Patterson Park stretches for 16 blocks among the rowhouses in southeast Baltimore’s waterfront neighborhoods. The urban park is a familiar sight for city dwellers. Stroll through the open space and you’ll see dog-walkers circling an artificial lake or yuppies practicing their downward dog near a towering pagoda.

The area wasn’t always prime real estate for upwardly mobile 20- and 30-somethings. In the 1970s and ’80s, manufacturing jobs that were once the heartbeat of Baltimore’s economy began drying up and drugs started flowing in.

Prostitution also flourished. Patterson Park became a hub for young boys selling sex acts for drug money. Men, known as “chicken hawks,” cruised the area looking to shell out $5 or $10 for a few minutes of sexual activity with minors. The boys, known as “chickens,” stood on street corners flashing hand signals to let passing motorists know that they “hustled.”

Rafael Alvarez, a former Baltimore Sun reporter who worked on the paper’s city desk in the ’80s, covered a neighborhood campaign to stem the epidemic of adolescents selling sex near Patterson Park. Social workers pushed for more tutoring and recreational programs for the youth. They also advocated for treatment for the oft-disadvantaged children.

“Chicken-hawking was characteristically a white, poor-to-working class phenomenon among the” boys, Alvarez told Phoenix New Times, describing the blocks surrounding the Patterson Park of the ’80s as an “open-air pedophile market.”

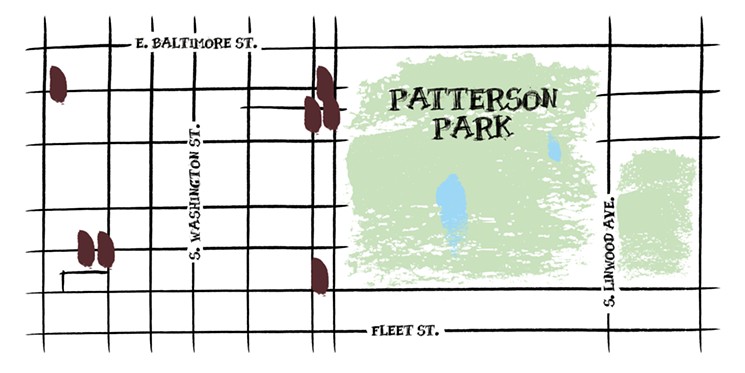

It was during this era that a 35-year-old federal employee named David Henry Stringer owned or took out mortgages on several properties within walking distance of Patterson Park, according to Maryland land records.

There was 1722 Portugal Street, about 11 blocks west of the park. There was 422 and 420 South Ann Street, which shared a block with the property on Portugal Street. And there was 1740 Eastern Avenue, the address listed on Stringer’s 1983 Maryland court case history for five sex offenses.

David Stringer owned multiple properties near Patterson Park, known in the '80s as a hub for the underage sex trade.

Lindsey Kelly

By now, most Arizona Capitol watchers are familiar with the accusations against Stringer — denied by him — that roiled the 2019 legislative session and ended the lawmaker’s political career last month.

In August 1983, Baltimore detectives interviewed a boy who said Stringer paid him $10 for sex, including oral sex and “sodomy,” multiple times over the course of a year, police reports show. The boy, who was 15 at the time, said he met “Mr. Dave” in Patterson Park.

The alleged victim said Stringer also sexually assaulted another boy, who was 13 years old, at Stringer’s apartment. One of the boys — it’s unclear from records which one — had an intellectual disability, according to police reports.

In September 1983, Baltimore police detective Ed Paugh arrested Stringer on suspicion of sexually assaulting the two children, according to reports released in March by the Arizona House of Representatives Ethics Committee.

The next year, Stringer entered into a plea agreement on his sex charges. Baltimore Circuit Court Judge Robert Hammerman sentenced him to five years’ probation and ordered him to seek treatment at a well-known clinic for sex offenders, Stringer’s case history shows.

Stringer likely thought his criminal history would stay buried forever. The Maryland judiciary expunged his case in 1990, effectively erasing his charges from the public record, as a condition of his sentence.

For the next 28 years, Stringer followed a career path suited for elected office.

He defended indigent clients as an attorney in Washington, D.C., and Maryland courts. He purchased a Comfort Inn in Prescott. He invested in Prescott eNews, an online news organization with a conservative spin. He attended graduate school at Arizona State University, seeking a master’s degree in teaching English as a second language. He served on city committees and nonprofit boards, including the panel overseeing Yavapai Big Brothers and Big Sisters.

In 2016, Stringer ran for the Arizona Legislature as a Republican on a platform of small government, curbing illegal immigration, and criminal justice reform. He won his District 1 seat representing Yavapai County, and he might have had a long political career.

If he just hadn’t started talking about race.

"Ridiculous comments"

David Schapira recalls sitting in a passenger seat in June, driving to a campaign event for the state superintendent’s race, when he saw the Facebook video of Stringer calling immigration an “existential threat.” Schapira’s friend sent him the clip, pointing out some pretty “ridiculous comments” in the hourlong footage from the Yavapai County Republican Men’s Forum.Schapira already didn’t think much of Stringer. The two had met previously at a Yavapai County debate, where Stringer told him no Democrat had a chance of winning the superintendent’s race. (Schapira lost the Democratic primary to Kathy Hoffman, who went on to win the superintendent’s race.)

Schapira, however, wasn’t prepared for what he was about to see in the cellphone video posted on Stringer’s campaign Facebook page.

Stringer stood before Arizona and American flags. Glassware clinked in the background while Stringer ranted against immigration, specifically immigration from people of color. Near the end of his speech, Stringer expressed a Eurocentric vision of the country and skepticism of assimilation.

“If we don’t do something about immigration very, very soon, the demographics of our country will be irrevocably changed and we will be a very different country. It will not be the country you were born into,” Stringer said in the video.

He then turned to a dire warning about the state’s education system: “60 percent of public school children in the state of Arizona today are minorities. That complicates racial integration because there aren’t enough white kids to go around.”

Schapira was disgusted by Stringer’s comments. He downloaded Stringer’s full speech, created a two-minute clip of his comments on immigration, and tweeted the clip on June 12 with commentary: “An AZ legislator made these overtly racist comments about our students. It’s time to remove xenophobic radicals from elected office this November!”

Stringer’s campaign removed the video from his Facebook page soon after Schapira’s tweet, but that didn’t stop his views on immigration from going viral. New Times covered Stringer’s comments. So did the Arizona Republic and 12News. BuzzFeed News, CNN, and the Washington Post followed.

Stringer’s remarks were promptly met with widespread condemnation. Democrats pounced. Governor Doug Ducey, a Republican, and Arizona Republican Chairman Jonathan Lines called for Stringer to resign.

Stringer refused, saying in a Facebook post that he would not give in to “conservative bigwigs” or “liberal bullies.”

On June 27, Stringer appeared at Lo-Lo’s Chicken & Waffles with the controversial activist Jarrett Maupin, who had told reporters that Stringer planned to issue a public apology for his “offensive, bombastic, and ill-conceived remarks.”

Former New Times writer Antonia Noori Farzan captured the ludicrousness of the spectacle: “No lunch was served until after the hour-and-a-half-long forum had ended and the reporters had left, and not many black and Latino leaders were present. The handful of community members who showed up got only a halfhearted apology from Stringer once he finally did arrive.”

Stringer did not apologize specifically for his comments, but “for anyone who was offended” by them. He then struggled to answer questions on whether he considers himself a white nationalist.

Despite the bipartisan disapproval, Stringer maintained some key supporters, including the National Rifle Association and the Center for Arizona Policy, the influential lobbying group whose mission statement is “to promote and defend the foundational values of life, marriage and family, and religious freedom.”

Stringer won re-election, earning twice as many votes as Democrat Jan Manolis, on November 6, 2018.

State Rep. David Stringer struggled apologize for racist statements at Lo-Lo's Chicken & Waffles.

Antonia Noori Farzan

Don't blend in

On November 19, ASU sophomore Stephen Chmura attended a lecture by political history professor Don Critchlow. The political science major went for extra credit. Stringer also attended the lecture, which covered the Republican Party’s losses in the 2018 midterm elections. During a question-and-answer session with Professor Critchlow, Stringer commented that Hispanic voters present a challenge for Republicans.

“The Hispanics, even middle-class Hispanics, they vote Democratic because the number-one issue is immigration and bringing more — they’re coreligionist — bringing more people like them into the country,” he said.

Chmura and a classmate, Sam Thiele, researched the lawmaker on their smartphones and came across his June comments on immigration.

When the lecture concluded, Chmura and Thiele walked into the same elevator as Stringer, who engaged them in conversation. The discussion continued outside the lecture hall. Thiele began recording the exchange, which turned into a debate on multiculturalism and assimilation.

Stringer asserted that “diversity in our country is relatively new,” to which Chmura responded by noting early immigration to the United States from Ireland and Italy.

“They were all Europeans,” Stringer said. “By the second and third generation, everybody looks the same, everybody talks the same, but that’s not the case with African-Americans or other racial groups because they don’t melt in. They don’t blend in. They always look different.”

“Why does looking different matter?” Chmura asked.

“I don’t know. Maybe it doesn’t. Maybe it doesn’t to a lot of people. It seems to matter to a lot of people who move out of Detroit, who move out of Baltimore. You know we have white flight in this country,” Stringer responded.

He mentioned Arizona’s large Spanish-speaking population, claiming it produces “tensions” and “burdens on our systems.”

Chmura interjected, “I just don’t see the difference between my great-grandfather, who’s a Polish immigrant wanting a better life, and somebody from Venezuela, who wants to escape a socialist regime.”

“I don’t see a big difference either,” Stringer said. “I mean you’re coming here for similar purposes. I think that’s true.”

“There were ethnic issues for the Polish immigrant — who was called a Polack, they were discriminated against but they assimilated,” Chmura said.

“The difference between the Polack — I shouldn’t say Polack. You said Polack, but I shouldn’t say Polack — The difference between the Polish-American immigrant and the immigrant from say, Somalia, is the second-generation Polish immigrant looks like the Irish kid and the German kid and every other kid, but the immigrant from Somalia does not.”

“Does that matter?” Chmura asked.

“I don’t know,” Stringer said. “I honestly don’t know.”

New Times obtained Thiele’s recording through a third party and published a story on Stringer’s comments on November 30, 2018.

Stringer’s remarks sparked a new wave of condemnations. Ducey and Lines renewed their calls for him to resign. The Yavapai County Bar Association rejected Stringer’s application to renew his membership, and the Prescott City Council voted for a resolution calling on him to step down. Schools banned him.

Democratic co-whip State Representative Reginald Bolding was one of the most outspoken critics. He told 12News’ Brahm Resnik that his party would attempt to expel the Prescott lawmaker if he brought that “toxicity” to the Capitol.

Bolding later told New Times about Stringer’s comments, “I thought it was offensive. I thought it was offensive to me, I thought it was offensive to my coworkers and colleagues down here who are African-American. Even more so, I thought about the young men and women, boys and girls, who look up to elected officials.”

Stringer faced new consequences in the House, too. Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers removed Stringer from the House Judiciary Committee and House Education Committee. Bowers also dissolved a newly formed House Sentencing Committee that Stringer was tapped to chair.

Stringer still had defenders.

His seatmate State Representative Noel Campbell wrote an opinion piece for Prescott eNews — a site partially owned by Stringer — attacking the ASU students for recording their conversation with Stringer and suggesting that calls for his resignation represented an “attack on our First Amendment rights.”

The Tucson conservative commentator James T. Harris invited Stringer onto his radio show and scolded him for speaking freely about his ideas on race, thereby jeopardizing criminal justice reform efforts in the legislature.

“My point to you is: Do you not understand how even going into this conversation on a liberal college campus is beyond the dumb-dumb?” Harris said on his 550 KFYI program, Conservative Circus, on December 4, 2018.

“I’ve resolved not to talk about these issues any more,” Stringer said.

Stringer also appeared to run his own campaign to restore his image.

On January 20, Stringer wrote a Facebook post celebrating Martin Luther King Jr. Day, praising the civil rights activist’s “uncompromising embrace of nonviolence.” Stringer paid Facebook to boost his post, records show.

Three days later, Stringer issued an apology on the House floor to his colleagues, legislative staff, and Bowers that did not specifically address his comments.

“I would never intentionally say or do anything that would make you doubt my respect for you, or make you feel uncomfortable working with me,” Stringer said. “Issues that relate to race and ethnicity are very sensitive in any setting.”

Racists, meanwhile, celebrated Stringer’s remarks. According to chat logs leaked by the independent media organization Unicorn Riot, which were picked up by AZMirror.com, members of the white supremacist group Identity Evropa approvingly circulated links to Stringer’s comments.

As someone who went by the username PatrickAZ wrote on December 14, “This is one of my representatives. Want to talk with this guy. He seems /ourguy/.”

Someone else had also read Stringer’s remarks.

Anonymous tip

Not long after Chmura’s audio became public, New Times heard from a tipster who was familiar with a David Stringer when he lived in Baltimore in the ’70s and ’80s.The tipster had read about State Representative Stringer’s ASU comments in news reports, and the lawmaker’s name immediately jumped off the page. His photo — gracing front pages and online stories — also bore a resemblance to the man who lived in Baltimore four decades ago.

If State Representative David Stringer was the same David Stringer the tipster knew, then the Arizona lawmaker was involved in serious criminal activity many years ago, the letter stated. The tipster urged New Times to check Maryland court records for more information.

On December 18, an employee of the court handed Lawrence Lanahan, a reporter working on New Times’ behalf, a copy of a microfiche case history showing five sex-offense charges Stringer faced in 1983.

Over the next month, Stringer did not respond to multiple emails and phone calls from New Times requesting comment. He also declined to comment on January 15 when confronted about his Maryland criminal case by this reporter on the House floor.

The next day — on January 16 — the conservative site Arizona Daily Independent published the first story about Stringer’s 1983 charges, headlined “David Stringer’s False Arrest Drives Empathy For Those Trapped in Unfair System.”

The one-sided article, written by Loretta Hunnicutt, claimed Stringer was falsely arrested for “possession of pornography and patronizing prostitutes.” Two “prostitutes,” Hunnicutt wrote, gave up Stringer’s name in exchange for leniency with prosecutors. As for the “pornography” charge, the article claims police searched Stringer’s home on the day of his arrest but found none.

Hunnicutt’s story claimed that Stringer’s attorney at the time — listed on his case history as Nathan Stern — estimated that he had an 85 to 95 percent chance of beating his case. But Stringer did not want to take his chances, the article claimed, and he pleaded to “probation before judgment” on two misdemeanors. Losing his case would mean the end of his government job and legal career.

“On the other hand, the state clearly wanted to end the matter that day, and taking the deal meant Stringer would be allowed to maintain his plea of not guilty, there would be no conviction on his record, and the matter would be expunged,” Hunnicutt wrote.

The article appears to have been a pre-emptive defense against an upcoming New Times story. Stringer later denied to Arizona Capitol Media’s Howard Fischer that he was the source of the article, despite the fact that Hunnicutt had written that “Stringer came to us with the story.”

“Questions he received from a reporter made it pretty obvious they were preparing a hatchet job on him,” Hunnicutt wrote.

Stringer posted a link to Hunnicutt’s story on his Facebook page, making no mention of his charges. No other media picked up the article.

New Times published its story revealing Stringer’s 1983 court case on January 25 with the headline, “State Rep. David Stringer Charged With Child Porn in 1983, Court Records Show.”

Ethics investigation

Republican State Representative T.J. Shope remembered being in Tucson for his other job as a sales development officer with the National Bank of Arizona when the news of Stringer’s charges broke. He read the New Times story, as well as the Arizona Daily Independent article, which he called a “rebuttal.”As the Chairman of the House Ethics Committee, Shope figured that Stringer’s Maryland court case would wind up on his desk in the form of a complaint. “My wheels were moving there,” he said in an interview.

The role of the Ethics Committee is not to make a legal ruling of guilt or innocence for an individual, Shope noted, but to determine whether certain behaviors could violate House rules. In Stringer’s case, Shope felt that lawmakers would probably file complaints referencing a rule against “conduct unbecoming.”

On the other side of the aisle, House Democrats had already been planning action against Stringer over his racist comments. Bolding recalled that he and his colleagues debated whether to push for expulsion or censure over Stringer’s November remarks to ASU students, and appeared to be leaning toward censure when the legislative session began in January.

The revelation of the 1983 charges pushed the Democrats to demand expulsion, and Bolding made the motion to kick Stringer out of office on January 28.

“I don’t know what happened in 1983,” Representative Bolding said on the House floor. “But I can tell you that allegations of a sexual nature that was not disclosed to the body, to our voters, that is not transparency.”

House Speaker Rusty Bowers argued that Stringer’s case should undergo the scrutiny of the House Ethics Committee before the legislators made any decisions on his fate. Bowers invoked the February 2018 expulsion of former State Representative Don Shooter. Shooter was ousted by his colleagues over sexual harassment allegations without a chance to argue his side of the story before the Ethics Committee. He later filed a lawsuit against the Legislature on January 30 over his expulsion, claiming due-process violations.

Bowers said Shooter’s saga led legislators to decide that, “in the future, there would be a method to address these issues as they come — heinous, unacceptable, however we might describe them — but there still was a process.”

House Republicans voted to adjourn before taking up Bolding’s expulsion motion.

The complaints against Stringer were filed within the next couple days: One came from Bolding, the other from State Representative Kelly Townsend, a Republican from Mesa. Bolding’s complaint covered Stringer’s racist comments and sex charges, while Townsend’s focused solely on the latter.

On January 4, Ethics chairman Shope hired Joe Kanefield — a constitutional attorney with the firm Ballard Spahr — to conduct the investigation into Bolding and Townsend’s complaints. Kanefield had previously served as general counsel to Governor Jan Brewer, state elections director for the Secretary of State’s office, and several other high-level positions in state government.

Shope said he picked Kanefield because he felt that his investigative team was “top notch,” citing the fact that some of the firm’s attorneys had formerly worked as prosecutors. Kanefield, who declined to comment for this story, got right to work.

Joe Kanefield (left) and T.J. Shope (right) confer outside a Maricopa County courthouse moments before David Stringer resigned.

Steven Hsieh

Sealed letter

During the two-month ethics investigation, Stringer made it clear that, if Kanefield and his team wanted information on his Maryland court case, they wouldn’t get it from him. Stringer hired Carmen Chenal, a former state Assistant Attorney General, to handle his defense. Letters and emails between Chenal and Kanefield — which were released by the House Ethics Committee — show their relationship deteriorated through the course of the investigation.

On February 28, Chenal falsely argued that Stringer himself would be violating Maryland law if he were to disclose his expunged records, adding that the state’s usual practice is to destroy such records after three years.

She separately disclosed that the District of Columbia Office of Bar Counsel provided her a letter from 1984 that dismissed a complaint against Stringer related to his sex charges. According to Chenal, the letter said the Bar was led “to the conclusion that there was no involvement of moral turpitude such as would adversely affect [Stringer’s] fitness to practice law.”

Kanefield responded on March 4 that Maryland law allows for an individual to ask state courts to open an expunged record, which could include police investigation reports.

On March 14, a separate investigation into Stringer by the Arizona State Bar found that there was insufficient evidence to determine whether he violated any rules related to disclosing his criminal charges when he applied to practice law in this state in 2004. His application, following standard practice, had been destroyed years before.

Chenal on March 15 sent another letter to Kanefield asserting that the Arizona Bar’s decision should lead the Ethics Committee to dismiss the investigation of Stringer.

“It is difficult to imagine an investigation more unjustified and unfair to Rep. Stringer, to taxpayers and to the people who elected Rep. Stringer than to ask him to address an issue that was resolved more than 30 years ago,” Chenal wrote.

The letter also stated that Chenal would share Stringer’s 1984 bar complaint dismissal letter with investigators, but only under a nondisclosure agreement shielding the letter from public view.

Citing public trust and transparency, the Ethics Committee declined Chenal’s request on March 20. Shope issued a subpoena forcing Stringer to turn over his letter and submit to an interview the next week.

Chenal told Yellow Sheet, a newsletter published by Arizona Capitol Times, that Stringer did not intend to comply with the subpoena for the letter. She cited her suspicion that the media would twist its words.

“There’s some information in there that could be misinterpreted, not by you, but by someone from the New Times,” she told Yellow Sheet on March 26.

Chenal did not know at the time that Kanefield’s team had already broken new ground in their investigation that would render the tussle over the bar letter irrelevant.

Resignation

Kanefield received the Baltimore police report showing Stringer’s arrest on March 25, two days before the lawmaker’s deadline to comply with the subpoena.TouchStone Global — a private security firm hired by Ballard Spahr — obtained the report through a public records request with the Baltimore Police Department and promptly emailed it to Kanefield. Baltimore Police officials had previously denied requests for the same records from media outlets, including New Times and the Arizona Republic.

Kanefield disclosed the report to Shope on the same day. Describing his reaction upon seeing its findings, Shope said, “Disbelief. Shock. On the color spectrum of emotions, it was all across the board. I was definitely not expecting that.”

Shope shared the report with Speaker Bowers, who determined that he would ask for Stringer’s resignation the following day.

The next day — March 26 — was a circus.

Chenal attempted to boot Shope from his Ethics chairmanship over a comment he made to Arizona Capitol Times on December 7. Shope had told the newspaper he believed Stringer did not “deserve” to be in the legislature over reports of his racist remarks. In a letter to Speaker Bowers, Chenal said Shope’s prior statements showed he could not be impartial in Stringer’s investigation.

The Arizona Daily Independent published a story on the same day headlined, “Major development in Stringer saga as ethics chairman could face removal.” The story was published under the “Opinion” section without a byline.

Reflecting on the attempt to oust him from his chairmanship, Shope said, “The reality is he was trying to do everything he could in order to save himself. The further away I get from it, the less upset I am about it.”

On the same day, Chenal also somehow got the idea that the House planned to expel Stringer. She filed an emergency motion for a temporary restraining order in state court shielding the 1984 letter and preventing the legislature from kicking him out. Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Rose Mroz granted a hearing on Chenal’s request for 4 p.m.

Shope, Kanefield, Ethics Committee members, and legislative staff all showed up to Mroz’s courtroom lobby on time. Confused reporters rushed to the courtroom to cover the fast-moving story. Just minutes after the hearing was scheduled to begin, a clerk walked out of Mroz’s courtroom and said it was cancelled. Neither Stringer nor Chenal were anywhere to be seen.

As it turns out, Stringer was speaking with Speaker Bowers in his office. The two had a “substantive” conversation wherein Bowers confronted Stringer with the police report’s findings, the speaker told New Times.

Bowers declined to comment on specifics of his discussion with Stringer, other than to say, “It was a hard meeting.”

Stringer submitted his resignation with a one-sentence letter: “This is to confirm my resignation as State Representative for Legislative District 1, effective 4 pm this date, March 27, 2019.”

Secret's out

Two days after Stringer stepped down, the House Ethics Committee publicly released a 426-page cache of documents gathered by Kanefield during his investigation. One of the documents stood out. The 1983 police report from Baltimore Police Detective Ed Paugh contained disturbing details that made national headlines: Patterson Park, $10, oral sex, intellectually disabled, “Mr. Dave.” Stringer once again denied that he had done anything wrong.

“Some 35 years ago when I lived in Maryland, I faced salacious allegations of sexual improprieties that had no basis in fact,” he wrote in a lengthy Facebook post published at 3 a.m.

Stringer accused “political opponents” of digging up the allegations because they disagreed with his views. He accused “the media” of treating the accusations as convictions. And he accused the legislature for engaging in a “deeply and shamefully offensive” campaign to oust him from office.

But his statement — titled “David Stringer Speaks” — did not address several open questions. He offered no insight as to how his arrest turned into child pornography charges. And Stringer did not explain why the two boys, his alleged victims, gave his name to police, as he claimed they did in his January interview with the Arizona Daily Independent.

The copy of Stringer’s criminal case history lists three victims, none of whom could be reached for comment. Kanefield’s team also did not attempt to contact either of the two victims listed in the police report. “Mr. Stringer’s resignation ended the investigation before that course of action could be explored,” said House Republican spokesperson Matt Specht.

One of the victims shares a unique name and approximate age with a man who was arrested in Baltimore on a sex offense not many years after his alleged encounters with Stringer. The man pleaded guilty, according to Maryland court records.

His charge? Causing abuse to a child.