It worked with four local O’odham tribes on the name change and has plans to alter the logo, brochures, and signage before a grand reopening on October 9, Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Over time, plans are to redesign the exhibits as well.

When white people created the museum, they didn’t ask any of the descendants of the area’s original inhabitants what they wanted to call it, and the name stuck for over 90 years. “Pueblo” means town or village in Spanish and reflects a language with no connection to the people.

S’edav Va’aki is pronounced “suh-UH-dahf VAH-ah-kee” and is an O’odham name for the large central (S’edav) platform mound (Va’aki) that was the ceremonial house of a village in the Salt River Valley. This archaeological site is also integral to understanding the vital canal system that was built and maintained with stone tools and helped the community thrive for so long.

“We want to talk about that continuing connection between the ancestors and the current O’odham community,” says Nicole Armstrong-Best, museum administrator. “They have stories about this village. They feel the Va’aki is sacred. So we want to honor that and interpret that with them so that our visitors understand that the Hohokam did not disappear in 1450. They changed the way they lived on the land, but they’re still here.”

In 1924, Phoenix was the first American city to hire an archaeologist, Odd Halseth, who built the museum. It opened in 1929.

Artifacts from the site reveal that the entire village extended east to west from what is now roughly South 44th to 48th streets and from East Van Buren Street on the north to the Salt River bottom on the south. It included houses, farm fields, lateral canals and more, but archaeologists have only preserved small pieces of it.

Oral traditions passed down among the tribes correlate with artifacts found in the area. But during the process of meeting with tribes and creating exhibits with them, Armstrong-Best says, “Their feeling about being erased from their own homeland has come across very strongly, so we felt we needed to do something about that.”

S'edav Va'aki Museum Administrator Nicole Armstrong-Best stands near the platform mound and new signage that's been installed.

Geri Koeppel

She and the museum staff worked with the Salt River Pima Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC), Gila River Indian Community, Ak-Chin Indian Community, and Tohono O’odham Nation so they would have more input on how the site is interpreted. The name change grew out of that cooperation.

One important facet to note is that Hohokam and Huhugam are different concepts. Hohokam is the archaeological term for people who lived here and left artifacts behind. It’s based on the word Huhugam, which is the O’odham word for “ancestor.”

But the Huhugam didn’t simply vanish mysteriously, as popular but incorrect lore has taught: Tribes today are associated with people that lived here starting in 1 A.D. Adding that context will be integral to the museum’s transformation.

It already has changed out signage on the one-kilometer trail around the premises and hired an O’odham artist, Jacob Butler, a councilman for SRPMIC, to redesign the logo. The website is under construction as well with new pathways reflecting the name change.

Currently, the museum comprises four galleries. The main room follows a timeline from 450 to 1450 A.D. and covers the region’s land and people. Another gallery has an exhibit of stylized Zuni maps because they and the Hopi also claim connections to the site. “Zuni have stories about migrating south and the Hopi have stories about migrating north,” Armstrong-Best says.

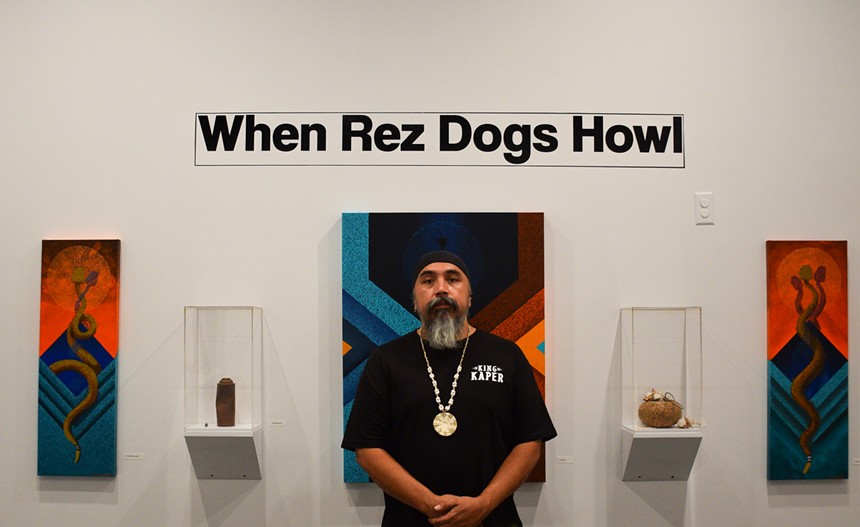

Thomas "Breeze" Marcus poses with his exhibit, "When Rez Dogs Howl," on display through May 14 at S’edav Va’aki Museum.

S’edav Va’aki Museum

The kids’ gallery teaches about archaeology in general and has activity stations, and a fourth gallery is for rotating exhibits. The current one, “When Rez Dogs Howl” by Thomas “Breeze” Marcus, is up through May 14, and the works are available for purchase.

“We want to make sure that we include contemporary themes and we make that connection to contemporary O’odham,” Armstrong-Best notes.

Breeze — who explains his tribal affiliation is “Tohono O’odham by way of the Salt River Pima Maricopa Community” — says his bold, geometric paintings are a mixture of contemporary personal experiences, but they take inspiration from the traditional sense of place and culture.

“When people think of the Valley, they think of history as 100, 150 years — not 1,000 to 2,000 years and beyond,” he states. “The artwork is meant to be a continuum of that long legacy in a contemporary way.”

Breeze started as a graffiti artist and says he has come to understand his place in art history and the fact that graffiti is a way to communicate in a public space. “Whether it’s hieroglyphics on pyramids in Egypt or on Mayan pyramids or on rocks here in the Valley, the way to communicate with each other in that way is hard-wired,” he says.

However, Breeze adds, “In growing over the years you start to find deeper meaning in what you convey.” He’s committed to expressing ideas representing the past, present, and future.

And he’s glad for the changes coming to S’edav Va’aki. “Museums — not just this particular museum, but all museums — experience needing those updates so they’re not becoming stagnant and losing interest or only catering to a certain demographic,” Breeze says. “I think it’s important for places like that to not only be updated but tell accurate narratives and have [the] inclusion of other really rich in-depth information that I think could be provided.”

Armstrong-Best also is excited about the upgrades. SRPMIC provided a grant to S’edav Va’aki to create a plan, which she hopes will be finished late this year, for redesigning the galleries. After that, the museum will raise money from the city and donors to implement the plan.

There’s a lot of work to be done, Armstrong-Best says, adding that she wants to introduce visitors “to the fact that there are living tribes here and there are tribes associated with these prehistoric villages.”

S’edav Va’aki Museum is located at 4619 East Washington Street. Summer hours are 9 a.m. to 4:45 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday. Admission is $6 adults, $5 seniors and $3 students. Call 602-495-0901 or visit the museum's website for more information.