Shortly after 6 p.m. on June 25, 2018, two U.S. Navy chief petty officers clad in crisp white dress uniforms were driving from Luke Air Force Base west of Glendale to a house in the far northern reaches of Peoria.

There had been a "flight line mishap" involving a junior sailor and a helicopter at Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia, and the chiefs had the unenviable task of informing that sailor's parents about the accident. The two chiefs — casualty assistance calls officers (CACOs) — had been instructed to tell the parents that their son was gravely injured, but still alive and in the hospital.

By then, though, news of the mishap had already been leaked to the Navy Times: The sailor was dead. When the CACOs saw the article, they pulled their car over to the side of the road and called Norfolk just to confirm.

Again, they were ordered to tell the parents the sailor was alive but seriously injured. After the chiefs mentioned the news article that already had been published, the helicopter squadron finally admitted the truth.

Brandon Caserta, a 21-year-old aviation electrician's mate third class, was dead, and the chiefs now had to inform Caserta's parents that the Secretary of the Navy wanted to express his condolences because their son was gone.

Caserta's parents, Teri and Patrick Caserta of Peoria, already had an inkling that something was seriously wrong. Through no fault of his own, Brandon had suffered some serious career setbacks and was working for what investigators would later call a toxic, abusive supervisor. His mental health had deteriorated to the point that he sent a final text message to his parents: "Just know I love you."

He then removed his helmet and threw himself into the spinning tail rotor of an MH-60S helicopter. He died instantly.

A 2021 research project indicates that 20 years after the 9/11 attacks, more than 30,000 active duty service members and veterans have died by suicide — over four times the number of combat-related deaths in the same period. It's difficult to tally the total number of veterans and active duty troops who have died by suicide since the Civil War because there's a history of spotty record keeping and nonstandard definitions of suicide — but some researchers have tried.

In Arizona, military veterans make up about 10 percent of the adult population, but represent about 20 percent of all suicide victims statewide, according to 2021 data from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

As a national holiday, Memorial Day exists to remember the nearly 650,000 Americans killed by enemy forces since 1776. Caserta's parents want Americans to start paying attention to the untold numbers who, in their eyes, were murdered by their own country.

Broken Expectations and Wasted Potential

Brandon Caserta grew up in a Navy household: His dad, Patrick, served for 22 years, retiring as a senior chief petty officer in 2006.

"I would never let my kid join the military, ever," said Patrick, who spent the last 15 years of his military career working as a recruiter. "He could have gone anywhere he wanted to. But we were determined to make sure our son had a different life than we had, and opportunities that we didn't."

Brandon was athletic. He held a black belt in karate and swam competitively.

"You could yell at him and tell him to do 100 pushups, and he'd laugh at you while doing them," Patrick said.

When he was a sophomore at Liberty High School in Peoria, Brandon decided he wanted to be a Navy SEAL. His parents couldn't talk him out of it.

"I knew we were faced with a dilemma," Patrick said. "Either support him and give him everything we possibly can for him to succeed, or go against it. And he's going to join anyway, probably, so we decided to support it."

Potential SEAL recruits go through rigorous screening, even before they report for the famously difficult Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL (BUD/S) course in San Diego. Aside from a daunting physical fitness screening, potential SEALs undergo a thorough physical exam and a detailed psychological exam called the C-SORT, which the Navy says evaluates a candidate's mental toughness and resilience.

Before leaving for basic training, Brandon passed all of these tests. He reported to BUD/S in January 2016, and officially started the course in April, determined not to be one of the roughly three-quarters of students who drop out of training. About two weeks in to his training, Brandon went to see the medics, complaining of severe leg pain. The medics told him it was shin splints, accused him of faking his injury, and said they wouldn't waste an X-ray on him, his parents said.

Shauna Springer, a psychologist who works with the military and veteran community, says that there's a culture within the military that punishes asking for help. This culture, she says, is one of the root causes of the suicide epidemic. Springer recently published the book Relentless Courage, about military and first responder trauma and moral injury.

"Service members give up some of their individual rights when they're in the military," Springer said. "They subordinate themselves to a system that puts people in a position of making judgments about whether they are fit for duty."

For the next week after his first visit to the medics, Brandon would run about 20 miles each day, despite the pain. On May 6, 2016, he collapsed on the beach while carrying an inflatable boat over his head.

The medics relented and ordered an X-ray, and discovered that his leg was broken in two places. He wasn't allowed to continue SEAL training, and was given 30 minutes to choose his new Navy career. He eventually settled on aviation electrician's mate, with the hope he could eventually work his way onto a helicopter flight crew.

After several months of training on his new specialty, Brandon reported to a helicopter squadron in Norfolk, Virginia in October 2016. Despite the thousands of dollars taxpayers spent on his technical training, despite his high scores on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, despite his physical fitness and motivation, Brandon was assigned to the squadron's geedunk — the snack bar. His career was derailed again.

"Losing your career is a major trauma," Springer said. "It's the same trauma as an athlete, who suddenly has a career-ending injury," she added, noting the change separates people from their self-identity.

Springer says that when someone chooses to join the military, they often have a distinct career goal in mind. They want to be a SEAL. They want to travel the world. They want to get technical training. They want to serve their country in some capacity.

Those career plans sometimes don't work out. In a large bureaucracy like the military, something as simple as error on a form could make the difference between serving as a search-and-rescue swimmer or serving as a snack bar attendant. In Brandon's case, there wasn't clear communication between the squadron career counselor and the aircrew personnel, Patrick said. This cost Brandon his orders.

Brandon's case is not unique. New service members are often assigned menial tasks unrelated to their job. They mow the lawn, clean the company office, peel the potatoes, wash the dishes, and paint the side of the ship — despite months of training in their career specialty.

Often, someone might join in a highly technical field like air traffic control or radar repair, only to be assigned to a non-deploying unit, where their daily duties include cleaning, maintenance, and more cleaning.

The Navy recently has been forced to confront this problem aboard the aircraft carrier USS George Washington, where four sailors have committed suicide in the past year — three in April.

Sailors assigned to the ship have come forward complaining of uninhabitable living conditions aboard the vessel, which is currently undergoing a five-year mid-life overhaul at a shipyard in Newport News, Virginia. Crewmembers told national news outlets that there's no hot water, heating, or air conditioning on the ship, and shipyard workers often make noise at all hours. Many of the systems that make the ship habitable are shut down for maintenance.

The Navy's official response fit a theme: Suck it up, snowflake.

Russell Smith, Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy who's the top enlisted person in the service, spoke to the crew in in April after the suicides. In his speech, he told sailors: "What you're not doing is sleeping in a foxhole like a Marine might be doing. The downside is some of the shit that you have to go through logistically will drive you crazy."

Springer says it's not the difficult conditions that drive people to suicide, but a sense of betrayal they feel when the organization they were excited to be a part of throws them under the proverbial bus.

"All of a sudden, everything that you know, the group of people that you love, like family, you're moved into a different life entirely, very quickly at times," Springer said. "When there's a betrayal or an abandonment, then we're talking about not just trauma, but a moral injury as well. And those are some of the hardest for my patients to heal from."

Toxic Leadership

Caserta's parents said their son didn't let his career setbacks get him down. He was excelling in his role at the squadron's snack bar. People liked him. He figured out what candy sold best, and helped the snack bar rake in a bunch of cash. He was even recognized for his efforts.

"They made even more money than they ever made," Patrick said. "And he was labeled the hardest, best worker in the command."

"It was like the water cooler over there," Teri said. "They would go there just to talk to him. They liked him."

It wasn't long until Brandon fell victim to a common problem in the military: toxic leadership. Toxic leadership represents the number one complaint filed with the Office of the Inspector General, according to a 2018 report.

Bullying, hazing, harassment, and toxic work environments are rampant in the armed services. Reports from 2020 found 52 substantiated cases of hazing and nearly 6,300 reported sexual assaults across the services, although actual numbers are likely much higher since hazing and sexual assault are underreported, the same report said.

According to anonymous command climate surveys obtained through a public records request, anywhere between 85 and 98 percent of respondents reported workplace hostility aboard U.S. Navy ships deployed to Japan, for instance.

Springer says a toxic work environment affects most people who serve in the military, and is more likely to lead to thoughts of suicide than engagement in combat action.

"It's these intimate personal betrayals, these sudden changes in identity, group identity, who we are, whether we belong to a group, these are the things that impact us at the core of who we are," Springer said.

In Brandon's case, his leaders seized on the fact that he dropped out of SEAL training to pick on him. In the Navy, someone who fails out of BUD/S is often mockingly referred to as a "BUD/S Dud." Sometimes, it's good-humored ribbing from a friend. In Brandon's case, it came from his chain of command, all the way down to his frontline supervisor, investigators said.

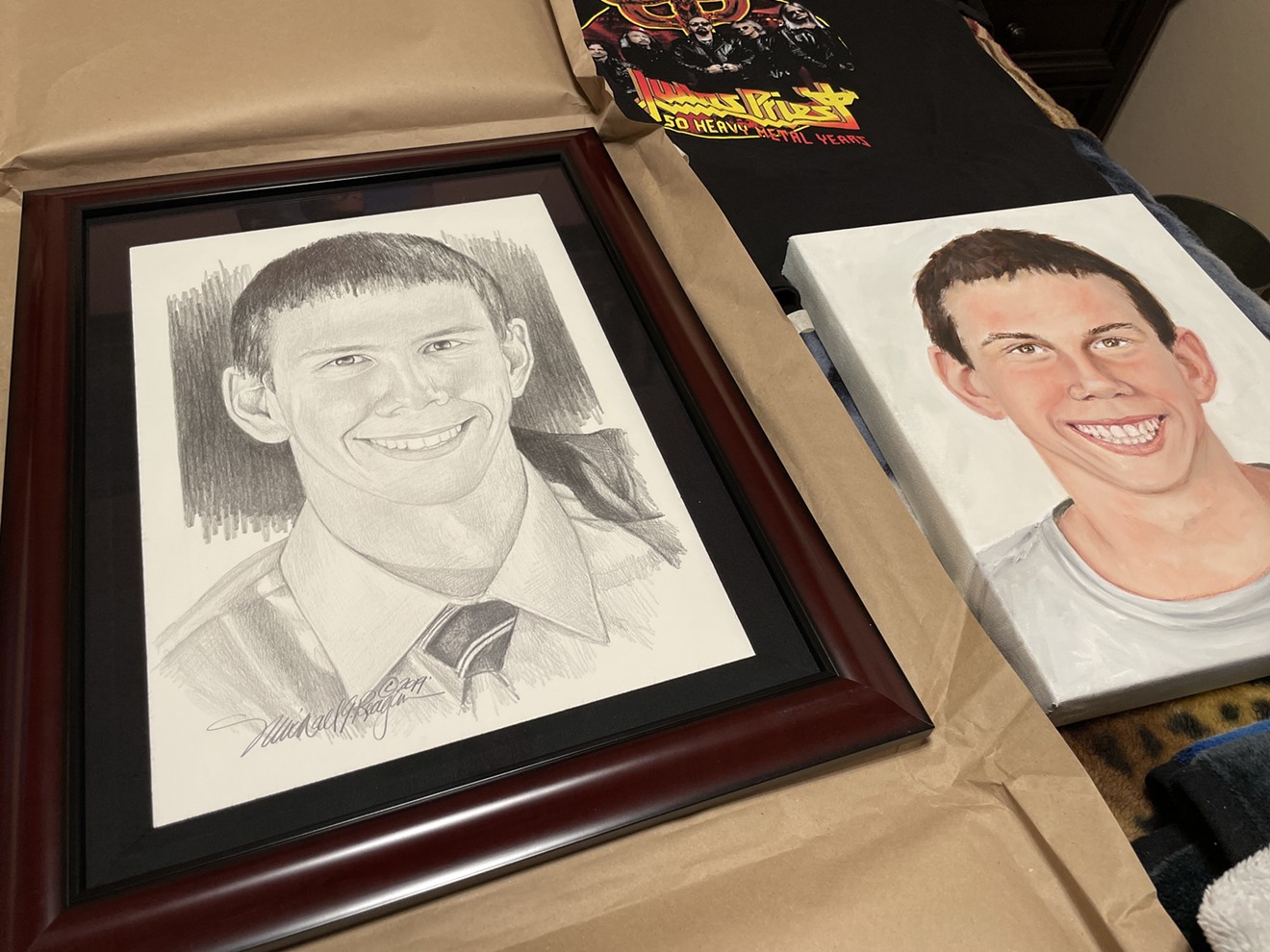

"They started picking on him and calling him a BUD/S Dud," Patrick said. "If you look at Brandon's picture, it'd be hard to criticize him. I guess that was the only thing they could come up with."

His parents said the bullying increased and spread like cancer to the rest of the unit. His frontline supervisor, a first class petty officer, led the charge — even taking bets on whether Brandon would kill himself, Patrick said.

Official investigations conducted by the Navy Judge Advocate General (JAG) and the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) blamed 13 individuals within Brandon's chain of command for creating a hostile environment that led to his suicide.

Caserta's supervisor had been previously counseled for his harsh leadership style, the command's internal investigation said. In January of 2018, the supervisor was removed from his position and ordered to attend anger management classes. After Caserta's death, multiple sailors who worked under that supervisor sent anonymous reports to the squadron commander saying that the supervisor's "harsh and demeaning vernacular" had not stopped.

The supervisor's "noted belligerence, vulgarity, and brash leadership was likely a significant contributing factor to [Caserta's] decision to end his own life," the investigation said. "It is clear from the evidence that [the supervisor's] behavior towards his subordinates was verbally abusive and demeaning."

"In an unhealthy chain of command," Springer said, "a person will be doubly victimized not just by the first thing that happened to them, but by their experience of others pushing that under the rug, and not believing it."

Nobody in Brandon's command was charged with any crime related to his suicide.

"They recommended charges" against Brandon's frontline supervisor, Patrick said. "But they never pursued them." His supervisor was given a derogatory performance evaluation and allowed to continue serving in the Navy, albeit reassigned to a different unit.

"The way they kill these people, it's manipulation, bullying, hazing, they know what they're doing," Patrick said, adding, "Thirteen people [in Brandon's squadron] have blood on their hands."

Is Arizona Doing Enough?

If Brandon had survived his enlistment, he would have returned home to Arizona and applied to join the Phoenix Police Department, his parents said. Fortunately for him, he had a strong support system awaiting his return.

"He was welcome home any time," Teri Caserta said. "There's a video game room with an 80-inch TV. That area was his. Also the bathroom ... the whole side of the house was his. He could have lived here."

Many veterans aren't so lucky. They often join the military to escape difficult situations at home, and, like some people who are released from prison, return to civilian life with zero support, Springer says. They are left to navigate what advocates call a bureaucratic and confusing system of local, state, and federal veterans services.

Veterans in Arizona are almost twice as likely as nonveterans to die by suicide, according to the most recent VA data.

In 2020, the state government budgeted about $80 million to the Arizona Department of Veterans Services. About $1.2 million of that budget — 1.5 percent — went to suicide prevention, according to state budget records. The 2021 state budget cut 12 percent from the department, even though the number of veterans it serves grew by about 4,000.

The state-funded veterans' services are concentrated in the urban areas of Phoenix and Tucson, though most veterans live in rural counties, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

But all the veterans services in the world won't reach everybody, Springer says. The problem is cultural: Veterans have been conditioned to be afraid to seek help. The system is often seen as punitive: A veteran who admits suicidal ideations could be involuntarily committed or have their firearms seized.

"They carry that same mentality of the fear of consequences when they come out of the military into another health care setting," Springer said. "Often, their first instinct is to say 'I don't know if I trust you yet. I don't want to risk losing my firearms, I don't want to risk being put into an inpatient unit.'"

In her eight years working with the VA, Springer says she saw only two veterans hospitalized for suicidal ideation. Neither had their firearms confiscated. But the fear is pervasive, and reinforced through cultural stereotypes.

"I want us to be able to talk about suicidal ideation, the dark things that you go through, without the fear that I'm going to overreact and take away your rights [or] go after your firearm," Springer said.

Caserta's parents don't blame the state or veterans service agencies like the VA. In their eyes, every veteran suicide is the fault of the military.

"Active duty [service] is responsible," Patrick said. "The problem [that led to the suicide] was caused on active duty. It was not caused by the VA."

Just Be a Man, Snowflake

Older generations who are active on social media don't seem to understand why people in the military often choose suicide.

In news articles about Brandon Caserta, some commenters blamed the millennials and Gen Zers for being too sensitive to handle military service. Others blamed the Obama and Biden administrations for catering to so-called "wokeness" at the expense of military lethality. A lot wrote the military isn't right for everybody. That it's not Boy Scout camp; it's meant to be tough. Others say those, like Brandon, who kill themselves, are too weak to be in the U.S. armed forces.

"He's weak? Really? He's weak? He jumped into a tail rotor," Teri Caserta said. "You call that weak?"

Springer agrees. Nobody who makes it through the military's even most basic selection and training process fits her definition of "weak."

"People who enter the military are some of the strongest and bravest people in our society. No question about it," Springer said. "It takes courage to sign a blank check and say, 'I'm gonna go through a rigorous training process and lay aside my individual rights to serve something greater than myself.' That is not a sign of weakness."

Since the 9/11 attacks, more than 30,000 families like the Casertas have been left picking up the pieces after a service member or veteran dies by suicide. In the Casertas' case, they said some degree of purpose was found in Brandon's suicide letter.

"If you read his letter, he sacrificed himself to bring attention to what the command was doing in hopes that he could fix it," Patrick said. "Brandon is the type that leaves a smoking gun."

Patrick and Teri started the Brandon Caserta Foundation, and worked with U.S. Senator Mark Kelly to create the Brandon Act, which President Joe Biden signed into law late last year.

The Brandon Act requires military commanders to allow service members to seek mental health treatment without fear of reprisal. All a service member has to say is, "I have a Brandon Act concern," and their commander is required to refer the member to behavioral health services.

"Thanks to the tireless advocacy of Teri and Patrick Caserta, and bipartisan support in Congress, our efforts will help us confront military suicide head on and save the lives of other young service members," Kelly said in a statement after the bill was passed in the Senate.

Kelly agrees with Caserta's parents in believing Brandon would be alive today if his leadership were forced to refer him for mental health treatment.

Instead, the leaders in Brandon's chain of command were promoted and remain in the service, despite investigations faulting them for his suicide. Navy officials did not respond to a request for comment, but official investigations presented ample evidence of abuse and toxic behavior by Brandon's chain of command.

The investigations found enough evidence to take Caserta's supervisor, a Petty Officer First Class, to Captain's Mast–an administrative disciplinary hearing–for violating the Article 93 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice: Cruelty and Maltreatment. The supervisor could have been demoted, fined up to one month's pay, restricted to the base for 45 days, and been assigned extra punitive duties for 45 days.

Instead, the supervisor was transferred to a new unit with a negative performance evaluation. The investigating officer said punishing the supervisor would take too long and "exacerbate the healing process" for the unit.

After Brandon's suicide, the Navy hastily packed his personal effects and shipped them home. They also sent Patrick and Teri Caserta a so-called gift: the helmet Brandon removed before he killed himself, signed by members of the squadron, like a yearbook.

"They're calling that a gift," Patrick said. "We took that as a friggin' threat, like, 'Go and try and have another investigation.'"

His ashes are scattered atop a butte that overlooks his parents' home in northwest Peoria. His parents say he chose that location so he can continue to watch over them.

Editor's note: Scott Bourque served in the Navy from 2009 to 2014 and completed two overseas tours, including one deployment to Afghanistan.