Just a day after the 2018 elections, activist, musician, and now film director Boots Riley is seeing more proof that Americans are ready for socialism. For that, he says, look no further than the defeat of Democratic Representative Joe Crowley of New York by the 29-year-old Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

"There’s candidates coming out like what’s-her-name, Ocasio-Cortez, in New York, coming out and saying she’s a socialist, and coming out and making way more people vote for her even though the dude has way more money to spend!" he says. "Because it didn’t matter no matter how much the other person spent. She was saying something that people actually agree with."

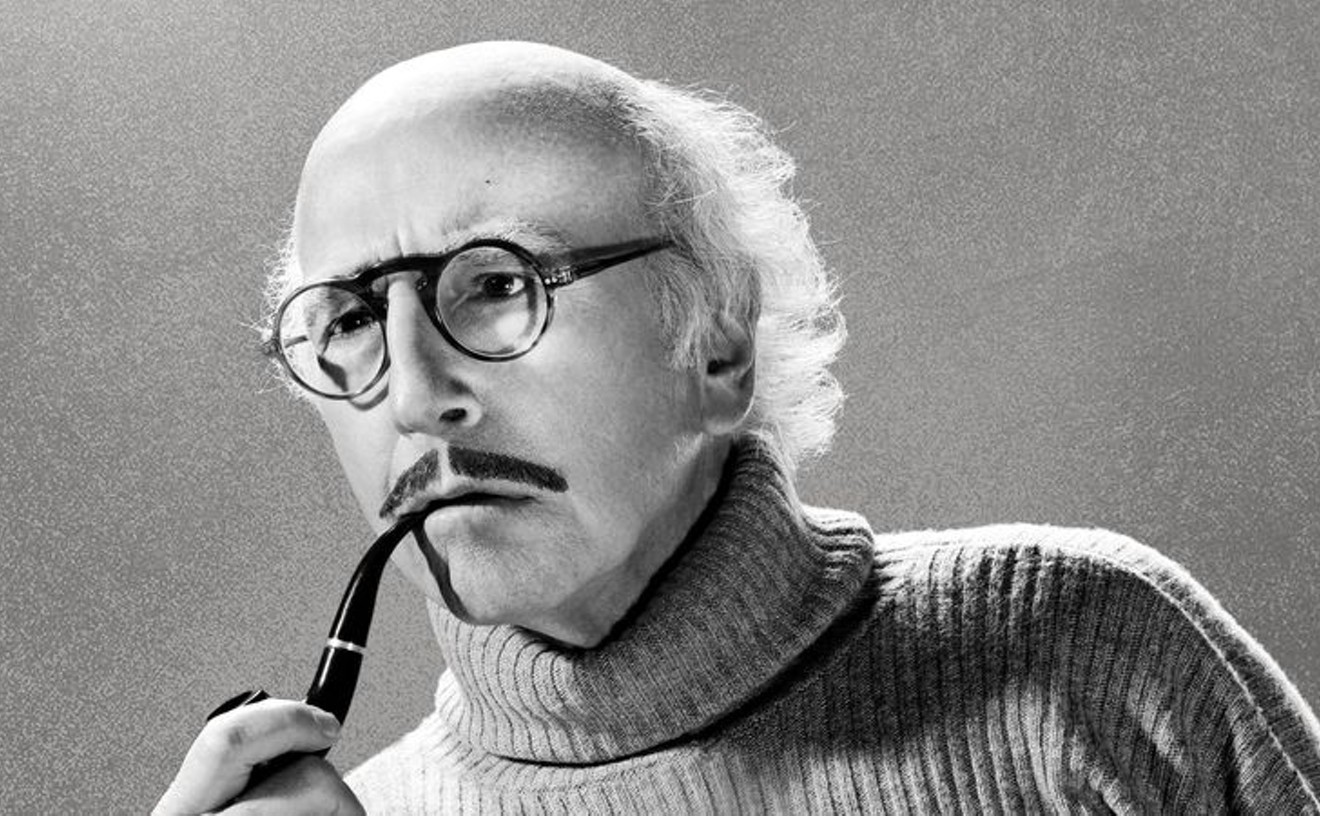

For years, the Oakland, California-based Riley has identified as a communist, a label he's kept even while promoting his new film, Sorry to Bother You. A leftist activist since his teens, he's channeled his potent beliefs into the movie, about a black telemarketer (Lakeith Stanfield) who uses his "white voice" to climb the corporate ladder just as union activities boil over below. It isn't just the most politically radical film to come out of Hollywood in years, but also a colorful, surreal adventure into the dark heart of American corporate greed, a Network for the Amazon age with a psychedelic edge.

Riley will be discussing the film following a screening at Arizona State University's Sun Devil Stadium this Wednesday, November 14, at 7 p.m. Phoenix New Times caught up with the director last week and got his thoughts on politics, art, and life's contradictions.

This interview has been edited for length and content.

Phoenix New Times: Do you think the potential for socialism and communism to take hold in America is stronger now?

Boots Riley: I think it’s more openly talked-about now. I think that has nothing to do with the elections, but you put it like this: A lot of these places that are considered red states right now – and there are a whole bunch of people that are to the left of both these parties that are not speaking their mind – but even in those red states there are people that are to the left of both parties that we’re not counting, just because it’s inconvenient to talk about. They get summed up as “apathetic,” but it’s not true. It’s not that they’re apathetic, they just don’t trust either party. That’s different. They want something different. They want things to change; they just have no faith in that electoral process.

I think a lot of things get really skewed. One time I was on an airplane while Obama was in office, and there were these two older ladies talking to each other. And they identified, through what they had said, I knew that they were Republicans. But they were like, “You know, I’m really not okay with this Obama character, he’s trying to take us to the days of socialism! We don’t want that, this is America!” Something like that. And then, immediately, the next sentence was “What they need to do is get these banks that stole all our money pay directly for our health care and give it to all of us for free!” Now, these are Republicans, and what they said is way more radical than Obama’s health care plan.

The point is that the politics of some people is like tribalism: “This is what my family believes.” Certain keywords. For instance, if I say the phrase – and I say it often – which is that the people should have democratic control over the wealth that we create with our labor, very few people can or will disagree with that. Some people will. But most people will say, “That makes sense.” But if you were then to tell them that that means socialism or communism, they might then think of all the propaganda from all the movies they’ve seen about why that won’t pass, that can’t happen, and all that kind of stuff. So I think more people are seeing through the bullshit and understand that the real two camps are the working class – and it does have divisions, there’s racism in between that – but it’s the working class struggling against the ruling class, folks that own all the companies, that own most of the land, that own all of that.

You wrote the film in 2012 and originally released it as an album with your band, The Coup. What was involved with getting it made and how difficult was it to get made?

Well, as you say there it took like six, seven years to get made. One was getting over the hump of me being a musician with a script, which I thought would help me, but who wants to read that? Getting some folks to cosign it once I finally got people to read it, going person by person for people to be like, “Oh, I like this.” The first people to sign on were David Cross and Patton Oswalt when I had no producers, no money, nothing, and it at least let people know, “Oh, maybe this is funny.” But their names weren’t enough to fund the whole movie. Once I joined SFFILM (the San Francisco International Film Festival) and got a grant from them, that further cosigned things for me. Then Sundance was the biggest cosign. I got accepted into the Sundance Writers Lab, then the next year after that – I’m skipping a bit – I ran into Dave Eggers from McSweeneys, and he read it and went around said it was the best unpublished screenplay he had ever read and published it as its own paperback book in McSweeneys, which is kind of – I’m not using this word pejoratively, but a hipster publication, a hipster publishing house. They sent out like 10,000 or 20,000 copies packaged with the McSweeneys quarterly. So that was a big thing. Then I joined the Sundance Directors Lab the next year. And this whole time, it’s more about convincing people it will work. Because the script is so out there, the script is so crazy.

So much of any industry is, “Let’s do what worked last year.” So all of a sudden, because Sorry to Bother You was so successful, right now in meetings in the film industry there’s a bunch of people pitching their project about how it’s like Sorry to Bother You. That’s no fault on them, but they know how the industry works. And so when you have something where you can’t really say it’s like this, or it’s like that, then that becomes a problem. So that was my biggest problem. It didn’t have anything to do with the politics, it had to do with the crazy storyline.

There’s a very funny, surreal scene in the film where the main character, Cassius, is at a party full of white people who coerce him into performing a “rap,” and the only way he can get a positive response is by shouting the n-word at the crowd. Is that scene drawn from personal experience? Have you ever had to perform your race in that way?

I think it’s something that can go on unconsciously with folks. I mean, it’s not dissimilar to people that have moved from New York to Arizona, and they become “Mr. New York.” They’re talking about how New York is, their accent is thicker than it was in New York, that sort of thing. They represent that for folks, and I think with race it can become that way sometimes. There’s qualities that are essentialized and exaggerated. People realize that, in certain situations, they’re asked to be the token in some way, and it may not be as literal as in the scene that I put forth, but I think that situation happens all the time. And a lot of the things in my film, I think there’s ways to talk about it because of my political ideas, but I think that everybody in my film has contradictions. And I put them all out there not necessarily in judgment but just in showing how life works, in showing what contradictions there are. There are some things that I have, some overarching things that I feel strongly about, but I’m more talking about how these overarching things affect how we relate to one another, and some of the things that we don’t necessarily think about.

Do you think those contradictions are necessary for getting along in life?

I don’t know if they’re necessary to get along, I can’t say that, but I think that they are there, that’s how we work through things. All life is just contradictions, ideas pushing against each other which form new ideas. I think it’s forces that want one thing versus forces that want another thing, and some sort of result coming out of that. Tension. And it’s like that in peoples’ heads as well. And for me, putting those contradictions in there was about writing about things in a more realistic way.

The art direction in the film was very strong. I have a friend who told me he knew nothing about the film and saw it because he thought the colors on the poster were interesting.

I put it like this: Aesthetics are very important, and we had the font for the movie before we had the cast and before we had money. Because all of those things are really important to me. We had an amazing production staff. First, the guy who did the lettering and the fonts was my longtime friend J. Otto Seibold, who does children’s books and all that kind of stuff. So that’s part of juxtaposing that optimism with the harsh realities of life and horrible things going on, to me it’s part of the contradictions that are out there. The way we presented this, with the graphic design and the production design, is a big part of the whole concept to me.

We had an amazing production designer named Jason Kisvarday, who’s most famous for the “Turn Down For What” video. And he and I met over spaghetti and really saw kindred spirits in each other, and we went for this “beautiful clutter” aesthetic that I had in mind based on this photo I saw of Bob Marley’s bedroom that I saw, from when he was a teenager. And we built out from that.

For me, everything is important. Everything is a chance, from the colors, to the camera placement, to everything. Obviously, I get the people around me that are skilled at these things, at helping me get my idea into reality, but every aspect is a chance for me to say something, just to say something about life, from the composition to the colors to the production design to the costume design. We had amazing people on board.

I think maybe there are some films that I love watching where the whole idea of the production design is just to make it look real. That’s not the kind of film I wanted to make. It does look real, but there are things that we’re doing to you, that we’re purposely doing to you through it that make if “off” just enough for your mind to engage more with it.

Hollywood Invades Tempe: Sorry to Bother You. 7 p.m. Wednesday, November 14, at Sun Devil Stadium, 500 East Veterans Way, Tempe; asu365communityunion.com. Tickets are free for ASU students and $3 for the public via Ticketmaster.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]