THE FACE OF RELIGIOUS BIGOTRY

"Your neighbor Jeff Jacobsen is not all that he seems. When he's not stirring up hatred on the streets, Jacobsen is poisoning the Internet by filling it full of religious bigotry and intolerance! Jacobsen's hatred puts families at risk. Next time you see this man, recognize the face of religious bigotry."

Sherry Kinner found the leaflet in her mailbox and walked out to confront one of the men who was distributing it.

It wasn't the first time Kinner had caught people targeting Jacobsen, who lives two doors down from her. She'd spotted private investigators staking out Jacobsen's house. Her son had been questioned by a private eye, and her husband had tried, to no avail, to get the detective to say why he was keeping an eye on their neighbor.

One night when Jacobsen was out, Kinner saw two women picket his house, carrying signs denouncing Jacobsen as a bigot. They scurried away when Kinner's husband threatened to call the cops while citing, correctly, an Arizona law that prohibits picketing a private residence.

Now one of Jacobsen's enemies was leafleting her street.

"Don't ever put that trash on my mailbox again," she told the man. She says he warned her that she didn't know the entire truth about her neighbor. She replied that she knew full well why Jacobsen has been targeted.

Kinner then collected the leaflets from neighboring houses and delivered them to Jacobsen.

Jacobsen says he was grateful. He had been labeled a bigot before, but never had his detractors distributed fliers in his neighborhood.

Normally, he's picketed at his job.

If the Church of Scientology believed in a Devil, he might look a lot like Jeff Jacobsen.

His name produces a virulent reaction from the local church's leader, Reverend Leslie Durhman. "Jacobsen is in league with the worst kind of bigots--kidnapers, forcible deprogrammers, Internet terrorists who promote killing Scientologists and blowing up our churches," she tells New Times.

Scientologists have denounced Jacobsen as a bigot in picket lines at his home, at his work, and even thousands of miles away when he was visiting in Florida. A church member's Web site, meanwhile, includes Jacobsen on a list of nine of Scientology's all-time worst enemies.

The mild-mannered, single man of 43 seems hardly satanic in appearance. Tall and reserved, Jacobsen seems about as dangerous as a church mouse; it's hard to believe he's the archnemesis Scientologists make him out to be.

Jacobsen is one of the most dedicated of the church's many critics. Never a member of the religion, Jacobsen participates with other critics in an Internet debate about Scientology. And like several other hard-core local critics, he occasionally pickets the Valley's lone Church of Scientology on University Drive in Mesa as well as churches in California and Florida.

Unlike most of his cohorts, however, Jacobsen has been singled out for retaliation. And that's probably because of his role in what has become the most embarrassing debacle in the church's 45-year history.

The 1995 death of Scientologist Lisa McPherson at a church-owned hotel in Clearwater, Florida, has brought the controversial religion negative publicity like nothing before. It's also brought the church two criminal indictments.

Jacobsen's role in Scientology's disaster has never been publicized. But the church itself seems well aware of his contribution.

For his part, Jacobsen clearly enjoys being a thorn in the church's side. Despite the retaliation he's suffered, Jacobsen spends vast amounts of time researching and criticizing Scientology because, well, it's fun, he says.

"It's nonviolent. It's effective. It shows the church that it has critics and that we're not afraid. If you go to Disneyland, what happens? You take a ride and you know it's going to be safe. But if you go to Los Angeles and picket the Church of Scientology, you don't know what's going to happen. You might be followed by a private investigator. When you picket, will the Scientologists harass you, will they run away? You have to be careful. You have to plan. But it's still pretty neat," he says.

Besides organizing road trips for his fellow debunkers, Jacobsen maintains several Web sites containing hundreds of pages of information about the church and its founder, L. Ron Hubbard. To counter Scientology claims that Hubbard had a stellar college career resulting in two doctorates, Jacobsen found Hubbard's actual college records in a court file and posted them for the benefit of Internet users. The records show Hubbard actually earned a D average in two years of work at George Washington University, took a single course in nuclear physics (Hubbard later claimed to be a "nuclear physicist") and earned no degree.

What motivates Jacobsen to search through arcane records for such gems, he says, is that he objects to Scientology practices he says are harmful to its adherents. He also dislikes church policies that encourage lawsuits to harass critics, as well as efforts by the church to shut down its Internet detractors.

Scientologist attacks on Jacobsen, however, are more muddled. Signs carried by church members denouncing Jacobsen display odd messages that only make sense if you know something about Jacobsen's family and background. The church obviously knows something about that background, which explains the private investigators who showed up in Jacobsen's neighborhood and at his family's businesses in South Dakota.

As a result, Scientologists in both Phoenix and Florida blame Jacobsen for strange things. A recent issue of the National Enquirer contains a story about Scientology and two of its most famous believers, John Travolta and Kirstie Alley. An inside photo portrays a demonstration in Florida attended by Jacobsen. If you look carefully, you can see part of a sign held by a Florida picketer with a slogan Scientologists have frequently aimed at Jacobsen: "Jeff Is a Porno King."

Jacobsen says the sign refers to two things. He works for his father at Single Scene, a tame weekly for lonely Phoenicians looking for love. Jacobsen's father also owns a chain of video stores in South Dakota that stocks adult videos along with the latest releases. Scientologists have labeled Jacobsen a pornographer for those connections.

Jacobsen's "religious bigotry" is never spelled out in leaflets or picket signs; nowhere do Scientologists identify themselves on their protest materials. On a church member's Web site, meanwhile, Jacobsen's character and family business are maligned: "Like a housewife who constantly harps about her neighbors, when you open Jeff's closet, all the dirty diapers and dishpans fall out."

Ironically, Jacobsen is one of the least vitriolic of Scientology's critics. Some of the church's detractors, particularly former Scientologists, push at the limits of free speech and good taste in their attacks on the church. It's obvious some of them enjoy provoking Scientologists, who have long endured reputations for being litigious and retaliatory.

But Jacobsen is nearly as reserved in his Internet joustings with the church as he is in real life. Something of a computer nerd, Jacobsen thinks of himself as a sort of cyberspace Gandhi, preferring conscientious debate to angry name-calling.

He says he's careful not to do anything on the Internet that would get him sued, and he doesn't support other critics who violate Scientology copyrights by posting secret church materials illegally.

Despite those precautions, Jacobsen has still attained Luciferlike stature in the minds of Scientologists.

But that all started when Jacobsen, computer geek, Internet hound, noticed a police department's electronic cry for help in solving the mysterious death of a Clearwater, Florida, woman.

Scientology describes itself as the "only major new religion to emerge in the 20th century."

Founded by science-fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard, the church's seminal text is Hubbard's 1950 book Dianetics. The self-help book was described at the time of its publication as a sort of poor-man's psychoanalysis and was promoted by Hubbard as an alternative to traditional mental-health care. Through a process somewhat analogous to psychotherapy that he called auditing, Hubbard claimed that the unhappy could improve their lives by erasing the effects of traumatic memories. Hubbard called these memories engrams and said they acted like scars on the mind; only after extensive auditing and the removal of all engrams, including those left over from past lives, could a person achieve a new state of inner freedom. Hubbard said such an engram-free human being, which had never appeared on Earth before, would be known as a clear.

Hubbard's clears would be capable of amazing feats. Impervious to sickness, clears would have clairvoyant powers, perfect recall, and would be able to leave their bodies. In the summer of 1950, Hubbard announced that he had produced the world's first clear, a young woman named Sonya Bianca. But at a demonstration in Los Angeles, Bianca's supposedly perfect recall was embarrassingly underwhelming. She couldn't, for example, remember the color of Hubbard's tie after Hubbard was asked by a spectator to turn around.

Nonetheless, by 1954, Hubbard had convinced enough readers of the power of Dianetics that he organized his followers in a formal religion he called Scientology. Today, 13 years after Hubbard's death, the church claims a worldwide membership of eight million. Critics say the real extent of the church is far smaller. The Mesa church claims a statewide membership of 1,000, and Reverend Durhman says that about 200 members attend church events.

New church members work toward becoming clears by attending increasingly expensive classes and auditing sessions. A church magazine encourages members to make pilgrimages to a church center in Los Angeles to complete their journey across "the Bridge" to become clears. Critics estimate the total cost of that journey to be about $100,000 to $200,000. Once a clear, a Scientologist is also known as an operating thetan, or OT, referring to the ability to communicate with his or her inner thetan, an entity somewhat analogous to a soul. Members then continue their spiritual journey, moving to levels such as OT II and OT III and up to OT VIII, the highest current level attainable. John Travolta is reportedly an OT V.

It's only at OT III--a step that alone costs more than $8,000, according to a recent church price list--that a believer is told the true nature of the thetan inside him or her.

According to materials made public in a lawsuit brought by a former believer, Scientologists who reach OT III are told that thetans are space aliens exiled to Earth 75 million years ago by Xenu, an evil galactic overlord.

Numerous ex-members have confirmed the authenticity of the OT III materials from the lawsuit, but the church has never officially acknowledged that Xenu is, in fact, a key figure in its theology.

Hubbard himself wrote that the OT III materials sometimes proved too much of a shock for his believers, and he emphasized that they not be revealed to a pilgrim too soon.

Critics point to such writings and charge that Scientology is more a money-making scheme than a religion. What other church asks its believers to pay such huge sums to find out what the church is about? they ask.

Increasingly, outside observers have asked the same question. In 1991, Time deemed Scientology a "ruthless global scam"--on its cover. The church responded with a $415 million lawsuit against the magazine. Eventually, a federal judge dismissed all but one of Scientology's claims of libelous statements.

Two years after the Time story, a new forum for discussions about the church emerged: a newsgroup on the burgeoning Internet. Called alt.religion.scientology, or a.r.s for short, the newsgroup rapidly became one of the busiest in cyberspace. If Scientology operated by holding back information from its members, the Internet provided a way for the church's critics to make those secret teachings available instantaneously and all over the world. Pro-Scientology retaliations to postings on a.r.s--in the form of illegal message cancellations--eventually brought the newsgroup to the attention of computer geeks with no interest in the Scientology debate. Someone was canceling a.r.s postings critical of the church, a violation of federal law, and Internet sleuths tried, with little luck, to identify who was pushing the delete button. When a Scientology lawyer tried to have the entire newsgroup removed, the battle over a.r.s became for many computer enthusiasts a struggle for free speech in general.

The church sought help from the federal government to combat the posting of its secret, copyrighted teachings--teachings that critics argued had been made part of the public domain through numerous court filings. Armed with federal warrants, church officials raided the homes of several computer critics they believed were behind publication of OT materials. Computer enthusiasts, meanwhile, howled in protest.

And some of them, including an Arizona contributor to a.r.s named Jeff Jacobsen, began to picket churches of Scientology.

For Jacobsen, the Internet gave him an outlet for his most abiding passion: his interest in cultish new religions.

Since 1984, Jacobsen has helped his father and sister publish Single Scene. He also runs Friday-night dances sponsored by the paper at several Valley resorts.

But Jacobsen's real interests lie in what he believes are churches that wield undue influence over their members.

He says he belonged to such a church as a young man, a strict Christian sect in South Dakota. Jacobsen now calls that particular United Pentecostal Church a cult, and says that for six years he lived like a slave for the demanding religion.

Today, he says he belongs to a more open Christian church, but his experience left him with a curiosity about other cultish organizations.

For years, nearly all of his attention has been devoted to a single church--Hubbard's Church of Scientology.

"The more contact I had with Scientology, the more I could see it was much more dangerous than the group I was involved in," he says. Jacobsen began a methodical study of the religion in 1987, and has collected hundreds of volumes of the writings of L. Ron Hubbard. He also regularly participates in the debate on a.r.s, and has helped coordinate national pickets of Scientology churches with other members of the newsgroup.

In March 1996, Jacobsen and 17 other critics traveled to Clearwater, Florida, the church's spiritual headquarters. Jacobsen and the others spent a day of uneventful picketing outside a church-owned bank and then returned home.

Six months later, Jacobsen says, he started thinking about rallying the troops for another trip to Clearwater, but this time he decided they should target one of Scientology's holiest sites, the Fort Harrison Hotel. According to a church brochure, the hotel is a religious retreat where Scientologists come "from around the world to participate in advanced auditing and training."

Before organizing the trip, Jacobsen surfed the Internet for information on Clearwater, and landed on the city's home page. Clicking his way to the police department's site, Jacobsen noticed that homicide detectives were asking for the public's help in solving the "suspicious death" of a woman named Lisa McPherson. The notice asked anyone who had information about McPherson to contact the police. It also included McPherson's last known address.

Jacobsen realized, to his surprise, that he recognized that address. It was the same street number as the Fort Harrison Hotel, the Scientology mecca Jacobsen had planned on picketing. Although the police notice made no mention of either the hotel or Scientology, Jacobsen suspected that McPherson's "suspicious death" might involve the church itself. He typed up a brief mention of McPherson in a newsletter he sends to other church critics, and mailed a copy to Tampa Tribune reporter Cheryl Waldrip.

Jacobsen says Waldrip did nothing with his tip until she realized that no obituary or any other information about McPherson's death had appeared in print. That made her suspicious, Jacobsen says, and led her to look into the police investigation.

Articles in the Tribune and other papers, and the church's changing story about what happened in McPherson's death, soon led to national coverage. Newspapers questioned Scientology practices and printed accusations that adherents, like McPherson, are held against their will. The attention turned an obscure death investigation into a highly publicized battle between police and Scientology. Eventually, the church was indicted for abuse of a disabled adult and unauthorized practice of medicine, both felonies. McPherson's family, meanwhile, has filed a civil lawsuit against the church.

The death of Lisa McPherson has become the most publicized controversy in the church's 45-year history. Stories about McPherson have appeared in nearly every major American newspaper as well as foreign publications and on numerous television programs.

Jacobsen, meanwhile, maintains an extensive archive of information about the case on several Web sites and, through the help of other a.r.s members, in four foreign languages.

McPherson was a 36-year-old member of the church who had belonged to the religion for 13 years. In November 1995, McPherson had finally crossed the Bridge to become a clear. But she told friends and family that she was unhappy at her job at a Scientology-owned publisher and that she planned to leave it and return home to Dallas.

On November 18, McPherson was involved in a minor auto accident. When paramedics arrived, they found that McPherson, who appeared unhurt, had disrobed. "I need help. I need to talk to someone," she told them. Paramedics noted McPherson said she had been doing "wrong things she didn't know were wrong."

McPherson was taken to a hospital, where a doctor recommended that she go through a psychiatric evaluation. Scientologist friends of McPherson arrived, however, and objected, saying that psychiatric evaluations are forbidden in their religion.

With Scientologists at her bedside, McPherson told hospital workers that she wanted to go home with her friends. A doctor advised against it, but ultimately released McPherson, noting that the Scientologists promised they would provide 24-hour care for the troubled woman.

McPherson checked into the Fort Harrison Hotel for, the church said, rest and relaxation. Seventeen days later, she was rushed in a Scientology van to a hospital 24 miles away, bypassing four closer hospitals in order to get to a Scientologist doctor. McPherson was dead by the time she got there.

An autopsy performed by the county medical examiner found that McPherson had died from a blood clot brought on by "bed rest and severe dehydration," according to the examiner's report. McPherson hadn't had anything to drink for five to 10 days and was unconscious for one or two days before her death, said the medical examiner, who added that McPherson's arms were covered with what appeared to be cockroach bites. The autopsy also found evidence of a staph infection, and the church argues that it was the infection, which came on suddenly, that caused the clot and killed McPherson. Church officials insisted that McPherson's time at the hotel had been pleasant and that she had exhibited no medical problems until her final day.

But the church's own records, released on a judge's orders, show that McPherson's mental and physical condition plummeted during her stay. Notes kept by the hotel's health-care staff show that she was violent, incoherent, and seemed unable to care for herself. Other notes indicate that McPherson had tried to leave the hotel, and that she had hallucinated that she was L. Ron Hubbard.

As details of the McPherson case gradually emerged, Jacobsen and other Scientology critics began telling reporters that McPherson had been subject to a Hubbard technique called the "introspection rundown."

In a 1974 technical manual, Hubbard wrote that a person "in a psychotic break" should be isolated. "No one speaks to the person or in his hearing," Hubbard instructed. The subject under introspection rundown could not be released until he could provide, in writing, persuasive evidence that he had reformed. If not, he should be told: "Dear Joe. I'm sorry but no go on coming out of isolation yet."

Jacobsen says the introspection rundown is simply a Scientology policy of holding people against their will. Although the church insists that McPherson was cared for in a posh hotel environment, Jacobsen points to the insect bites on her arms and suggests that McPherson was held, forcibly, in a hotel basement. Several former church members have claimed that the same thing happened to them. One former member, Stacy Young, told the St. Petersburg Times she had been ordered to guard a woman who was kept for two months in isolation during introspection rundown in a dirt-floor shack east of Los Angeles. Scientology officials say Young and the others are lying.

Each new development in the case is watched carefully by Jacobsen and other critics. Scientologists, meanwhile, complain that Jacobsen has no real interest in McPherson and instead cruelly exploits her death for his own purposes of criticizing their religion.

When Jacobsen pickets Scientology churches, he carries a sign with a photograph of McPherson and the years of her birth and death.

"She, to us, represents all of the other people who have been hurt by Scientology," Jacobsen says. "Why did people wear bracelets for soldiers lost in Vietnam? They didn't know those soldiers. How could you care about somebody you don't know? You do. You just do."

"We are not the first church he's attacked, and doubt we'll be the last one," says Reverend Durhman, who leads the Mesa congregation. "In fact, he has made attacking churches a lifelong career.

"You have to ask yourself what would motivate someone to spend their time at such a vicious activity. We want him to go away and stop harming people of goodwill."

Durhman blames Jacobsen and other demonstrators for an environment that encourages vandalism of their church. "There was some graffiti, and some property was damaged. Some benches in the back were thrown into the canal," she says.

She acknowledges that church members have been picketing and leafleting Jacobsen's work and home. "It's the parishioners that are concerned about this and want to get out the truth about him," she says.

She dismisses Jacobsen's complaints about retaliation against Internet critics and about Scientology's withholding of information from adherents.

"It isn't that this stuff is weird or sinister or hidden or whatever. It's just that it's understood that when you have a good body of theology, you don't just dump the whole thing on somebody at the beginning," Durhman says.

She herself has not attained the level of OT III, and so she could not comment on the revelations about Xenu the galactic overlord. Durhman did object to the dissemination of such materials over computer networks.

"Well, of course we don't want it for free on the Internet. Don't you understand that? It's copyrighted material. It belongs to parishioners when they are at that level of spiritual attainment. We have the right to receive donations for all of our services. So it's not right for people to criticize us for how we operate," Durhman says.

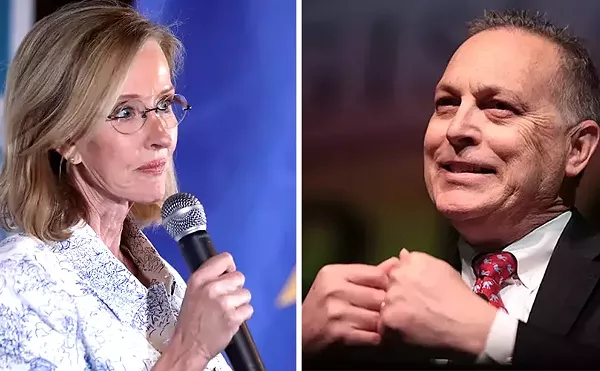

One of Durhman's parishioners who has picketed Jacobsen is also a familiar local personality. Realtor Russell Shaw, whose advertisements frequently run on radio and television, maintains a Web site denouncing Jacobsen as an "A.R.S. Bigot."

Shaw couldn't be reached for comment on his Web site. His wife, Wendy, says that he is in Los Angeles and could not be contacted.

But Shaw's Web site makes clear his feelings about Jacobsen. Comparing Jacobsen and eight other critics to Adolf Hitler and Ku Klux Klan members, Shaw writes that Jacobsen's "always disparaging comments have the effect of creating violence, discrimination and hatred. . . . When you open Jeff's closet, all the dirty diapers and dishpans fall out."

Shaw criticizes Jacobsen for "aligning himself" with other critics who have criminal records. (One, for example, local deprogrammer and Scientology critic Rick Ross, pulled off a 1971 jewelry heist in his early 20s and was put on probation, a decade before he began counseling members of authoritarian religions.)

Shaw also castigates Jacobsen because his father was convicted of tax evasion in South Dakota. "Jeff works for his father and surely must be aware of the tax avoidance schemes going on in the business."

Jacobsen explains that South Dakota recently passed a new law that taxes newspaper distribution. His father objected to it as an unconstitutional infringement of free speech, and refused to pay it. "He lost in court, paid a $1,000 fine, and spent a day in jail," Jacobsen says.

Shaw also criticizes Jacobsen because his father's South Dakota video chain rents adult films, and Shaw takes a swipe at the family business: "They make a living providing advice to 'singles' on how to make relationships work. Surprisingly, Jeff and his sister have not been able to make relationships work for themselves and are both approaching middle age single."

Jacobsen says he considers the site "goofy," and only objects to Shaw's statements about his father. "My father's not involved. And he's distorting the facts about my dad. To get at me, Shaw attacks my family," Jacobsen says. "That's Shaw's only Web page. It doesn't promote his business. It's for nothing but to denigrate critics of his church with smear campaigns," he says.

Besides his Web barrage, Shaw has also targeted Jacobsen by picketing one of his Friday-night dances.

Jacobsen plays music at the weekly events, held at resorts such as Mountain Shadows in Paradise Valley, where readers of Single Scene gather. Four times, Scientologist picketers have demonstrated outside, carrying signs with slogans like "Jeff Is a Bigot," "Jeff Is a Porno King," and "Say No to Religious Hatred."

On two of those occasions, Jacobsen says, the picketing occurred on a darkened sidewalk where no hotel workers or guests could see what was going on. He says he wouldn't even have known he was being picketed if a friend hadn't come in and told him.

Jacobsen's protesting of the Mesa church is far more visible.

On a recent afternoon, Jacobsen and four other church critics carry signs outside the church. Rush-hour traffic whizzes by in a loud roar punctuated by frequent honks.

Kristi Wachter walks with a sign hanging around her neck. It reads: "UFO Cult."

Wachter is an a.r.s devotee from San Francisco who dropped by to picket while traveling through Phoenix. She says since she began protesting against the church, Scientologists have frequently retaliated by showing up outside her California home, where private residences can legally be picketed.

Bruce Pettycrew, meanwhile, hefts a sign that reads "Scientology Kills." It refers to Lisa McPherson, he says, but Jacobsen adds that the slogan is also meant to counter a sign Scientologists frequently carry that reads "Psychiatry Kills."

Pettycrew is a Phoenix software engineer who began picketing the church after Internet users were raided by church officials. He estimates that he demonstrates more than once a week, and last year he was sued by the local church for his frequent protests. The lawsuits have been dropped, but Pettycrew says he's still under a court order not to cause noise that can be heard in the church.

Pettycrew says he's motivated to expose Scientology because of its secretive nature. "The world has a problem with pseudoscience. I feel Scientology's one of the grossest examples of that, and I think it's a good place to press the attack," he says.

Pettycrew says out-of-town a.r.s devotees set up pickets about twice a month. Jacobsen, meanwhile, tries to go to Los Angeles and Clearwater for road-pickets several times a year. On December 5, the anniversary of Lisa McPherson's death, Jacobsen helped organize a vigil in Clearwater that drew 100 people.

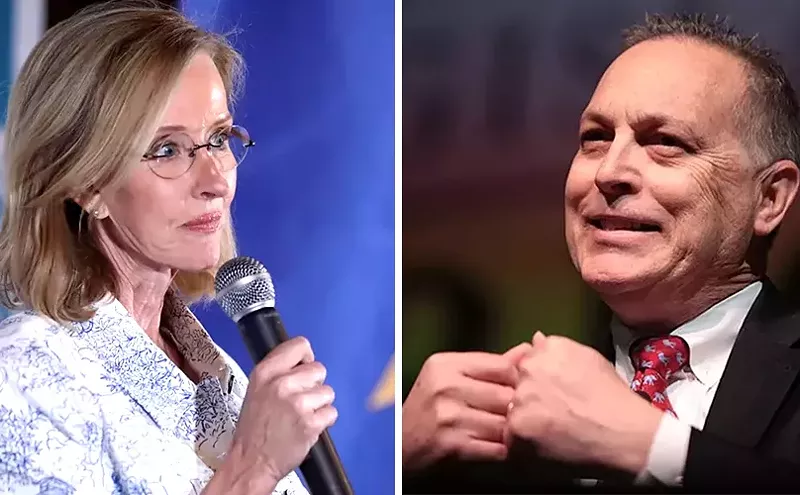

Inside the Mesa church, Reverend Durhman and others keep an eye on the demonstration. Durhman comes outside to greet a visitor and to allow her picture to be taken.

Later, in a telephone interview, she says, "Jacobsen and his picketer pals are the ones harassing our church and spreading lies about us. What he does to our religion is no different than someone painting a swastika on a synagogue or burning a cross in a black family's yard--no different whatsoever."