The response from the Grand Canyon Trust was immediate: See you in court.

The Flagstaff-based organization blasted Trump’s December 4 proclamation, which drastically reduced the size of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante.

“President Trump’s attack on our national monuments represents the most drastic assault on protected public lands in American history,” the Trust said in a release. “It is an attempt to tear down the legacy of his predecessors while deeply dishonoring Native Americans at the expense of future generations.”

It was just the latest example of the Trust standing up to the Trump administration, which conservationists say has begun an industry-led assault on public lands. That means that the organization’s new executive director, 43-year-old Ethan Aumack, will have his work cut out for him.

On January 1, Auback took over the advocacy group that was founded in 1985 to protect and restore the Colorado Plateau and other public lands in the Southwest.

His immediate aim is simple: “I would say our primary goal is ensuring that we don’t lose as much as we could during the Trump administration."

“The policies being put forward by this administration — it would be an understatement to say they are antagonistic to the environment,” Aumack told Phoenix New Times. “They’re really unprecedented in their unfriendliness.”

Aumack's roots are in Arizona.

His family moved to Flagstaff from Eugene, Oregon, when he was 5. The son of a public defender and a behavioral psychologist fell in love with Arizona as a teenager, he says. After a stint studying biology at Swarthmore College on the East Coast, Aumack felt he had to return. “I missed the West tremendously,” Aumack said.

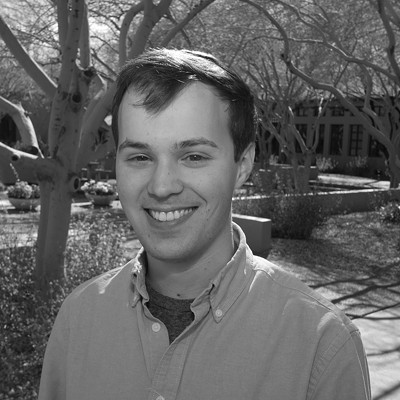

Grand Canyon Trust executive director Ethan Aumack in the backyard of the nonprofit's office in Flagstaff.

Joseph Flaherty

Aumack went to school down the road from the Grand Canyon Trust building, which occupies an antique 1920 Flagstaff homestead made of dark wood. “It’s not the most energy-efficient building,” Aumack said sheepishly on the way up a flight of stairs.

Some of the organization’s 31 staffers were working on Monday: friendly, outdoorsy types. Aumack has a small, attic-like office, the walls adorned with paintings.

Grand Canyon National Park will celebrate its 100th birthday next year. But from Aumack’s perspective, public lands like the Grand Canyon are at risk like never before. “It’s been a bit of a shock-and-awe year for us,” he said. “We’ve been working defensively on more fronts than we ever have in the past.”

Financially, the organization is on solid footing for its advocacy work. The nonprofit’s coffers have grown over the past few years, according to its IRS filings. In 2016, the Trust raised over $5.4 million from contributions and grants.

When Trump won, Aumack described it as “gut-check time.” Yet during the presidential transition, Aumack and others weighed how Ryan Zinke might run Trump’s Interior Department, or if Zinke would “be one of the more moderate voices on Trump’s cabinet.”

That didn’t happen. In response to an April executive order, Zinke put together what Aumack calls a “hit list” of other monuments on the table for evaluation. Four of them are in Arizona.

And last month, Trump attempted to reduce the two monuments in Utah. But the Trust, the Sierra Club, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and other environmental groups argue in their lawsuit that by slashing the monuments, the president overstepped his authority. The 1906 Antiquities Act gives the president the power to create monuments, not to “abolish them either in whole or in part,” they write in the complaint.

The way that Aumack sees it, the lawsuit's stakes are high. If the Trust loses its fight to preserve Bears Ears and Grand Staircase, what happened to those monuments in Utah could happen to Arizona's monuments, including Grand Canyon-Parashant, Vermillion Cliffs, Agua Fria, and Ironwood Forest. “We don’t think the president is done yet,” Aumack said.

In response, the Trust is in a two-front war, playing defense on monuments and public lands through litigation in the short-term, while attempting to build public support and develop sustainable land-use policy in the long term.

“I think the Trump phenomenon is a temporary, disturbing one,” Aumack said, “but we’re going to see folks push back, and push back hard.”

Last year, the Trust along with other organizations sued the Interior Department and two other federal bodies for not responding to Freedom of Information requests related to the monument review. And in another FOIA battle, the Trust individually sued Zinke and the Bureau of Land Management for not releasing records about the environmental impact assessment of a coal program.

But as one fight happens, like the lawsuits on Bears Ears or FOIA, other environmental concerns loom down the road. In a recent report from the U.S. Forest Service, the Trump administration opened the door to renewed uranium mining in the Grand Canyon region. The Obama administration had put new mining claims on hold in 2012.

Even as the Trust celebrated a victory last month when the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Obama's mining ban, the provisional report shows that progress doesn't last forever. (A Forest Service spokesperson told New Times in November that at this time "there is no plan" to restart uranium mining on public land surrounding the Grand Canyon.)

When asked whether it’s hard to stay optimistic in the face of environmental rollback, Aumack said, “It feels dark at times.” Nevertheless, for him the moment feels energizing — in a calamitous sort of way.

“We’ve seen a groundswell of support for the protection of public lands and places people care about, more so than I have ever seen in 20 years,” Aumack said. He added, “And I think we’re going to win the day.”