes, though, justice actually is served. In July, the husband of Yavapai County superintendent candidate Kara Woods was caught on camera stealing a sign belonging to her opponent, Steve King. Steve Woods was cited with a misdemeanor, though the current disposition of the charge isn’t clear.

The gambit didn’t even work. Kara Woods lost the primary race by almost 3,000 votes.

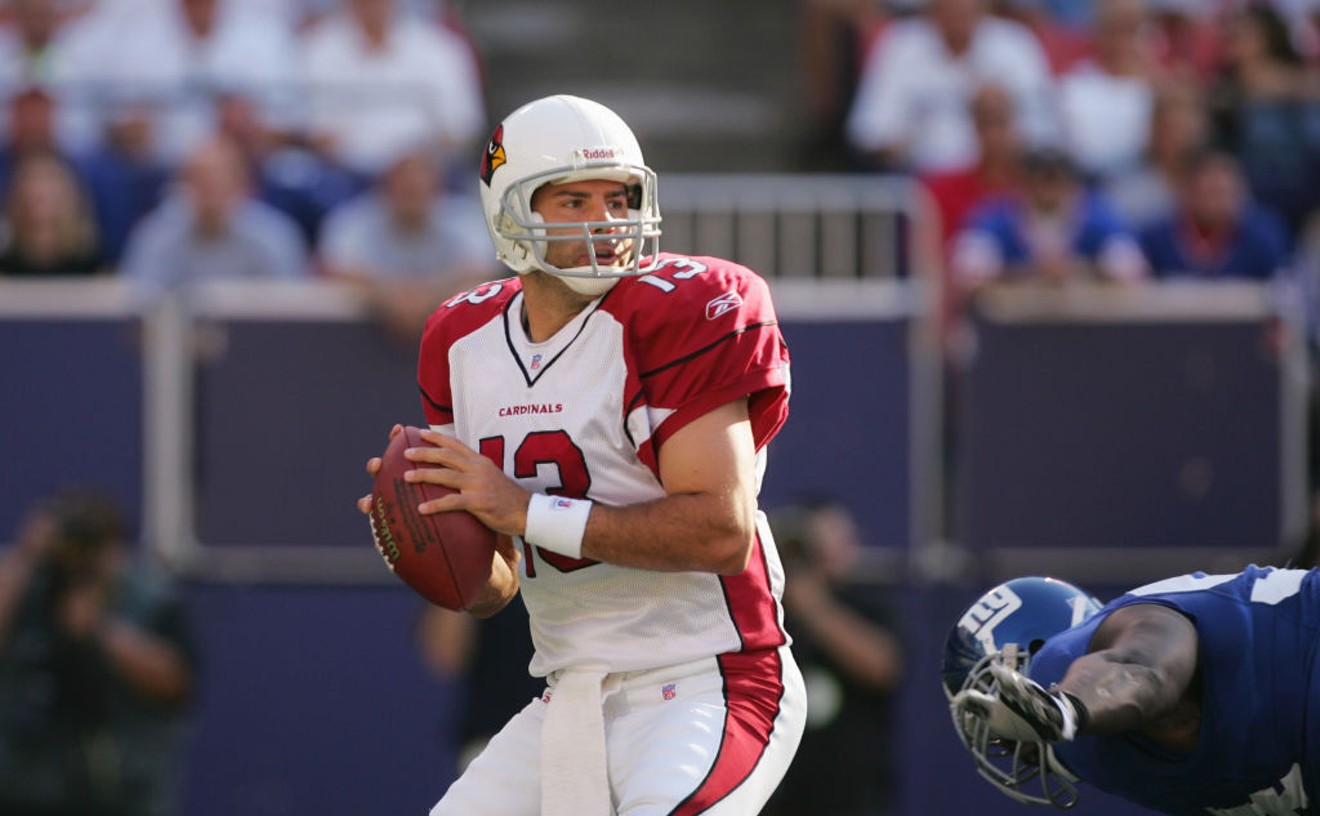

Putting his campaign sign up too early got Republican Abe Hamadeh in trouble on Twitter but didn't affect his successful primary campaign for Congress.

TJ L'Heureux

Three months to go

As far as campaign sign scofflaws go, Hamadeh’s boldness stands out. He posted his sign in Surprise on May 2, a whopping 18 days before he was allowed to do so.It’s not clear if the city removed the sign, but it hardly mattered. Hamadeh won his primary and is expected to sail into the House of Representatives in Arizona’s deep-red 1st Congressional District. That sign may not have contributed a single vote to Hamadeh’s campaign — there is no way to know for sure — but at least it created a social media fuss.

“I don’t think they’re the most important part of a campaign,” Bentz said, “but they’re certainly the most visible part that brings out the most passion among people.”

Residents of Hamadeh’s district now can expect to see those same signs — as well as those of everyone else on the November ballot — for the next three-plus months. After Nov. 20, all campaign signs finally are supposed to come down.

Not that anyone will be paying attention.