“Heartbreaking phone calls and emails have been pouring into my office over the past month,” Mayes said. Her voice was steady and stern, and she’d pump her first for emphasis.

Also on the panel were three other attorneys general — Dan Rayfield of Oregon, Keith Ellison of Minnesota and Raúl Torrez of New Mexico — sharing their own encounters with despondent constituents. Each AG spent time peering out across the crowd, taking in the crowd’s stares and disillusioned slumps as if they were addressing their own constituents.

A look around the auditorium, at the people wedged into cheap, bounce-less chairs, was a glimpse at everyday Phoenix, activated. A handsome doctor in a lab coat pored over notes. Young Mexican activists shared their stories of injustice with white women dressed in blazers. Videographers lined the back walls, recording this scorching tinderbox in real time.

Editor's Picks

America is only halfway through Trump’s first 100 days, and already gatherings such as this, in which the top law enforcement officials from four states are meeting up in our pivotal purple state, show the urgency of the public’s fears. True to his word on the campaign trail, Trump has governed as a chaos agent. He has antagonized NATO, abandoned Ukraine, embraced Vladimir Putin, crippled the IRS and Securities and Exchange Commission, started trade wars with our closest trading partners and installed a pugnacious Fox News host to run the Department of Defense.

“Reform should be done lawfully,” says Mayes. “Through the constitutional processes that exist for that very purpose, not through unilateral decisions that upend the livelihoods of hard-working Americans, throw entire communities into chaos or violate the privacy of American citizens.”

Trump also put the world’s purported richest man, Elon Musk, in charge of reshaping the federal government through madcap cuts to the federal workforce. Musk and his quasi-agency DOGE (Department of Government Efficiency) have blitzed workers who serve the public at large — slashing weather forecasters, air traffic controllers and national park rangers. Musk has also fired workers who care for the most vulnerable among us and frozen federal money for programs that will be lost without it.

In the high school auditorium, Arizonans hit by these cuts shared their stories with one another and with the attorneys general. A public health activist recounted having to lay off three employees. An OB-GYN described helping patients stockpile hormones. A conservationist explained the dangers now facing understaffed national parks.

Then Kristin Fray rose to greet the room. She, too, is no elected official. For the past 10 months of her 19-year career, the music therapist had worked at the Carl T. Hayden Veterans Administration Hospital in Phoenix. There her work supported the mental and emotional health of veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, aftereffects of Agent Orange exposure and other maladies. Then, in February, DOGE and Trump slashed some 1,400 VA jobs nationwide, with many more cuts promised. Music therapy was among the casualties.

“This was my dream job, and it took 20 years to achieve,” Fray told the crowd. “I was terminated immediately. That meant that not only could veterans no longer access the services I provided, but I could not follow my own code of ethics, providing termination services to the veterans. These veterans, some of whom are very fragile, were unable to have that closure, which puts them at risk for depression, anxiety or even suicidal ideation.”

It’s not clear whether the notions of shame or service resonate in the executive branch right now. But on the chance we can come back from this moment when PTSD treatments for Iraq War veterans are regarded as government waste, we should talk about music therapy and what it means to people. Arizona’s music therapists have always done more than the public realizes to help patients who could otherwise be unreachable. Neither these exceptional therapists — nor the patients who reinvent their lives with the use of music therapy — deserve to be left behind.

‘Kind of a voodoo scientist’

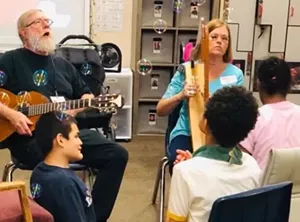

The most generous view of the Trump administration’s cuts to music therapy is simply that they know not what they do. Even people who become music therapists — several of whom participated in this story — didn’t understand music therapy's scope before they began their work in the field.“People think we’re kind of a voodoo scientist,” says Maria Chase Young, a music therapist at ACCEL, an educational nonprofit that serves kids and adults at nine campuses around Arizona. “But we’re trying to change that.”

Music is, at its core, a form of nonverbal communication, and as such, it can cross boundaries where words alone may fail. The godfather of music therapy in the United States was a University of Kansas psychologist named E. Thayer Gaston, who after World War II worked with veterans experiencing shellshock (what we’d now call PTSD). He was a pioneer in a field aimed at healing the brain and the self. At the time, Chase Young says, music therapy was seen as a way to “lift spirits, and make people happy and healthy in mind, body and soul” — that is, not that much more than music.

Yet as Thayer and other practitioners developed the field in the 1960s and beyond, they began to unlock more benefits. Charlotte Stewart, a music therapist and the founder of Mella Music Therapy — a practice in Mesa that treats adults with a range of neurological conditions — says the field evolved from its origins in recreation to a more robust clinical view of patients. When she designs a treatment plan, Stewart first considers her patient’s ability to function physically, emotionally and cognitively. She then designs music interventions to address goals in those areas.

“Music,” Stewart says, “is the prescription.”

That breadth of considerations regularly produces a more varied treatment approach — often a cocktail of speech and physical therapy with a dash of psychotherapy. Individual patients are just as varied. Music therapists treat children with autism or developmental delays, people with schizophrenia, people recovering from strokes, people who have survived abuse or injury, and people seeking palliative care. A therapy plan may involve various disciplines and approaches, but often it boils down to using music to reach afflicted patients to accomplish non-music-related goals.

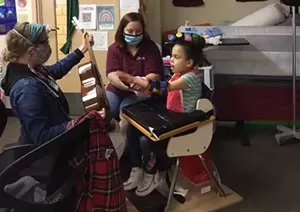

Stewart, for instance, previously helped a stroke victim by using his favorite songs to manage a depressive state after the patient suffered a significant loss in communication skills. Kelly Kwok, a music therapist at ACCEL in Glendale, meanwhile, says she uses lesson-oriented music therapy to address a student’s needs.

Suzanne Oliver, a music therapist at Neurologic Music Therapy Services of Arizona, in Phoenix, works primarily with autistic people and uses music to help them overcome "frontal sway loops, where they do repetitive things over and over again,” she says. If there's a need, music therapy has an approach to empower patients.

"An average session is establishing rapport with the person and assessing where they're at," Oliver says. "How do I shape music exercises and music experiences that'll create a brain change in that session — but then also long-term."

She and other therapists say they grapple with the rapid "mainstreaming" of music therapy. A couple decades ago, Oliver says she had to leave Arizona to pursue music therapy because there were simply no available jobs. Today, Arizona State and University of Arizona both offer undergraduate degrees in music therapy, among 70 college programs nationwide approved by the American Music Therapy Association. As of 2024, the Certification Board for Music Therapists counts 10,511 board-certified music therapists across the United States — double the total of just 13 years ago.

These professionals are finding ample evidence that music therapy works. A 2022 meta-analysis of 47 music therapy studies (published in "Health Psychology Review") found that they showed consistent "medium-to-large beneficial effect on stress." Similarly a 2017 systematic review (from "Pain Physician Journal") of 1,178 participants showed that music therapy "reduced self-reported chronic pain and associated depressive symptoms."

The proof is there. You just have to listen for it.

‘Everything is about music now’

Lenny Henderson is one person for whom music therapy's benefits are beyond theoretical.For the former helicopter medic, music has always been a companion — you’d often find him playing a harmonica he’s had for decades. But when he suffered a debilitating stroke several years ago, he struggled with loss of speech, of memory and of emotional control. Music therapy helped him to recover his very life.

"I was blessed by God once more to be able to read, write, ride a bicycle and do many things as before," he wrote via email. His hobbies now include crafting cigar box instruments — his way of paying music forward.

Dozens of other families around Phoenix have stories like Henderson’s. Many parents have seen their lives change as their young children succeeded through music therapy.

Before music therapy, Jim and Shelly Dilbeck say their son, JJ Dilbeck, was nearly kicked out of school for his aggressive behavior. After therapy, their son is less prone to lashing out and seems more peaceful. He now has hope that music might become a potential career path for her son.

"I see him take more interest in music," Shelly Dilbeck says. "I also see that he wants to do more. His behaviors have been really good as well, especially if it's all about music. He gets up in the morning to music and he goes to sleep with music."

Lilly Robles, meanwhile, was unaware of music therapy even after her own sister expressed interest in a local program. But her daughter, Abby Robles, eventually enrolled in ACCEL's program to deal with deficits in her communication and motor skills. While the child still experiences setbacks, there’s a larger success to celebrate.

"I've seen how she's made progress with it, and it's definitely given her more self confidence," Lilly Robles says. "She wants to explore different sides of music and sounds and instruments. She writes songs for her siblings now. We have five kiddos in the house, and everything is about music now.”

Other children, such as Jonah Miller, use music therapy to access music itself. His parents, Gina and AJ Miller, noticed him picking out harmonies on the piano when he was just a toddler. Over time, however, he came to use the piano to pound out his frustrations, bashing keys until they broke. Music therapy brought him back around to playing with joy, giving his parents a chance to connect with him.

"He is more interactive," Gina Miller says. "He understands more of what you're asking. It's helping to reintroduce his love of music.”

Results will vary among the kids and adults who try music therapy. Some will take to it like a wren to a ditty. Others will find it isn’t a panacea. But to cite one final example, there’s absolutely life-changing power in music.

Not long after Gabby Giffords survived a gunshot to the head, the former U.S. Representative enrolled in music therapy. In a November 2011 interview with ABC, Giffords' musical therapist, Meaghan Morrow, recounted that Giffords went from humming "Brown Eyed Girl" and "American Pie" to singing these songs outright in a few weeks.

"When I first saw Gabby and I first sang the song with her,” Morrow said at the time, “I knew that things were going to get better.”

‘The music actually drives the change’

Despite the everyday and high-profile wins for their profession, therapists still spend copious time explaining the basic aspects of their practices. Sometimes people simply confuse music therapy with music lessons. As Stewart explains: "We're focusing on what the music is going to do for you. And then, as a bonus, we get music out of it."Other times, though, this lack of understanding surfaces as misinformation. Therapists have found that people think they can act as their own musical therapist. When people lack clinical know-how, a DIY approach can have unpleasant consequences. Songs are tied inextricably to memories both specific and general. "This idea of just popping headsets on people, if you haven't really looked up the music, you can trigger a negative [reaction]," Oliver says.

A song that was merely popular during a traumatic time could thus be a landmine. Or a well-meaning gesture could be merely a gesture.

"It can be nice to play the harp when someone's dying, but YouTube needs to stop calling that 'music therapy,’” Kwok says. "In 13 states, you have to have licenses. With [neurologic music therapy], there's 29 standardized approaches, and they're all coming from a results-driven approach."

Musical therapists consider many layers of meaning for the approaches they bring to different treatments. With their training in neuroscience, Oliver says, therapists engaging music’s specific effects on a person’s brain. A singalong in a retirement home, for instance, may seem like fun to the participants, while the therapist is trying to optimize the neurological benefits.

"Some music therapists use music in therapy," Oliver says. "As neurologic music therapists, we use music as therapy. The music actually drives the change versus the music supporting somebody emotionally or recreationally."

There's nothing wrong with using music to aid in recovery and whatnot. Every person who enjoys music uses it, to some extent, as a mood regulator.

But patients must recognize the difference between self-help and actual therapy. In the latter, patients get support they're incapable of providing for themselves.

On that last point, Henderson has something to say. During the course of his ongoing music therapy "journey," the former pilot has worked with Stewart to craft a song that addresses his experience and encapsulates music therapy’s real-world effects.

One quietly heartbreaking line from "Lenny's Blues in A" speaks to how music can help overcome chasms of disconnect.

"I’m blue with a song I can’t sing/And I wrote it,” Henderson wrote. “I’m blue with a song I can’t sing/And I wrote it/The chords are hard, so is the tune."

The honor of experiencing art

A day after the community meeting at Central High, I caught up with Fray — just as she was coming off a job interview, no less. She said she remains "cautiously optimistic" about landing a music therapy gig at a private hospital.That's not to undercut her dignity-siphoning dismissal. She got the news of that capricious cut as she was at home caring for her husband, who was recovering from a surgery. Even if she can get reinstated at the VA, Fray might not return with the same parameters and freedoms.

Yet she wasn’t nearly as worried about the job search as she was for her former patients. She mentioned some who had started their own "therapy group" around a Spotify playlist. The one that seems to resonate loudest was a patient who she met as he was dying in hospice. In a darkened room, with so much life buzzing on the periphery, she picked up her guitar and played for him a beloved Bob Dylan tune.

Her soothing, nearly serene tone worked its way through new lyrics about peace and letting go. Each new note grew shorter, as if she was drawing the man's breath down to a slow, steady pace. Then, in an instant, he was gone. With the last notes, the room fell quiet.

"It was an honor," Fray said, with awe in her voice. "Art helped make us. It's part of the human experience."

Music therapy helps people get through their life. It connects hearts and literally changes minds. It empowers people to dismantle hardships, find strength, build joy and fully embrace their humanity. The lessons that music therapists provide are ones we desperately need now.